The Hidden Threat Beneath Our Feet: How Microplastics Are Silently Transforming Soil and Our Food System

Published in Earth & Environment and Agricultural & Food Science

Imagine this: A teaspoon of soil from your backyard contains more than just dirt, water, and worms. It might also contain hundreds, even thousands, of tiny plastic particles – microplastics. These fragments, smaller than a sesame seed, are an invisible pollutant infiltrating the very foundation of our terrestrial ecosystems: the soil. A recent comprehensive review published in the International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology synthesizes overwhelming evidence showing how microplastics are altering soil health, disrupting life within it, and potentially entering the food we eat.

What Are Microplastics and How Do They Get Into Soil?

Microplastics (MPs) are plastic pieces less than 5 mm in size. They come in various forms:

-

Primary MPs: Intentionally manufactured small plastics (e.g., microbeads in cosmetics, synthetic fibers from clothing).

-

Secondary MPs: Result from the breakdown of larger plastic items (bags, bottles, packaging).

-

Nanoplastics (NPs): Even smaller particles (1-100 nm), posing potentially greater risks.

Soil is a major sink for plastics, potentially receiving 4-23 times more plastic pollution than oceans. Sources are diverse and often unintentional:

-

Agricultural Practices: Plastic mulch films (used widely for weed control, moisture retention, and warming soil) fragment over time. Studies show mulched soil can contain *over 5,000 particles/kg* compared to non-mulched soil (~260 particles/kg). Concentration increases with years of use (e.g., 80 particles/kg after 5 years, 1,075 particles/kg after 24 years in cotton fields).

-

Sewage Sludge/Biosolids: Wastewater treatment plants capture up to 90% of MPs from sewage. This sludge, rich in nutrients, is often applied to agricultural land as fertilizer, injecting thousands of plastic particles per kilogram into the soil.

-

Compost: Contaminated food waste and biodegradable plastics (which often don't fully degrade) can introduce MPs into compost used on gardens and farms.

-

Irrigation: Using water from contaminated rivers or lakes carries MPs into fields.

-

Atmospheric Deposition: Tiny plastic fibers and fragments from tires, industrial emissions, and urban dust settle onto land, even in remote areas.

-

Flooding: Floodwaters deposit plastic debris onto floodplain soils.

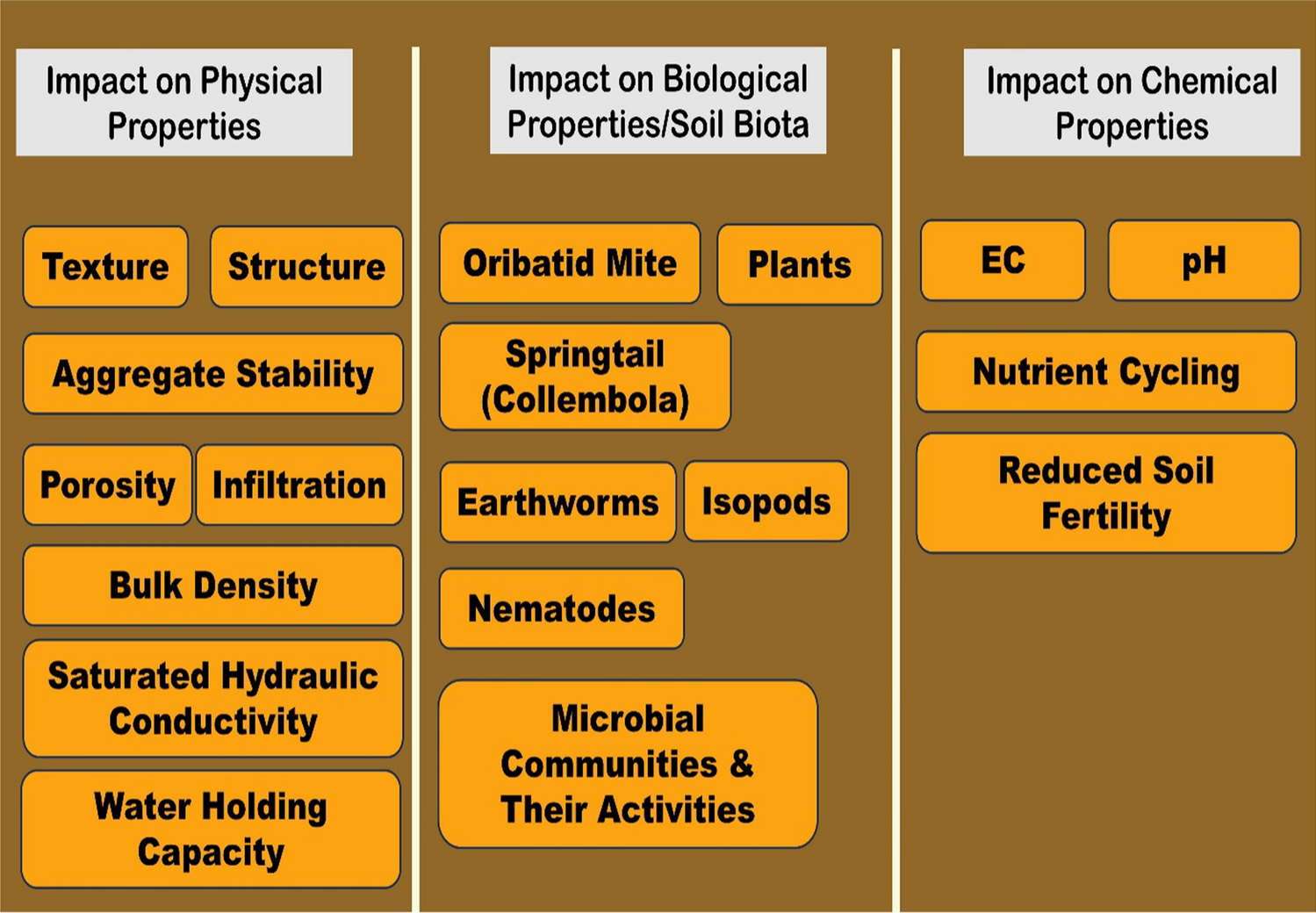

How Microplastics Alter the Physical "Architecture" of Soil

Soil is a complex structure, like a intricate city for microbes and roots. Microplastics act as disruptive invaders:

-

Water Movement: MPs change how water moves and is stored.

-

They can reduce water holding capacity (WHC), making soil drier and less able to sustain plants, especially in clay soils. Imagine plastic fragments blocking the tiny pores that hold water.

-

They can alter water infiltration (rainwater soaking in). Small particles might clog pores, slowing infiltration, while larger fibers might create channels, sometimes speeding it up initially but increasing evaporation later.

-

They can increase water repellency (hydrophobicity), causing water to bead up and run off instead of soaking in.

-

-

Density and Structure: Adding low-density plastics generally reduces soil bulk density. While this might seem good for root growth (like loosening compacted soil), it often creates unstable "ineffective pores" filled with air instead of water. MPs, especially fibers, can disrupt soil aggregates – the natural clumps of soil particles bound together. These aggregates are crucial for water retention, root growth, and preventing erosion.

-

Cracking and Contaminant Movement: Larger MPs (5-10 mm) make soil more prone to desiccation cracking as it dries. These cracks become express lanes for water evaporation from deep layers and for MPs and other pollutants (like pesticides or heavy metals) to move deeper into the soil profile.

How Microplastics Disrupt Soil Chemistry and Nutrient Cycling

Soil chemistry is a delicate balance maintained by countless chemical reactions and microbial processes. MPs throw wrenches into this system:

-

pH and Conductivity: MPs can subtly alter soil pH (acidity/alkalinity) and electrical conductivity (EC), depending on the plastic type and the original soil properties. Even small changes can affect nutrient availability.

-

Nutrient Cycling Under Siege: This is perhaps the most significant impact. Microbes and enzymes are the engines driving the breakdown of organic matter and the release of nutrients (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium, etc.) for plants.

-

MPs alter the activity of key enzymes involved in nutrient cycles (e.g., urease, phosphatase, dehydrogenase). Effects are highly variable – some MPs increase activity, others decrease it, depending on the plastic type, concentration, and soil conditions (See Table 2 in the paper).

-

They affect the abundance and function of microbes responsible for processes like nitrogen fixation, nitrification (converting ammonium to nitrate), and denitrification (converting nitrate to gas). Some studies show MPs can increase emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), a potent greenhouse gas.

-

They change the dynamics of dissolved organic matter (DOM), a crucial pool of carbon and nutrients. MPs, especially polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE), can significantly increase DOM concentrations.

-

-

Toxic Hitchhikers: MPs act like sponges for other pollutants. They can adsorb heavy metals (like Cadmium, Lead, Zinc), pesticides, antibiotics, and other harmful chemicals from the soil solution. While this might temporarily reduce plant uptake, it concentrates these toxins and can increase exposure to soil organisms. MPs can also transport these adsorbed pollutants deeper into the soil or into organisms that ingest them (like earthworms).

-

Carbon Conundrum: Plastics are carbon-based. While the inert carbon in MPs might serve as a long-term carbon pool, it can also alter the soil's carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio, potentially leading to microbial nitrogen immobilization (microbes "lock up" nitrogen, making it unavailable to plants).

The Silent Suffering of Soil Life (Biota)

Soil is teeming with life – bacteria, fungi, earthworms, springtails, mites, nematodes – all playing vital roles in decomposition, nutrient cycling, soil structuring, and plant health. MPs are a significant stressor:

-

Microbial Shifts: MPs alter the diversity, composition, and function of bacterial and fungal communities (See Tables 3, 4 & 5 in the paper). Certain bacterial groups (e.g., Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria) often increase, while others decrease. The balance shifts, potentially disrupting essential ecosystem services. Fungal communities, including vital mycorrhizal fungi (which form symbiotic partnerships with plant roots), are also affected.

-

Earthworm Impacts: Earthworms are ecosystem engineers. They ingest soil, breaking down organic matter and creating channels for air and water. Studies show:

-

They readily ingest MPs, which can be found in their casts (excrement) and even concentrated in predators (like chickens) that eat them – introducing MPs into terrestrial food chains.

-

MPs can cause physical damage (skin lesions), reduce growth rates, increase mortality (especially at high concentrations >7%), impair reproduction, and cause oxidative stress and immune system damage in species like Lumbricus terrestris and Eisenia fetida.

-

They transport MPs vertically through the soil profile via their burrowing and casting activities.

-

-

Springtails and Mites: These tiny arthropods are crucial decomposers. MPs can reduce their mobility, reproduction, and growth. They also actively transport MPs through the soil.

-

Nematodes: Microscopic worms essential for nutrient cycling. MPs can be ingested by nematodes, affecting their survival, reproduction, and behavior. Larger particles seem more harmful than smaller ones.

-

The Plastisphere: MPs create new, artificial surfaces in the soil that specific microbes colonize, forming a unique ecosystem called the "plastisphere." This community differs from the surrounding soil and may include potential pathogens or microbes adapted to degrade plastics (a potential silver lining, but not well understood yet).

Plants: Uptake, Stress, and Reduced Harvests

Perhaps most alarming is the evidence that plants can interact with, and even absorb, microplastics:

-

Uptake Pathways: While the full mechanisms are still being unraveled, potential routes include:

-

Crack Entry: MPs entering root tissues at points where lateral roots emerge or through damaged areas.

-

Apoplastic Transport: MPs moving through the spaces between root cells, potentially driven by water flow (transpiration pull). The Casparian strip in the endodermis is a barrier, but it can be bypassed during development or at root junctions.

-

Endocytosis: Cells engulfing very small NPs (though less common for larger MPs).

-

-

Effects on Plant Health:

-

Germination & Growth: Many studies report reduced seed germination rates (e.g., cress, sorghum, blackgram, soybean) and inhibited root and shoot growth (e.g., broad bean, rice, mung bean, wheat). Effects depend heavily on plastic type, size, concentration, and plant species.

-

Biomass Reduction: Shoots, roots, and fruit biomass can be significantly reduced (e.g., tomato, lettuce, common bean, maize).

-

Nutrient & Water Uptake: MPs adhering to roots or blocking pores can physically hinder the uptake of water and essential nutrients.

-

Oxidative Stress: MPs, especially nanoplastics, can induce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), damaging plant cells. Plants respond by activating antioxidant defenses (e.g., SOD, CAT enzymes), but this diverts energy from growth.

-

Photosynthesis Disruption: Reduced chlorophyll content and impaired photosynthetic efficiency are common observations (e.g., lettuce, cucumber, maize).

-

Metabolic Changes: MPs alter metabolic pathways in plants, affecting energy production, amino acid synthesis, and cell wall composition.

-

Heavy Metal Interaction: MPs can adsorb heavy metals in soil. Sometimes this reduces plant uptake of the metal (reducing toxicity), but sometimes MPs loaded with metals can increase plant exposure. Co-contamination often has more severe effects.

-

A Call for Understanding and Action

The evidence is clear: microplastics are a pervasive and multifaceted threat to soil ecosystems. They alter the physical foundation, disrupt the delicate chemical balances, harm the diverse biological communities, and negatively impact plant growth and potentially food safety. Key messages from the review:

-

Ubiquity & Severity: MPs are found in soils worldwide at concerning concentrations (see the extensive Table 1 in the paper), directly linked to human activities (agriculture, waste disposal).

-

Complex Interactions: The effects are not simple or uniform. They depend on the type (PET, PE, PS, fibers, fragments, etc.), size (micro vs. nano), shape, concentration of MPs, and the specific soil properties (texture, pH, organic matter) and environmental conditions.

-

Soil Biota Under Threat: The essential workers of the soil – microbes, earthworms, arthropods – suffer physiological damage, behavioral changes, and population shifts under MP stress, disrupting critical ecosystem functions.

-

Plants Are Not Immune: Plants uptake MPs, experience physiological stress, show reduced growth and yield, and potentially introduce plastics into the food chain.

-

Knowledge Gaps Remain: The long-term effects, the behavior of nanoplastics, the full implications for food safety, and effective remediation strategies urgently need more research. The impact of additives (like phthalates) leaching from plastics also requires more attention.

-

Standardization Needed: Developing standardized methods for extracting, identifying, and quantifying MPs in complex soil matrices is crucial for comparing studies and monitoring trends.

The Way Forward: Addressing microplastic pollution in soil requires a multi-pronged approach:

-

Source Reduction: Drastically reducing plastic use, especially single-use plastics and promoting truly biodegradable alternatives for agriculture.

-

Improved Waste Management: Preventing plastic leakage into the environment, enhancing wastewater and sewage sludge treatment to capture MPs, and developing safer sludge disposal/use strategies.

-

Sustainable Agriculture: Exploring alternatives to plastic mulch (e.g., biodegradable films that actually degrade, paper mulches), reducing reliance on sewage sludge compost, and implementing soil conservation practices.

-

Continued Research: Focusing on long-term impacts, nanoplastics, food chain transfer, microbial degradation potential, and remediation techniques.

-

Policy and Regulation: Developing policies to limit primary MP use, regulate sludge application, and promote circular economy principles for plastics.

Our soil is not just dirt; it's a living, breathing foundation of life on land. Protecting it from the pervasive and insidious threat of microplastics is essential for sustaining agriculture, biodiversity, and ultimately, our own health.

References:

Hanif, M.N., Ajjaz, N., Azam, K. et al. Impact of microplastics on soil (physical and chemical) properties, soil biological properties/soil biota, and response of plants to it: a review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-024-05656-y

Follow the Topic

-

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (IJEST) is an international scholarly refereed research journal which aims to promote the theory and practice of environmental science and technology, innovation, engineering and management.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in