Time is Precious

Published in Protocols & Methods, Cell & Molecular Biology, and Genetics & Genomics

In the rapid progression of science, time seems to fly by. Imagine it was only 12 years ago the term long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) was solidified – despite their discovery numerous years prior. As the decades have passed it has been inspiring to witness lncRNA going from transcriptional byproducts to potential therapeutics and a burgeoning biotech industry. However, we may have missed something along the way and this recent study shows what.

Of course, science is always self-correcting, and there have been numerous course corrections over the years, guided by healthy criticism. Embracing these criticisms has trued the course to elucidate the regulatory potential of lncRNA. For example, our laboratory has been studying the lncRNA termed FIRRE for over 15 years and yet we have only recently realized we missed something critical: TIME.

The clue came when studying the role of the lncRNA Firre in vivo. The goal was to use a transgene copy of Firre in a knockout mouse background to rescue defects in blood development due to the removal of the Firre locus. Not only did the Firre transgene rescue these physiological defects, but it also restored the underlying gene expression signatures – thus demonstrating that the lncRNA Firre is trans acting and functions using an RNA-based mechanism.

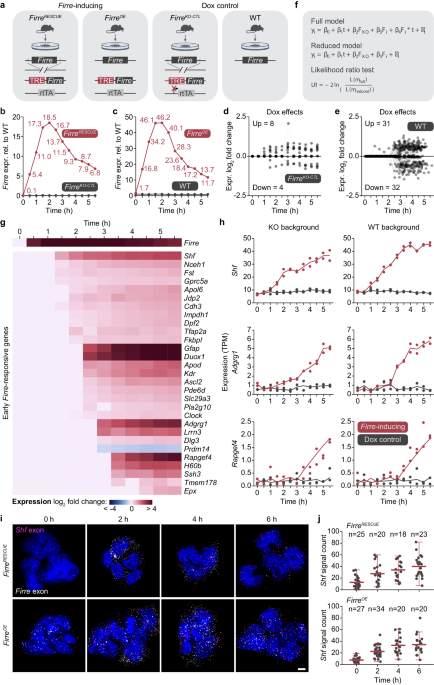

The more we thought about mechanism the more we thought about time – what was the order of events? If we compare wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) Firre backgrounds, we observe hundreds of genes with changed expression. Thus, determining the order of events is impossible. We needed a reliable system to track Firre across time to observe the earliest regulatory events that lead to a cascade of transcriptional changes.

There was a lot of debate, in the lab, on the best way to approach this question and in the end, there is no perfect system – the best you can do is have built-in controls to identify artifacts. To this end we genetically engineered two distinct, inducible Firre-transgene mouse stem cell lines. This would allow us to determine the temporal ordering of gene regulatory events.

To be honest, when we first acquired data from 0,12,24, 48 and 96 hours after inducing Firre we had no idea how best to interpret the data. We were pleased to observe the transgene restoring the KO signature back towards WT – again confirming an RNA-based trans-acting regulatory role for Firre.

Then the next clue came from the finding that many genes change in expression after 12 hours, raising the question: what happened even earlier? We proceeded to evaluate a more refined time course of every 30 minutes after Firre induction (rather than the original every 12 hours). Indeed, we found a small set of genes that were mostly upregulated around 2 hours after Firre was induced. With one key exception: Prdm14 (we’ll come back to this) was down regulated.

This became a fun question across the lab: what happened earlier? So, we next looked even earlier by performing an ATAC-seq time course from the moment of Firre induction to 2 hours (in 30 min intervals). Strikingly, we found that after 30 minutes chromatin accessibility was moving from closed to open near the same 10 genes that were all activated after 2 hours. The order of events was now becoming clear. After 30 minutes of induction of Firre, chromatin accessibility changed at just a handful of sites, and then the corresponding genes became activated. Thus, the two layers of evidence (ATACseq and RNAseq) had pointed us to 10 very robust and early regulatory events by Firre.

So of course, we asked: what happens earlier? To answer this, we performed nascent RNAseq (PROseq) for 15 and 30 minutes after Firre induction. Remarkably, the de novo chromatin accessibility sites also demonstrated de novo nascent transcription, indicating that RNA Polymerase II was recruited or activated at these very specific sites. Thus, by understanding the temporal dynamics of when and where a lncRNA functions, we limited the possible mechanistic models dramatically.

We had now observed that in minutes chromatin accessibility is opened, in minutes nascent transcription is induced, and after two hours the mature mRNA is activated. Thus, the Firre must directly act within minutes of inducing the trans-gene. Since the timescale of the first event is minutes, it suggests that Firre must be interacting and influencing existing molecules in the cell (DNA, protein or RNA). Importantly, these events are occurring before a new mRNA could be produced, translated and the resulting protein re-imported to the nucleus. Thus, the most likely explanation was that Firre binds to its sites of action and induces the changes with “poised” or existing molecules in the nucleus.

We tested this model by single molecule RNA-FISH (smRNA-FISH) using probes to target the Firre lncRNA and its DNA regulatory sites. To our surprise, we did not observe Firre localizing to these DNA locations. This led us to think that Firre must be interacting with an existing RNA or protein in the nucleoplasm, that in turn influences the epigenetics of DNA.

This now brings us back to Prdm14, a transcription factor that was downregulated around 2 hours after induction of Firre. Thanks to a reviewer’s suggestion, we performed “gene ontology” (GO) analysis for the gene expression signature Firre restored after 12 hours. Shockingly, the most significant enrichment was associated with a Prdm14 Knockout! Thus, a plausible mechanism would be that Firre initially down-regulated Prdm14 – which in turn resulted in the larger transcriptional cascade after 12 hours. In the end, time allowed us to greatly reduce the mechanistic possibilities, and we are making progress towards a conclusive answer.

Moving forward we now know the exact location for the most immediate, primary regulatory events of Firre. Thus, we propose that the best way to determine mechanism is to use these sites as “probes” to determine all the molecular components contributing to this mechanism. A common practice is to find the protein bound to a lncRNA and derive mechanism from there. However, we have tried this for over 15 years and have always been misled by binding events that are detectable but not functional.

Based on my 25 years of experience working on lncRNA, I now suggest an unconventional path towards temporally grounded, and thus more realistic, models of lncRNA mechanism.

First, the primary or most immediate sites of regulation must be determined. These sites can then be made into reporter genes (e.g., GFP). Then a genome wide loss-of function screen (e.g., CRISPR-I or CAS13) of all genes will reveal which genes are required to activate the reporter – thus those genes are involved in the mechanism. If a gene is lost and the reporter can no longer be activated by Firre, that gene must be involved somehow. Then after we know all the players in the pathway, we will look for RNA-protein interactions driving the mechanism.

In short, I hope I’ve conveyed the simple message of how important understanding the temporal dynamics of lncRNA-based regulation is towards resolving mechanism – as many mechanisms are simply not consistent with short time scales. And none of this could have come to pass if not for the incredible inspiration and resilience of the Rinn lab members past and present.

Now it is time to translate the potential of lncRNA-mediated epigenetic regulation into therapeutic strategies!

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in