The ‘World’s Dumbest Bird’ can innovate to find food

Published in Ecology & Evolution, Zoology & Veterinary Science, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Explore the Research

Palaeognath birds innovate to solve a novel foraging problem - Scientific Reports

Scientific Reports - Palaeognath birds innovate to solve a novel foraging problem

The illusion of animal intelligence

Humans are obsessed with cognitive skills that make us ‘superior’ to other animals, and we construct rankings of ‘intelligence’ where humans conveniently always take the gold position (in other words, a fixed, one-horse race!). And as soon as you dip a toe into the animal cognition literature, you realise that only a few charismatic, ‘super smart’ taxa, namely the crows, great apes and dolphins, have competed against us in these Animal Olympics.[1] There are legitimate reasons for species biases in research (e.g., our evolutionary similarity to great apes, and crows/dolphins as examples of convergent evolution) but studying a handful of species also creates a false impression of a zero-sum game. Just because the species we repeatedly choose to study are capable of complex cognition (tool use, imitation, counting, etc.) this does not automatically make other species simplistic. We need to be transparent and challenge biases in comparative cognition research: does a species at the bottom of our intelligence ranking genuinely lack cognitive skills, was the test unfair to them (biased towards ‘human-ness’), or has the species not been tested at all?

Are big birds really ‘dumb’?

In 2015, avian biologist Professor Louis Lefebvre from McGill University stated that emus are the ‘dumbest bird in the world’.[2] Two pieces of current evidence support this view. First, ‘big birds’ (belonging to the ancestral Palaeognathae grouping including emus and ostriches, mostly giant and flightless) have the smallest brain sizes (relative to body size) of all the living birds. Second, a large-scale analysis of bird innovation[3] showed no evidence of technical innovation (the ability to invent a solution to a novel problem) in palaeognaths. However, one important type of evidence is absent for the palaeognaths. Unlike many birds, palaeognaths have not been tested for their physical cognition skills using controlled experiments. A lack of reported innovation could therefore reflect a lack of human interest in these species, inherent difficulties working with them, or assumptions based on their evolutionary proximity to extinct non-avian dinosaurs.

A personal journey

In 2023, I had the opportunity to study birds for the first time in my career (I am guilty of the aforementioned speciesism, spending two decades studying primates and dolphins). My interest in ‘big birds’ arose because palaeognaths and crocodilians are the closest living relatives of dinosaurs but almost nothing is known about their cognition (except for novel recent work on their social cognition).[4] Contrast this to a century of cognitive/behavioural work on the chimpanzee, the closest living relative of humans. Put another way, I suppose I had begun to question my own biases and how they fit within the wider field of animal cognition.

The steps to assessing palaeognath ‘intelligence’

A local zoo with three species of palaeognath (emus, rheas and ostriches) agreed to partner on my new research endeavour with students from the University of Bristol's School of Psychological Science. From the outset, palaeognaths were difficult to work with. We had no idea how palaeognaths would respond to cognitive tasks because the literature is focused on how to rear these birds for their meat (emus and ostriches are farmed in certain countries). Our species were large in stature (ostriches around 7 feet tall) with powerful beaks. We cautiously designed a task that could be attached to a fence at the bird's eye level to prevent kicking, stamping and throwing (techniques they use to hunt small prey!). Even though our birds spent long periods grazing on grass, they were motivated to grasp small and succulent lettuce leaves.

Our experimental design was unconventional for two reasons. First, unlike smaller birds and birds you might study in a lab, our birds could not be moved on command and were not trained. Therefore, we had to leave the task in the enclosure for long periods (30 mins) and re-fill it as needed. Second, we created an unusual design where birds had to align a hole with a piece of food. This might sound like an easy action, but it requires bringing two things together, rather than taking one thing from another.[5]

We observed one expected and one unexpected innovation

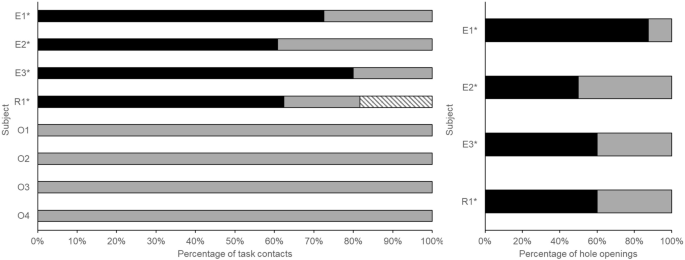

We designed a task with one solution in mind: align a hole with a piece of food and it’s yours. Emus and rheas were capable of innovating this behaviour (ostriches never did – we believe our female study group were particularly wary of novel objects). Even though repeated pecking is not a complex behaviour, their direction of pecking was not random (they moved the hole in the most efficient direction towards food not away from it in 90% of cases).

We did not expect to observe a second innovation. The male rhea (in a multi-sex pair) also twisted the bolt at the centre of the wheel to dismantle it. This happened twice and admittedly caused a commotion as we quickly retrieved the task from the enclosure. We did not design or expect the task to fall apart, and the video (see paper supplementary material) shows how the bird applied force to the bolt rather than a task fault. Interestingly, the bird did not continue with this strategy once it created the other innovation (moving the hole).

What are the implications of the study?

This research revealed, for the first time, palaeognath’s capacity for technical innovation. Based on previous strong correlations between bird brain size and cognitive skill, I knew that we would not find crow-level innovation skills in palaeognaths. However, their efficient task use (moving the hole in the efficient direction most of the time) surprised me. After reading about farmed birds and hearing anecdotes, I expected the birds to be chaotic and random in their movements.

I hope our research piques more scholarly interest in palaeognath birds. A logical next step is to make a fair comparison with other birds, testing them all on the same task. But palaeognaths are a lot larger and stronger than other birds - a delicate little puzzle box is inappropriate for them. I also hope that more ‘underdog’ species in the animal kingdom are studied, in creative ways, outside the laboratory. Finally, I encourage all animal researchers to study a new species at least once in their careers. As a die-hard primatologist/cetologist, this experience has reminded me to challenge speciesism and avoid subscribing to fables about animal intelligence.

References

- Farrar, B. G., Altschul, D. M., Fischer, J., Van Der Mescht, J., Placì, S., Troisi, C. A., ... & Ostojić, L. (2020). Trialling meta-research in comparative cognition: Claims and statistical inference in animal physical cognition. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 7(3), 419.

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/describing-someone-birdbrained-misguided-unless-youre-talking-about-emus-180958981/

- Sol, D., Olkowicz, S., Sayol, F., Kocourek, M., Zhang, Y., Marhounová, L., ... & Němec, P. (2022). Neuron numbers link innovativeness with both absolute and relative brain size in birds. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 6(9), 1381-1389.

- Zeiträg, C., Reber, S. A., & Osvath, M. (2023). Gaze following in Archosauria—Alligators and palaeognath birds suggest dinosaur origin of visual perspective taking. Science Advances, 9(20), eadf0405.

- Webster, S. J., & Lefebvre, L. (2001). Problem-solving and neophobia in a columbiform–passeriform assemblage in Barbados. Animal Behaviour, 62(1), 23-32.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Women’s Health

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in