The question is not whether SSRIs are universally good or bad, but how best to support maternal mental health

Published in Sustainability, Biomedical Research, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

In maternal mental health, few topics are as emotionally charged and scientifically complex as treating depression and anxiety during pregnancy. As rates of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders rise, expectant families face difficult treatment choices that are scientifically uncertain and personally consequential.

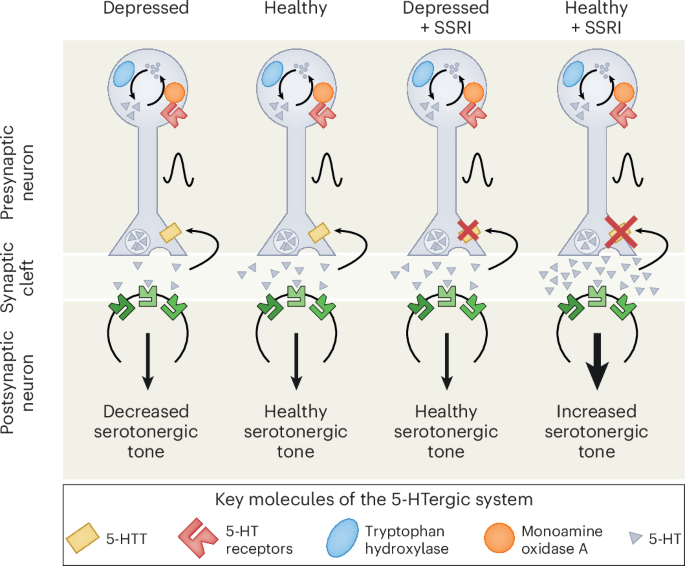

Our recent Perspective in Nature Mental Health highlights this tension. Despite decades of research on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in pregnancy, much public discourse and portions of scientific literature remain focused on potential risks to child development. However, our examination of the data suggests we might not be asking the right questions.

To delve deeper, I spoke with Dr. Tim F. Oberlander, a leading expert in perinatal psychopharmacology. His research has shaped the modern conversation about how prenatal exposures, including medications, interact with maternal health and the environment to influence developmental trajectories. In our conversation on Mommy Brain Revisited (#61), we discussed the motivations behind our Perspective and the conceptual shift we believe the field must undertake.

Dr. Oberlander emphasized that maternal mental health is the central issue. SSRIs are a crucial therapeutic approach that for many women but must be considered within the broader context of a mother’s emotional well-being before, during, and after pregnancy. In clinical care and research, we often lose sight of this. The discussion becomes an “SSRI story”—focusing on dangers and negative outcomes—instead of a story about the well-being of the mother and family.

The focus should always return to maternal wellness, which shapes pregnancy, birth outcomes, early caregiving, and child development.

The challenge is that depression during pregnancy is associated with a variety of adverse outcomes. This complicates understanding medication effects: are we observing the impact of SSRIs, depression, or the genetic, social, and environmental factors contributing to depression? Differentiating these factors is extremely difficult. Unlike studies of blood pressure medication or antibiotics, randomized controlled trials of antidepressants in pregnant populations cannot be ethically conducted. Thus, all research in this area relies on observational data, confronting the problem of confounding by indication—where the reasons for treatment may also influence the measured outcome.

To approximate causal inference, researchers use large administrative datasets, sibling-comparison designs, discontinuation-versus-continuation analyses, propensity score matching, and genetic information integration. These methods help simulate the “randomness” provided by randomized trials. Yet, most studies converge on a similar conclusion: initial associations between prenatal SSRI exposure and child developmental risks tend to diminish after accounting for maternal depression severity, family mental health history, socioeconomic factors, and other social determinants of health.

Such attenuation of the SSRI effects matters. It tells us that SSRIs often act as markers for underlying vulnerabilities rather than as primary drivers of child outcomes. A mother’s genetic predisposition to anxiety or depression, shared with her child, may contribute to her need for an SSRI and to behavioral traits observed later in her child. Without this accounting, cause can be easily misattributed. As Dr. Oberlander puts it, prenatal SSRI exposure may function like a “hitchhiker” on the back of inherited genetic risk or environmental stress.

Acknowledging this complexity does not leave clinicians without guidance. The evidence supports a clear message: maternal mood profoundly matters, and untreated depression and anxiety carry real risks. There is no risk-free option.

Clinicians and families must shift from asking, “Are SSRIs safe?” to asking, “Who is likely to benefit from SSRIs, and under what conditions?” Current data suggest that women with moderate to severe depression during pregnancy may benefit from pharmacotherapy, particularly when combined with non-pharmacologic interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, sleep support, exercise, and strong social relationships.

Another important insight from our conversation is that science often biases toward finding harm. Most studies of medication exposures in pregnancy are designed to detect adversity, not resilience. Thus, potential benefits of SSRI use—such as stabilized mood and improved maternal functioning—may go unexamined. Dr. Oberlander and others have begun publishing evidence suggesting that, for some families, prenatal SSRI exposure may support adaptive developmental outcomes in children, depending on the interplay between genetics and environment.

Researchers must design studies that ask not only “What are the risks?” but also “Who is protected, and why?”

Even as the science evolves, clinical reality remains personal. Shared decision-making—not formulas or one-size-fits-all rules—lies at the heart of effective perinatal mental health care. Decisions about initiating or continuing SSRI treatment must consider symptom severity, functional impairment, personal values, access to therapy, social support, and cultural beliefs about medication. Care must extend beyond pregnancy. Longitudinally monitoring mothers and children—tracking mood stability, developmental progress, and family well-being—provides a more accurate picture of outcomes than snapshots taken at birth or during infancy.

We also can’t ignore the cultural challenges surrounding antidepressant use in pregnancy. Many women face stigma or judgment when considering medication, even when clinically appropriate. This stigma reflects broader societal discomfort with mental health and a lack of public understanding about the real risks of untreated illness. As Dr. Oberlander notes, addressing perinatal mental health requires not just clinical care but also a public-health approach: improving access to services, integrating mental health into routine prenatal care, and reducing the shame associated with these disorders.

We also can’t ignore the cultural challenges surrounding antidepressant use in pregnancy. Many women face stigma or judgment when considering medication, even when clinically appropriate. This stigma reflects broader societal discomfort with mental health and a lack of public understanding about the real risks of untreated illness. As Dr. Oberlander notes, addressing perinatal mental health requires not just clinical care but also a public-health approach: improving access to services, integrating mental health into routine prenatal care, and reducing the shame associated with these disorders.

Ultimately, prenatal exposure to SSRIs in pregnancy is not only a story about developmental exposure to a class of medications. It is about health—the health of mothers, children, and families. It recognizes depression as a significant public-health concern, ensuring access to evidence-based treatments, supporting resilience, and understanding that long-term, relational care is essential.

The question is not whether SSRIs are universally good or bad, but how best to support maternal mental health to foster optimal developmental outcomes.

For clinicians seeking evidence-based guidance on treating perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, resources like the CANMAT guidelines offer comprehensive frameworks. Even the best guidelines must be applied with empathy, nuance, and an appreciation for the complex factors shaping each family’s experience. The science may be intricate, but the message is straightforward: maternal mental health matters, profoundly and unequivocally, and supporting it is one of the most important investments we can make in the well-being of mothers and of the next generation.

About the authors:

Dr Jodi Pawluski, PhD, PMHC, is a Neuroscientist, Therapist and Author of Mommy Brain . She is an affiliated Researcher at The University of Rennes, France.

Prof Tim Oberlander , MD, is a Developmental Pediatrician, Clinician-Scientist and Professor of Pediatrics in the School of Population Public Health, University of British Columbia and BC Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, Canada.

Our Perspective in Nature Mental Health: Pawluski, J., Oberlander, T.F. Potential risks and benefits of prenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications for maternal mental health and child development. Nat. Mental Health 3, 1304–1310 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00480-w

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Mental Health

This journal takes an expansive view of the relationship between mental health and human health. It brings together innovative investigation of the neurobiological and psychological factors that underpin psychiatric disorders to contemporary work examining the effects of public health crises.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in