The Spark: Flexible Electronics Meet Sustainable Metals

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology, Chemistry, and Materials

The world of electronics has seen a remarkable transformation in the past few decades. From chunky mobile phones and boxy TVs to sleek, flexible designs to now futuristic gadgets that can be woven into our clothes or even our skin! This leap toward wearable and low-cost devices isn't just about design, it demands new manufacturing methods that are sustainable, energy-efficient, and compatible with delicate surfaces like plastic and paper onto which conductive circuits can be printed.

While silver and copper inks have dominated this space, they're costly and/or have limitations. Aluminium offers an attractive alternative: it's abundant, cheap, and nearly as conductive. But using aluminium isn't straightforward. Traditional deposition techniques rely on high-temperature processing or pyrophoric (i.e., spontaneously igniting) precursors like aluminium hydrides that are dangerous to handle, especially in air. That combustible nature has kept aluminium on the sidelines in flexible printed electronics.

The Challenge: Taming Aluminium Through Chemistry

Our team wanted to solve this: could we design a molecule that’s both stable in air and convertible to metallic aluminium at low temperatures (<200 °C)? The key idea was to design a precursor that could balance these two crucial properties. The best way forward appeared to be employing building blocks that stabilize the aluminium atom, slowing unwanted reactivity, yet still yielding clean conversion to Al(0) under mild heat.

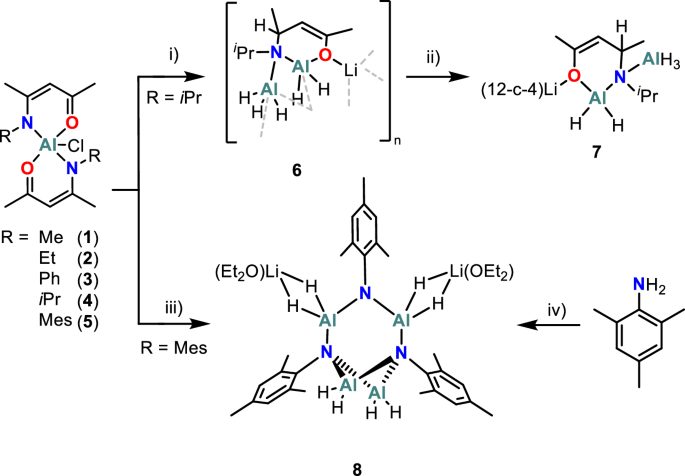

Our building blocks, known as ligands, employed two binding sites rather than one. Specifically we focused on β-ketoiminate ligands, known already in the broader field of vapour deposition. By varying slightly the blocks we were able to synthesize five aluminium complexes [Al(R-β-ketoiminate)2Cl] complexes, where R = simple short chain hydrocarbons. Next we attempted to swap the chloride for hydride groups (Al–H) via various pathways. Getting to Al–H bonds was crucial. They hypothesis was that these Al–H bonds would aid reduction of the Al(III) to metallic aluminium while also helping preventing its oxidation to the unwanted oxide.

After many trials, reactions with the reducing agent Lithal (LiAlH4) yielded some interesting results and we isolated two promising hydride species:

· Compound 6: Li[AlH₂(iPr-Hacnac)AlH₃]ₙ (a polymeric amidoalane)

· Cluster 8: [AlH₂AlH₂(N-Mes)₃(AlH₂·Li(Et₂O)₂)₂] (an imidoalane featuring bulky mesityl ligands)

8 turned out to be a game-changer. While others decomposed poorly, 8 cleanly converted to aluminium under surprisingly mild conditions.

The Eureka Moment: Non-Pyrophoric Aluminium Precursor

Heating 8 under vacuum at 100 °C for one hour or simply leaving it under nitrogen at room temperature yielded metallic aluminium. XRD, TEM, and XPS confirmed the transformation

A thin metallic film (~1 µm) on glass, with low sheet resistivity was obtained on glass from the ink synthesised by dissolving 8 in toluene, showing viability as a conductive ink . Most strikingly, unlike classical aluminium hydrides, this precursor does not ignite in air (it slowly oxidises without fire) making it much safer for industrial use.

The bulky mesityl groups provide crucial air-stability, while the Al–H bonds let it decompose cleanly. Resultantly, no external reductants or high sintering temperatures were needed. needed.

The Long Road: Trials, Tribulations, and Teamwork

This project was far from linear. Swapping chlorides for hydrides proved exceptionally difficult. We spent nearly three years iterating on ligand design and hydride chemistry:

· Initial attempts with common hydride sources failed or produced intractable mixtures.

· Only by tuning a complex ligand scaffold: β-ketoiminates plus mesityl groups—did we finally isolate cluster 8 in usable yield (~6–34%)

· Each hydride transfer had to be performed at –78 °C under inert atmosphere, followed by careful purification.

The long grind involved late nights, troubleshooting, pouring over data sources and getting help from the exceptional technical team at UCL. Several times we almost abandoned this avenue, but structural insights kept us going.

Impact: A Safer, Greener Aluminium Ink

This work unlocks a new path for aluminium inks that are air-stable yet convert to Al metal at ~100-150 °C and non-pyrophoric, meaning safer to handle in industrial environments.

It’s a step toward sustainable electronics. Low-cost, low-waste, and easily printable. And because aluminium is earth-abundant, this chemistry could significantly reduce reliance on costly silver or copper.

What’s Next: Scaling, Printing, and Integration

We’re already working on Ink formulation: dissolving cluster 8 in inks suited to inkjet or aerosol jet printing. Following this substrate testing is next, applying these inks on flexible plastics and paper, followed by low-temp curing. Performance validationis crucial, for example measuring conductivity, adhesion, mechanical flexibility, and conductivity under bending tests.

Lessons Learned

Firstly that ligand engineering is powerful: Bulky β-ketoiminates gave air-stability while preserving Al–H reactivity. Also persistence matters: Decades-old stubborn chemistry can yield breakthroughs with enough trial and error. We employed multidisciplinary teamwork to great effect; Chemists, materials scientists, and device experts collaborated across synthesis, characterization, and application. Finally and crucially we must put safety first: Designing around non-pyrophoric precursors made this route viable for real-world use.

Final Thoughts

We’ve shown a new way to harness aluminium, the third most abundant element, for next-gen electronics, with vision and safety in mind.

If you’re curious about synthesis details, characterization, or ink formulation, feel free to reach out. And stay tuned: aluminium printing on flexible substrates is closer than you think.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in