The social cost of carbon has increased over time

Published in Social Sciences

The social cost of carbon is the damage done to human welfare by emitting one additional ton of carbon dioxide. If the world were ruled by a benevolent dictator, Plato’s philosopher-queen or Confucius’ good Duchess Zhou, this is the tax that she would impose on greenhouse gas emissions. The social cost of carbon is an arcane concept in economics – the monetized marginal net present welfare along the optimal emissions trajectory – but one that guides decisions on climate policy by governments around the world. It is a contentious subject. In the USA, the Obama Administration introduced an official social cost of carbon, and later revise it upwards. The Trump Administration reduced it to zero at first but was told by the courts to increase it again, albeit only a little bit. The Biden Administration reversed the social cost of carbon to the second Obama one and is likely to raise it further in the near future.

Against this political backdrop, I set out to explore whether the academic estimates of the social cost of carbon had changed over time. Between 1982 and 2022, 207 papers have been published with a total of 5,905 estimates of the social cost of carbon. There are so many estimates because the social cost of carbon is important yet hard to pin down for two main reasons. The social cost of carbon is the incremental damage in the future. The future is inherently uncertain. Our understanding of emissions, climate, and impacts today is incomplete, let alone hundred years from now. The second reason is that the impacts of climate change differ greatly over time, across space, and between scenarios. Reasonable people reasonably disagree on how to aggregate over these dimensions. The discount rate, how to add impacts at different points in time, has attracted most attention but is certainly not the only value-laden decision made when estimating the social cost of carbon.

The uncertainty about the social cost of carbon span twelve (!) orders of magnitude, from -$771 per metric tonne of carbon to $107,260,751/tC. There are only a few estimates, 1.6%, that are negative. More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is a short-term boon for agriculture in poor, arid countries. The vast majority of estimates find that putting more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is bad. A small minority finds that it is very bad: If the carbon tax is set equal to the social cost of carbon, the tax paid would exceed total income. These estimates, some 5% of the total, were discarded because this is not possible. Another 15% of estimates is so large that, if levied as a carbon tax, all other taxes could be abolished but total tax revenue would still go up.

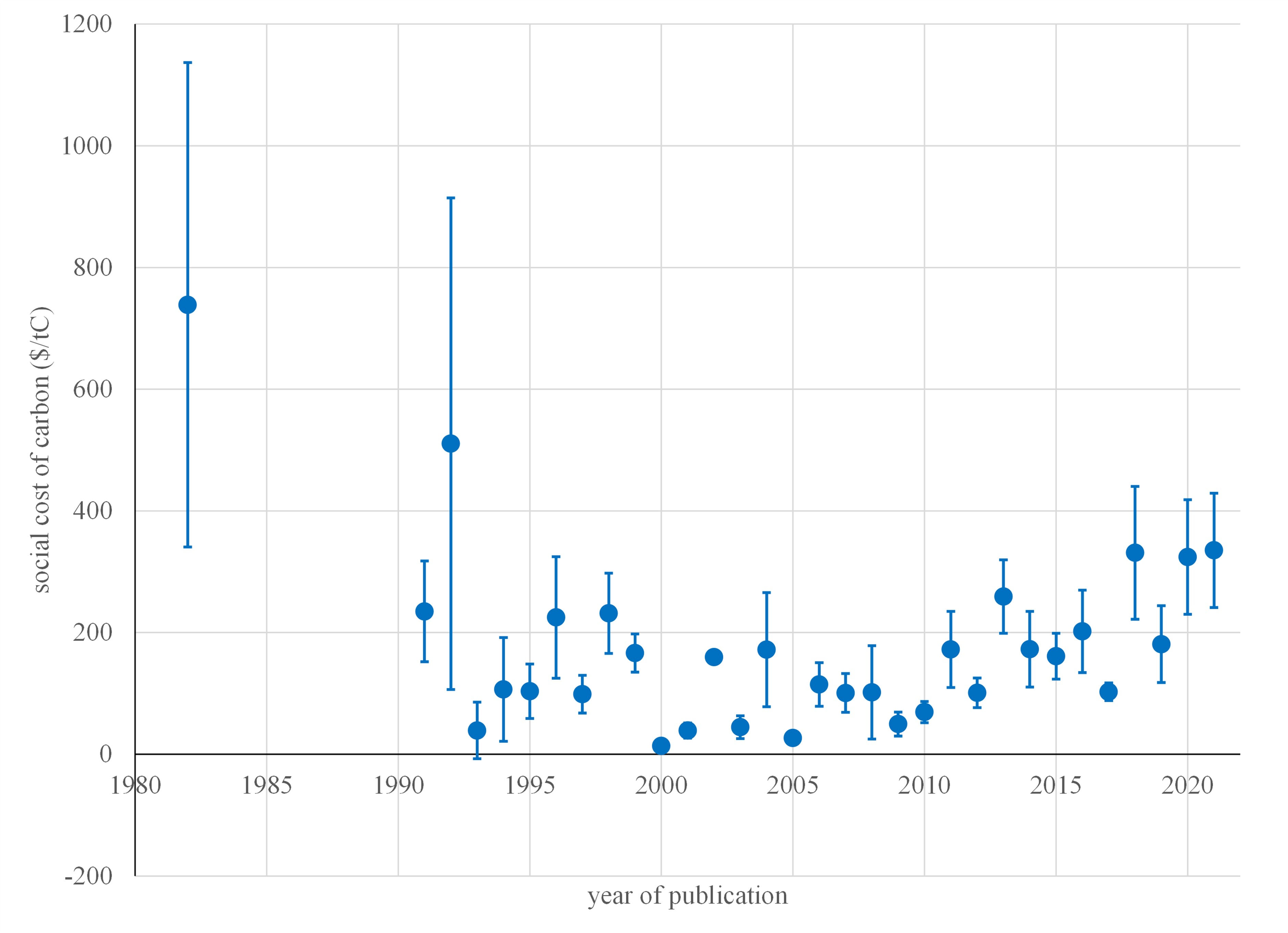

Such wide and asymmetric uncertainty stretches standard statistical methods perhaps beyond their breaking point. The range of estimates – normalized to 2010 US dollars and emissions in 2010 – per publication year shown in Figure 1 suggests an upward trend since 2000. However, researchers have tended towards using lower discount rates in recent years, inflating the estimates of the social cost of carbon. Controlling for this, the upward trend is statistically significant only if high-quality estimates are given extra weight and only in the lower and middle parts of the distribution.

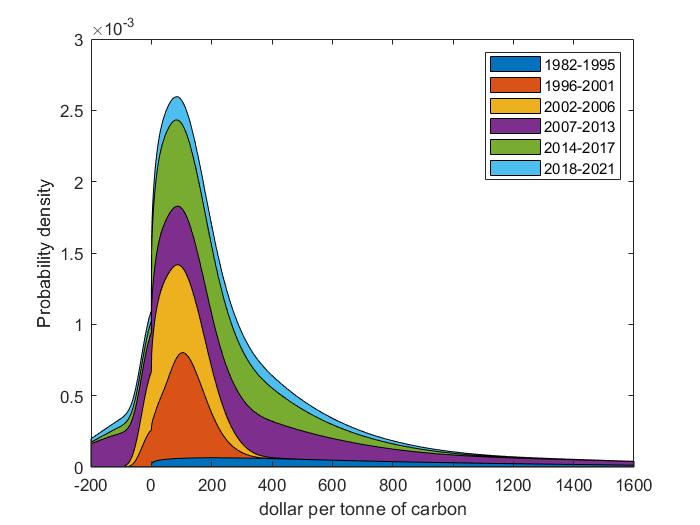

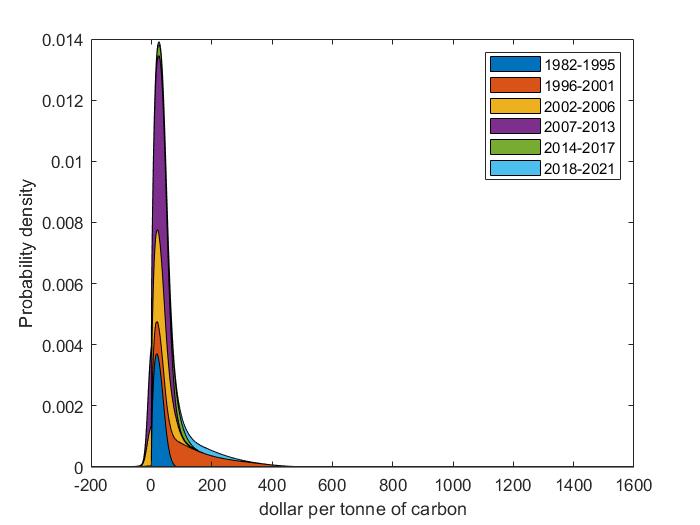

However, a new, bespoke statistical test does support the visual impression that estimates of the social cost of carbon have increased over time. The test uses kernel densities. A kernel density is a flexible probability density that does not force the data into any particular shape. In this case, the uncertainty about the social cost of carbon is large and asymmetric, with a thick right tail and a thin left tail. Furthermore, the weighted sum of kernel densities is a kernel density. This allows for a decomposition of any kernel density. Figure 2 decomposes the overall density by publication period for two commonly used utility discount rates. The finite sample version of Pearson’s test for the equality of proportions can then be used to test the null hypothesis that the component densities equal the overall density. This hypothesis is firmly rejected – also when controlling for the discount rate used. Estimates of the social cost of carbon have really increased – by more than a factor four in the last decade.

The Biden Administration is therefore correct to revise the official social cost of carbon – and revise it upwards as everyone expects it will. Other governments should do likewise. More importantly, however, the majority of greenhouse gas emissions – some 80% – are not priced at all. Now would be a good time to subject all greenhouse gas emissions to either cap-and-trade or a carbon tax.

Figure 1. Estimates (average plus and minus the standard deviation) of the social cost of carbon by year of publication.

Figure 2. Kernel density of the social cost of carbon and its decomposition by publication period for a pure rate of time preference of 1% (left panel) and 3% (right panel) per year.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Climate Change

A monthly journal dedicated to publishing the most significant and cutting-edge research on the nature, underlying causes or impacts of global climate change and its implications for the economy, policy and the world at large.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in