The Role of Historical Carbon Emissions in Climate Cooperation

Published in Earth & Environment

The sixth IPCC synthesis report, published in March 2023, warns that global warming will likely exceed 1.5°C during the 21st century even if the emissions stay below the nationally determined contributions announced in 2021. These findings highlight the urgency of taking more drastic action in the upcoming COP28 climate summit. Successful global cooperation to resolve the climate crisis has been difficult partly because of enormous differences in historical carbon emissions: Developed countries in Europe and North America have emitted about twice the amount of the Asian countries, which developed more recently (Figure 1). Our recent paper in Nature Communications uses laboratory experiments to study how the historical imbalances and attribution of historical emissions affect international cooperation on climate change mitigation.

.png)

The international community has debated for a long time whether the burden of climate change mitigation should be divided based on historical carbon emissions. Brazil’s proposal to explicitly include the principle of historical responsibility in the Kyoto Protocol was ultimately rejected, but similar proposals have resurfaced time and time again. In 2019, developing countries proposed to establish a Loss and Damage Fund, through which the largest historical emitters would compensate poorer countries that are most vulnerable to climate change. The Loss and Damage Fund was finally approved at the COP27 conference. The details of the size of the fund and the contributing countries are yet to be decided at the upcoming COP28 climate summit, thus historical emissions will likely take the center stage in the upcoming climate negotiations.

The crux of the disagreement lies in whether the current generation should be responsible for the carbon emissions of their predecessors. On one hand, many current taxpayers in developed countries were not even born when the bulk of carbon emissions were generated, thus they carry no personal responsibility for the historical emissions. On the other hand, some believe that the current generation should pay because their current wellbeing is predicated on their country’s industrial past.

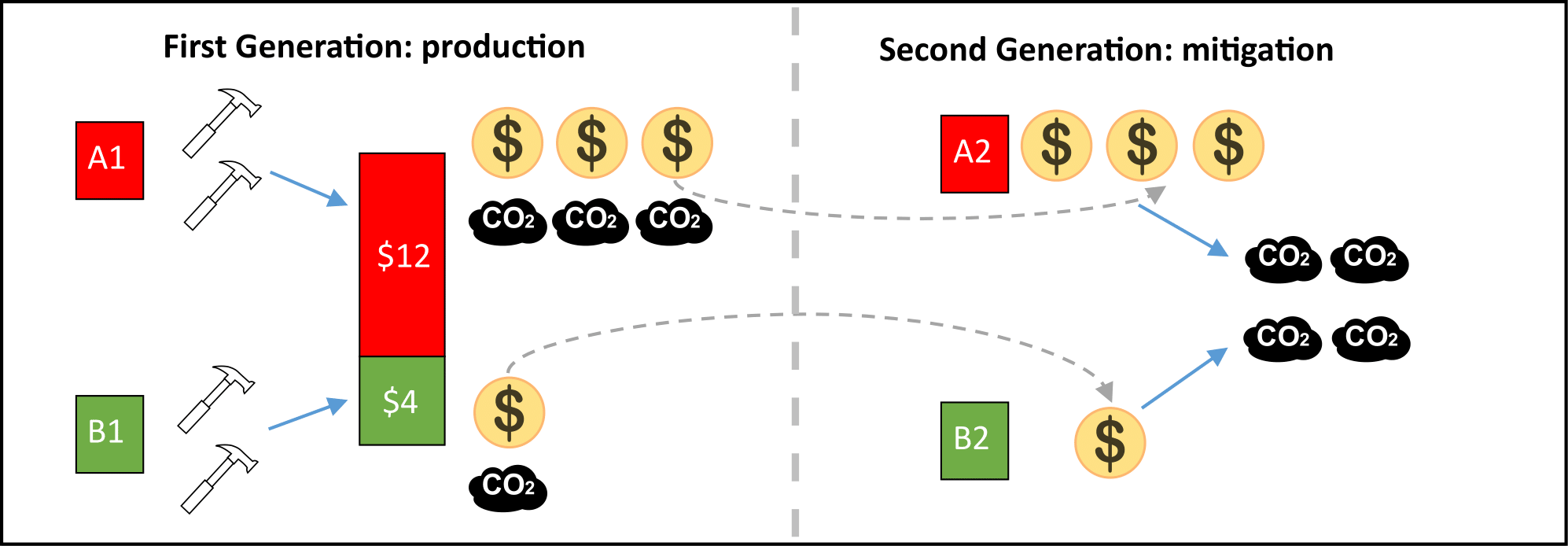

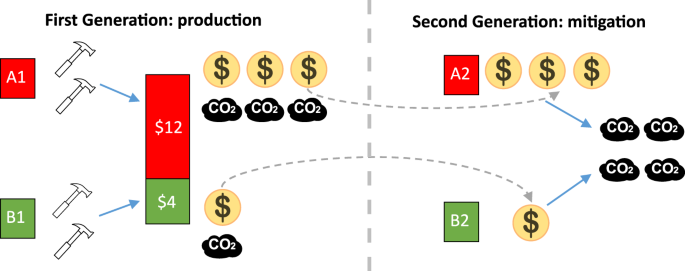

Since it would be difficult to study the role of historical responsibility in real-life climate change negotiations, we searched for answers using laboratory experiments (Del Ponte et al. 2020). We designed an intergenerational climate game in which two players were the first-generation leaders of countries A and B, while two others were the leaders in the second generation. The first generation decided how much to produce, which created wealth for themselves as well as exponentially larger carbon emissions. Their second-generation successors inherited the wealth of the respective predecessor but had to agree on how to divide the costs of climate change mitigation, determined by the total emissions of their predecessors (Figure 2). If they failed to reach an agreement, both players would face a high risk of a climate disaster that would destroy all earnings. The second-generation leaders therefore could not influence their ancestor’s emissions, but they benefited from higher emissions, just as the current citizens of developed nations.

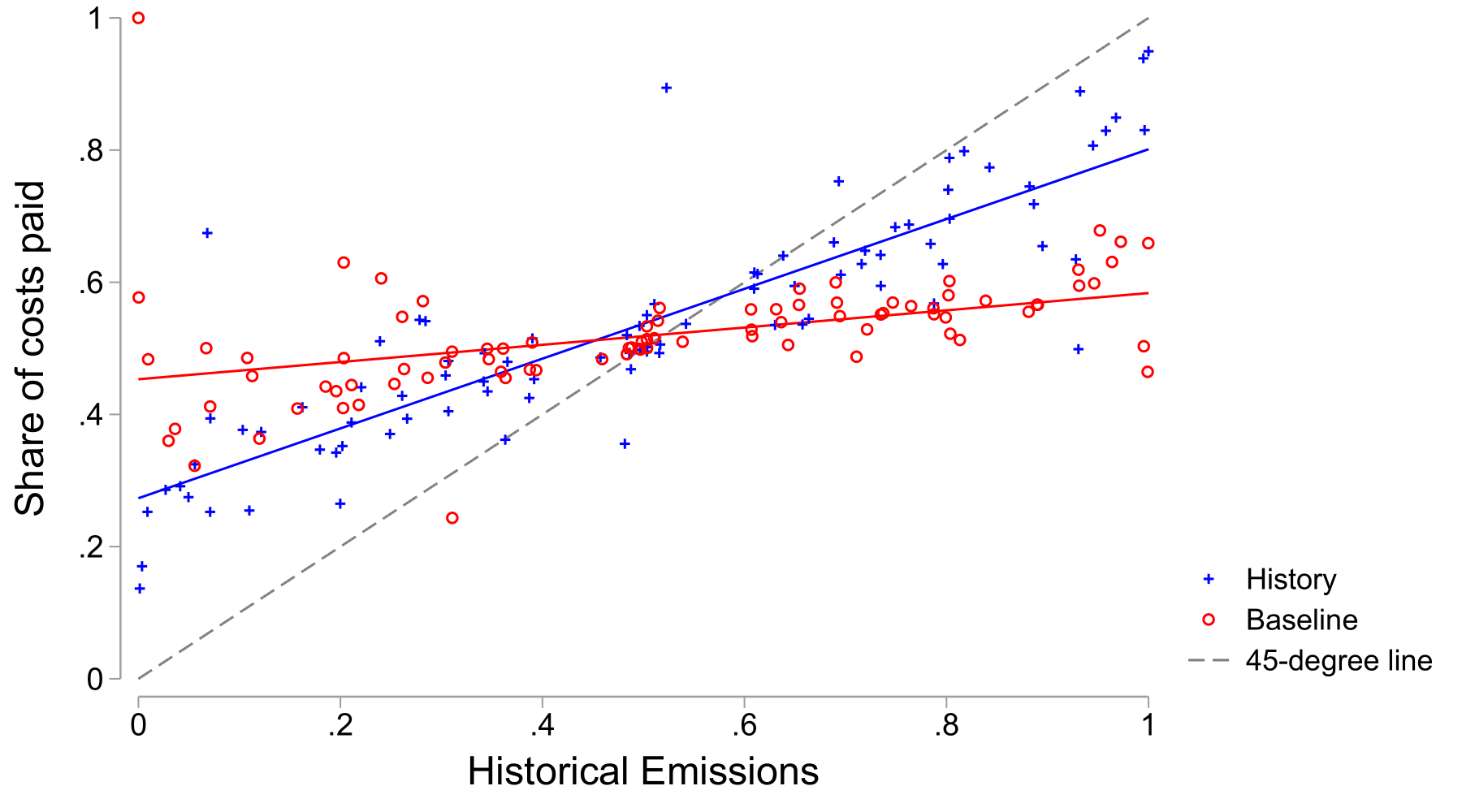

The key factor in our experiment was whether the second generation knew that their wealth was created by the predecessor’s emissions, and thus linked with the current climate change crisis. We find that participants who received this information were more likely to divide the climate mitigation costs proportionally to historical emissions (blue markers in Figure 3), while the uninformed participants in the baseline treatment were more likely to split the costs evenly (red markers in Figure 3). We also studied how information about history affected the chances of reaching an agreement. More accurate attribution of historical emissions, such as shown in Figure 1, introduces an alternative fairness norm, which might lead to more disagreements if each party favors the norm that advances their own interests (Underdal & Wei 2015). In our experiment, such fears are unfounded, as historical information did not lead to fewer agreements. Frequent agreements were facilitated by the participants with high historical emissions, who offered to pay more. Offering to pay proportionally to historical emissions was in fact beneficial to such participants, as lower offers were often rejected and created large losses from a climate change disaster. Taken together, these results suggest that when historical emissions can be accurately attributed, as is the case today, the success of climate agreements rests on the developed countries taking responsibility for their historical emissions.

Figure 3. Share of climate change mitigation costs paid by second-generation participants and historical carbon emissions created by their predecessors. When participants had precise information about their predecessors’ contribution to historical emissions (History treatment: blue markers), the share of the costs that they paid was more proportional to the historical emissions generated by their predecessors compared to when the precise attribution of historical emissions was unavailable (Baseline treatment: red markers). The red and blue lines indicate the best linear fit to the data. The 45-degree line shows how costs would be divided if they perfectly corresponded to historical emissions.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in