The “Double Whammy”: When antidepressant resistance meets autoimmunity

Published in Healthcare & Nursing

It is well-established that the presence of chronic somatic disorders is a risk factor for developing depressive symptoms, due in part to the way patients perceive their deteriorating health conditions and/or the financial burden arising from treatments and productivity losses. Given the multifactorial disease nature, could depression in turn also elevate the risk for subsequent chronic somatic disorders?

Let us study autoimmune diseases as an example. Studies to date suggested an “inflammation theory” underlying depression pathogenesis – depression and inflammation often interact with each other via cytokine balance, and that a bidirectional crosstalk between the endocrine and immune systems is possible1,2. Depressed individuals often had elevated levels of immune activation and pro-inflammatory markers, with 1.3- to 2.5-fold higher risk of developing autoimmune diseases compared with healthy controls3-8. It is possible to explain the linkage in view of the biological mechanism, by which chronic stress may have disturbed signaling pathways in the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. As the pathways are also involved in the regulation of immune functioning via cytokine activities, sustained stimulation with depressive symptoms may dysregulate the immune system and subsequently lead to autoimmunity9-11.

Antidepressants, coincidentally, appear to possess anti-inflammatory property apart from its effect in monoamine regulation for depressive symptom improvement12. If the inflammation theory holds for the pathogenesis mechanism of depression, could the therapeutic effects of antidepressants be attributed also to its anti-inflammatory feature? Additionally, it has been speculated that patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), who are typically hard-to-treat due to non-responsiveness to antidepressants, could suffer from a more dysregulated inflammatory process and a greater risk of autoimmune diseases because of the reduced benefits from antidepressants13,14. Evidence supporting a positive association between TRD and autoimmunity is available, but mostly unable to tell whether autoimmune conditions occur before or after the exposure. The temporality of events, however, is crucial to support the inflammatory theory – Meanwhile, the “TRD phenomenon” could also be the consequence of an insufficient understanding in the pathogenesis of depression, such that current treatment modalities may have inadequately addressed the disease with proper targets.

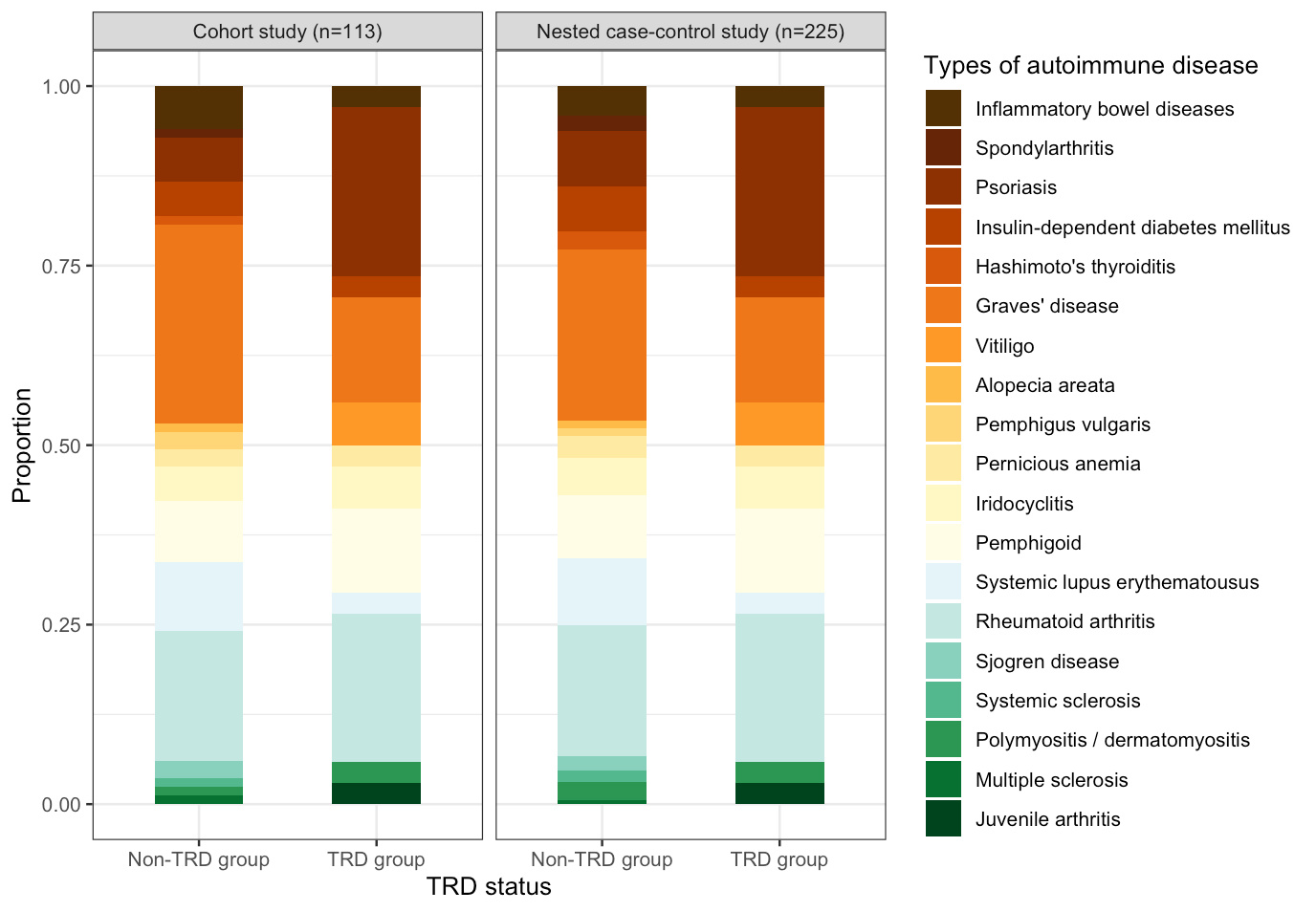

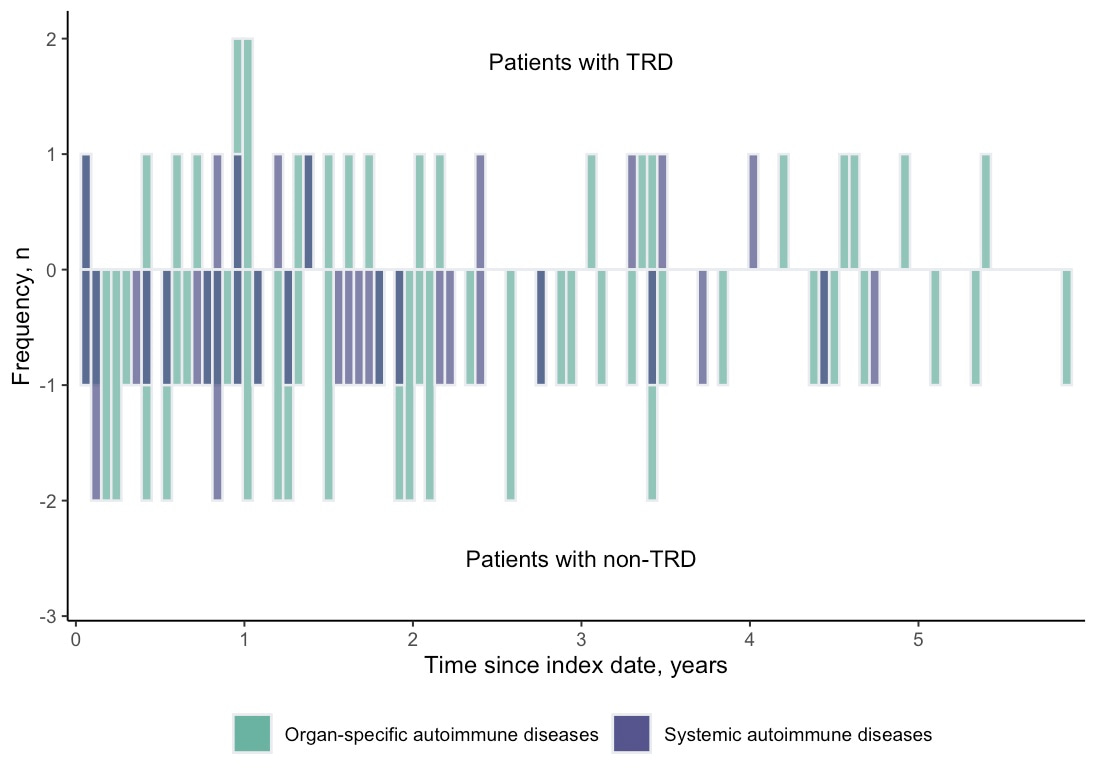

Intrigued by the knowledge gap and limitations of current studies, we therefore designed a cohort study and a nested case-control study in parallel to test the association between TRD and risk of subsequent autoimmune diseases with consideration of the temporality issue. Using the territory-wide electronic medical records in Hong Kong, we identified patients with incident depression between 2014 and 2016 without autoimmune history and followed up from diagnosis to death or the end of 2020 to ascertain the TRD status and compare the post-TRD autoimmune incidence. We found that the cumulative pooled incidence of 22 types of autoimmune diseases among the patients with TRD was generally higher than the non-TRD (21.5 vs 14.4 per 10,000 person-years). Nested case-control analysis showed a significant association (OR: 1.67, 95%CI: 1.10–2.53) between TRD status and autoimmune diseases, whilst the cohort study suggested a marginally significant association (HR:1.48, 95%CI: 0.99–2.24). The most frequently developed types of autoimmune diseases were Graves’ disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis (Figure 1). 75% of autoimmune diseases occurred within three years after antidepressant resistance with mean onset time of approximately 2 years (Figure 2). The findings have been recently published in Translational Psychiatry.

Figure 1. Frequency of occurrence of individual autoimmune diseases during follow-up

Figure 2. Onset distribution of autoimmune diseases in the cohort study

In Epidemiology, “triangulation” is a common practice to increase the reliability of answers by integrating results from alternative study approaches, so that we could preserve the advantages and complement the limitations of each study design. In our study, the results from both study designs pointed towards the same conclusion with a similar risk magnitude, which strengthens the reliability of results. It seems that our findings are in line with the suggested inflammation theory – Studies documented that patients with depression had increased proinflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which were also manifested in the cytokine profiles of patients with organ-specific and/or systemic autoimmune diseases,4,15-17. Introduction of proinflammatory agents, such as interferon-alpha (IFN-α), in turn induces mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms, whilst the use of antidepressants was associated with decreased proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α, among responders3,18,19. As a result, the lack of antidepressant response may logically predispose the non-responders, who are less likely benefited by the anti-inflammatory effect of antidepressants, to a higher chance of a more dysregulated inflammation and cytokine dynamics. On the other hand, it was also possible that patients with heightened baseline proinflammatory cytokine release may be predisposed with both antidepressant resistance and autoimmunity, whilst hard-to-treat depression happened to manifest before the development of autoimmune diseases. In either way, nevertheless, chronic inflammation seems to play an important role in the development of both antidepressant resistance and autoimmunity.

Taken together, whilst it is upsetting to find patients could suffer from the “Double Whammy” of treatment resistance and risk of another chronic disease, the findings reported herein shed light on the understanding and management of hard-to-treat depression. We added evidence to support the involvement of inflammation in the pathogenesis of depression and treatment resistance, which may stimulate interests to explore the use of anti-inflammatory agents and cytokine inhibitors as new antidepressants, or as adjunct to current antidepressants, for patients without satisfactory treatment responses. Further studies will be helpful to determine whether drugs for autoimmune diseases should be pharmacologically repurposed for depression and reduce the use of antidepressants. As for the patients with TRD, clinical awareness should be raised to manage treatment refractoriness early and detect subsequent comorbidities, followed by timely intervention to prevent disease progression. It is also worthy to investigate further if multidisciplinary care would be helpful to manage the joint burden arising from multifaceted mental and somatic consequences.

References

- Bica T, Castello R, Toussaint LL, Monteso-Curto P. Depression as a Risk Factor of Organic Diseases:An International Integrative Review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2017;49(4):389-399.

- Monteso Curto MP, Martinez Quintana MV. [Co-morbility during depression]. Rev Enferm. 2009;32(12):36-39.

- Kohler O, Krogh J, Mors O, Benros ME. Inflammation in Depression and the Potential for Anti-Inflammatory Treatment. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(7):732-742.

- Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):446-457.

- Andersson NW, Gustafsson LN, Okkels N, Taha F, Cole SW, Munk-Jorgensen P, et al. Depression and the risk of autoimmune disease: a nationally representative, prospective longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2015;45(16):3559-3569.

- Roberts AL, Kubzansky LD, Malspeis S, Feldman CH, Costenbader KH. Association of Depression With Risk of Incident Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Women Assessed Across 2 Decades. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(12):1225-1233.

- Frolkis AD, Vallerand IA, Shaheen AA, Lowerison MW, Swain MG, Barnabe C, et al. Depression increases the risk of inflammatory bowel disease, which may be mitigated by the use of antidepressants in the treatment of depression. 2019;68(9):1606-1612.

- Sparks JA, Malspeis S, Hahn J, Wang J, Roberts AL, Kubzansky LD, et al. Depression and Subsequent Risk for Incident Rheumatoid Arthritis Among Women. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73(1):78-89.

- Smith SM, Vale WW. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):383-395.

- Elenkov IJ, Iezzoni DG, Daly A, Harris AG, Chrousos GP. Cytokine dysregulation, inflammation and well-being. 2005;12(5):255-269.

- Black PH. Stress and the inflammatory response: a review of neurogenic inflammation. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16(6):622-653.

- Nazimek K, Strobel S, Bryniarski P, Kozlowski M, Filipczak-Bryniarska I, Bryniarski K. The role of macrophages in anti-inflammatory activity of antidepressant drugs. 2017;222(6):823-830.

- Chamberlain SR, Cavanagh J, de Boer P, Mondelli V, Jones DNC, Drevets WC, et al. Treatment-resistant depression and peripheral C-reactive protein. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;214(1):11-19.

- Gasparini A, Callegari C, Lucca G, Bellini A, Caselli I, Ielmini M. Inflammatory Biomarker and Response to Antidepressant in Major Depressive Disorder: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2022;52(1):36-52.

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Worthman C, Angold A, Costello EJ. Cumulative depression episodes predict later C-reactive protein levels: a prospective analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(1):15-21.

- Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):230-239.

- Barak V, Shoenfeld Y. Cytokines in Autoimmunity. In: Shoenfeld Y, ed. The Decade of Autoimmunity. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.; 1999:313-322.

- Strawbridge R, Arnone D, Danese A, Papadopoulos A, Herane Vives A, Cleare AJ. Inflammation and clinical response to treatment in depression: A meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(10):1532-1543.

- Liu JJ, Wei YB, Strawbridge R, Bao Y, Chang S, Shi L, et al. Peripheral cytokine levels and response to antidepressant treatment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(2):339-350.

Follow the Topic

-

Translational Psychiatry

This journal focuses on papers that directly study psychiatric disorders and bring new discovery into clinical practice.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Moving towards mechanism, causality and novel therapeutic interventions in translational psychiatry: focus on the microbiome-gut-brain axis

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 19, 2026

From mechanism to intervention: translational psychiatry of childhood maltreatment

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in