The largest bird on Earth suffers in the hot and cold

Published in Ecology & Evolution

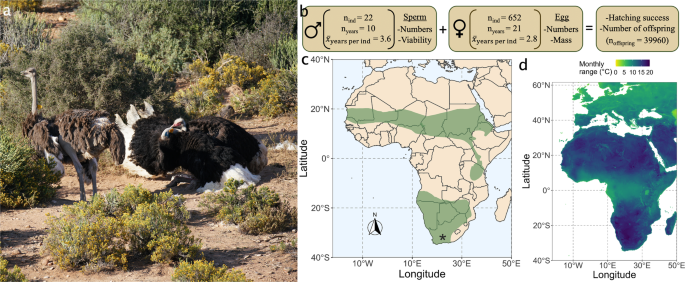

Oudtshoorn Research Farm in South Africa has been home to almost 1300 adult ostriches. Here these giant flightless birds are kept in pairs under the open sky, exposed to the heat and cold of the arid land while their reproduction is closely monitored. This dinosaur like bird has the amazing capability to reproduce in a wide range of environments, from the Kalahari Desert to the temperate Cape. But which male or female reproductive traits set the limits for its success across such variable habitats?

My only experience of ostriches before visiting the farm had been the data in an excel spreadsheet that I was attempting to crack open. Charlie Cornwallis, my post-doc host, had explained everything about the study site and data collection so I thought I was ready for my first real-world ostrich experience. I was wrong. When I entered the gates to the farm, complaining how hot it was, my attention quickly turned sideways. Charlie had “forgotten” to mention that the first ostriches to greet you are the solitary males trained for sperm collection, which immediately push their 2.5 m tall bodies up against the fence and begin a courtship dance, which for a newcomer, can only be described as extremely terrifying and crazily bizarre! These males are trained to ejaculate into an artificial female which, unfortunately for me, requires that they are imprinted on humans, causing this overly zealous behavior.

Witnessing the reproductive efforts of these birds in this hot place changed the way I viewed their challenges. When I came home, I dived into the excel spreadsheet again. First on my mind was time-lag effects; physiological consequences of a hot day can last for several days, so we suspected that the temperatures, not during, but before producing gametes is key to understanding the ostrich thermal limits.

This perspective was crucial, and the stats confirmed that the most influential temperatures were those two, three and four days back in time. Using this thermal window, it turned out that despite the ability of ostriches to reproduce in quite extreme environments, their reproductive success is very sensitive to temperature fluctuations. Their optimal temperature is around 20-25°C, and both cold and hot days compromised sperm and egg production. The resulting reduction in reproductive success was drastic, with up to a whopping 40% reduction with just 5°C change in temperature. So even though ostriches seem capable of reproducing anywhere, their sensitivity to both hot and cold temperatures is actually quite acute.

Another surprising finding was that some female ostriches were repeatably more resilient to high temperatures than others. This made me think about the variation in the habitats where ostriches reproduce. Are there different reproductive strategies, or maybe even genetic differences, allowing them to reproduce in such different environments? We thought maybe the females that lay the most eggs in the heat simply lay smaller eggs. But the data revealed the opposite: they lay larger eggs. This suggests that some females might be more specialized in reproducing at extreme temperatures. I can’t wait to dig into this, and with the help of a 9-generation pedigree we hope to soon shed more light on the mechanisms behind this apparent specialization, and the potential of the ostrich to move its reproductive limits even further into a future where warmer, more fluctuating habitats await us.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Funny and fascinating story! Do you know how much an ostrich eats per day? And in the wild are they mostly herbivores with some carnivory?