The Retinal Pigment Score: changing the game in ophthalmology by decoupling ethnicity from biology

Published in Physics, Computational Sciences, and Genetics & Genomics

Over the past five years, the scientific community has increasingly recognised that ethnicity/race does not accurately reflect biological differences among humans. The global community has acknowledged that variable skin pigmentation has real-world consequences for medical devices (e.g., pulse oximeters, leading to increased risk of death) and standard facial recognition algorithms (resulting in poor performance in people with more pigmented skin tones). This has implications for art, photography, and inherent bias in technologies like self-driving cars that may not recognize certain individuals. Such algorithmic performance disparities stem from unrepresentative training datasets, which are challenging to measure and improve.

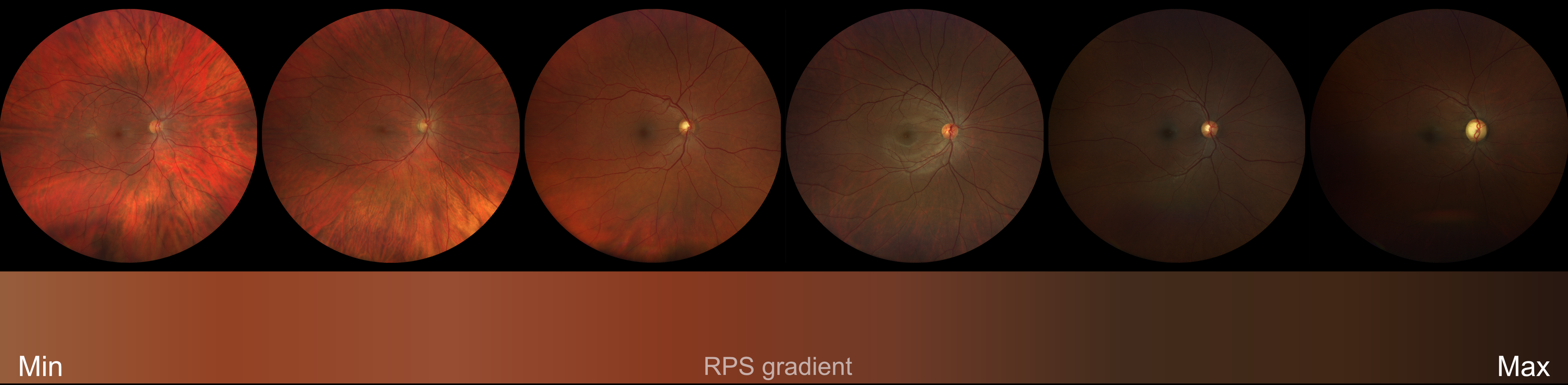

In ophthalmology, we observed that retinal images exhibit a wide range of pigmentation, even among people with similar self-reported ethnic/race backgrounds, skin tones, or hair colours (Figure 1). Yet, unlike our colleagues in dermatology, who use systems like the Fitzpatrick Skin Type or the Monk Skin Tone Scale as methods to objectively classify skin pigmentation, ophthalmology lacked tools to quantify this variability. Instead, we often use ethnicity/race as a proxy for biological differences. For instance, when testing an artificial intelligence (AI) model, we evaluate the model performance when tested on different ethnic/race groups. This approach is problematic. Although ethnicity/race may estimate the advantages or disadvantages an individual may experience in society due to their ethnic/race identity, ethnicity/race is, in part, a social construct and cannot capture the continuous spectrum of traits seen in real life. Additionally, this information is rarely, or incompletely, reported in datasets of retinal images for a variety of reasons related to the healthcare setting, legal framework and approach to open access data. Recognising this gap, we set out to create a standardised, objective measure: the Retinal Pigment Score (RPS) derived directly from the retinal image without recourse to a human labelling step (another potential source of human bias).

Figure 1. Retinal images from different people showing evident differences in background degree of pigmentation.

This lack of measurement tools is particularly pressing in AI research using retinal imaging. Underrepresented groups often remain excluded from curated datasets, limiting the ability of AI models to deliver equitable care. Addressing this inequity became a key aim of our project. The RPS offers a continuous measure of retinal pigmentation, enabling more accurate descriptions of retinal images and deeper insights into patient phenotypes.

Our task was challenging. Using advanced computer algorithms, we developed a method to extract background retinal pigmentation from retinal images. This algorithm uses deep learning models to identify and exclude poor-quality images, focuses on relevant regions, and then calculates an average pigmentation value, resulting in a single continuous metric: the RPS.

With the RPS in hand, associations of RPS with demographic variables and genetic studies showed extremely interesting results. We uncovered links between RPS and traits like hair, skin, and eye colour. Even more excitingly, we identified three new genetic regions that could unlock secrets about pigmentation in the retina itself. These findings not only validated the RPS biologically, but also highlighted its power to drive new discoveries.

Perhaps most strikingly, the RPS also challenged assumptions about ethnicity/race. We found significant overlap in pigmentation scores across different ethnic/race groups, reinforcing the limitations of using ethnicity/race as a predictor in clinical research, or of using RPS to predict ethnicity/race. The RPS provides an objective, continuous measure that could transform how retinal images are described and studied.

Behind this project was a multidisciplinary team from four countries, united by a shared commitment to equitable, patient-centred care. Our methods are transparent, and our code is freely available on GitHub, inviting others to use and build upon our work. The RPS is a significant first step forward to achieving equitable AI tools, not just for ophthalmology, but in all fields that use retinal imaging, such as primary care, cardiology and neurology. We are looking forward to collaborating with international researchers and clinicians to incorporate the RPS into prediction models and advance retinal research.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Your space to connect: The Macular degeneration Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Ophthalmology and Eye Diseases!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in