The local circadian clock of the prefrontal cortex regulates sleep and mediates the effects of sleep deprivation on mood

Published in Neuroscience, General & Internal Medicine, and Anatomy & Physiology

Clinical depression ranks among the most common psychiatric disorders and is a leading cause of disability worldwide. Current antidepressant medications have unpredictable and underwhelming response rates, leaving many patients facing prolonged and repeated treatment trials before achieving symptom relief. The development of faster-acting, more reliably effective antidepressants depends on a deeper understanding of the neurobiological foundations of mood regulation and therapeutic mechanisms.

Depression is associated with dysregulated circadian rhythms, physiological cycles of approximately 24h which influence a wide range of biological and behavioural processes, including sleep. In addition, sleep is also regulated by mechanisms related to its homeostasis - the drive to sleep after long periods of wake. While disrupted sleep is strongly linked to depression, acute sleep deprivation (SD) has fast-acting antidepressant effects; over 50% of patients show a marked reduction in depressive symptoms within hours, although the benefits usually disappear after the first night of recovery sleep. The neurobiological basis of these effects remains poorly understood, reflecting the complex relationship between sleep and depression.

It has been previously shown that the modulation of neural glutamatergic plasticity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC)—a brain region heavily implicated in depression —plays a key role in the antidepressant effects of SD. Interestingly, the neurons of the PFC also exhibit circadian rhythmicity, controlled by local molecular “clockwork” and influenced by signals from the “master clock” of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. In our study, we investigated the relationship between the local PFC clockwork and synaptic plasticity processes in the regulation of sleep and the therapeutic response to SD.

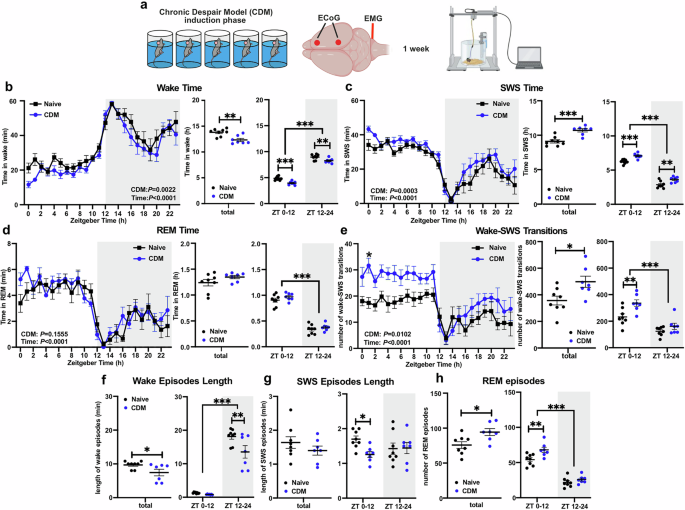

We utilised an established mouse model of stress-induced depressive-like state, that exhibits therapeutic responses and physiological changes, including dysregulation of the PFC clock. In this model, we observed disrupted sleep patterns and quality, alongside dysregulated day-night oscillations in the expression of Homer1a and AMPA synaptic receptors—two prominent markers of glutamatergic synaptic plasticity—in the PFC. These results indicate that disruption of sleep regulation and neuroplasticity mechanisms in the PFC are specific features of this depressive-like model, alongside previously established disturbances of the PFC clock. These changes add to the growing evidence of the importance of these mechanisms in the pathophysiology of depressive phenotypes. The mice also exhibited a blunted response to SD, characterized by impaired rebound of sleep and slow wave activity, and altered upregulation of the same plasticity markers. Together, these findings implicate mechanisms of sleep homeostasis as being specifically disrupted in depression; importantly, this aspect of sleep regulation has a direct relationship to synaptic plasticity, as described by the synaptic homeostasis hypothesis.

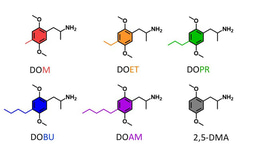

We then specifically explored the responses of the PFC molecular clock to acute SD, and compared this with the effects of low-dose ketamine, a well-established rapid antidepressant. The two treatments affected circadian clock gene expression in the PFC in different ways: while ketamine downregulated certain genes of the circadian clockwork, producing a sustained antidepressant effect, SD potentiated the expression of these same genes. Importantly, these genes have also been shown to be potentiated by repeated stress. This similarity between the action of stress and SD on the clock may explain the short-lived therapeutic action, and why depressive symptoms rebound after recovery sleep. These results suggest that while the therapeutic effects of both SD and ketamine are indeed mediated by modulation of the PFC clock, there is a mechanistic difference, potentially giving rise to the divergent outcomes.

Next, we examined the effect of direct disruption of the PFC molecular clock. Using an inducible knock-out model, we were able to specifically delete the essential clock gene BMAL1 in excitatory neurons of the PFC, effectively “breaking” the clock in these cells. While the circadian regulation of sleep is well-established, the role of the master clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus has always been considered primary; we demonstrate that selective genetic disruption of the local PFC circadian clockwork in excitatory neurons impairs the homeostatic regulation of sleep, reflected in fragmentation and abnormal slow wave activity. Furthermore, the response to SD is impaired in these animals, showing a lack of consistent recovery sleep, reflecting their broken homeostatic drive to sleep. The therapeutic effects of SD were also absent, an effect that appears to be mediated by the dysfunctional clock blocking the induction of the plasticity marker, Homer1a. In support of this finding, we also showed that pharmacological modulation of the circadian clock to suppress BMAL1 expression also blocked the rapid antidepressant effects of SD. These results show that the local PFC circadian clock has a direct influence on the homeostatic regulation of sleep. Disruption of this local clock is sufficient to affect sleep and mood-related behaviours, even when the central circadian clock is intact.

Take-home message

Our work highlights the critical role of the local PFC circadian clock in sleep regulation—including sleep homeostasis—and the behavioural response to SD. This indicates a potential link between mechanisms of circadian regulation and synaptic plasticity processes. These results add to our understanding of how the circadian biology of the PFC influences the complex relationship between mood and sleep. In the long term, these findings could help the identification of novel drug targets and facilitate the development of circadian antidepressant strategies, with the goal of increasing the effectiveness of current treatments.

Follow the Topic

-

Molecular Psychiatry

This journal publishes work aimed at elucidating biological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders and their treatment, with emphasis on studies at the interface of pre-clinical and clinical research.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in