Unfortunately you are not authorized to view that page.

Turning Noise into Knowledge: Tracing Fault Damage After the 2014 Nagano Earthquake

Published in Earth & Environment

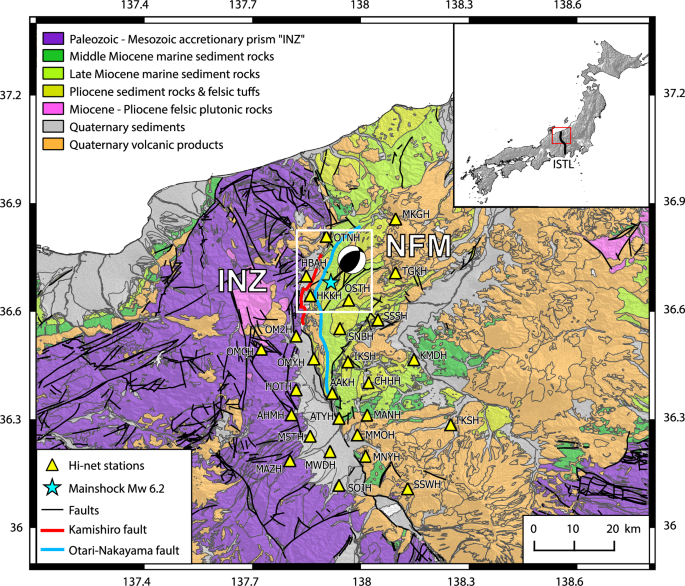

In November 2014, the ground beneath the region of Nagano, in Japan, shook violently. The magnitude 6.2 earthquake along the Kamishiro fault induced visible fractures across the surface that split roads and displaced homes. Yet, for us, the most fascinating part of this story was hidden: the distribution of the weakening and damage within the Earth’s crust.

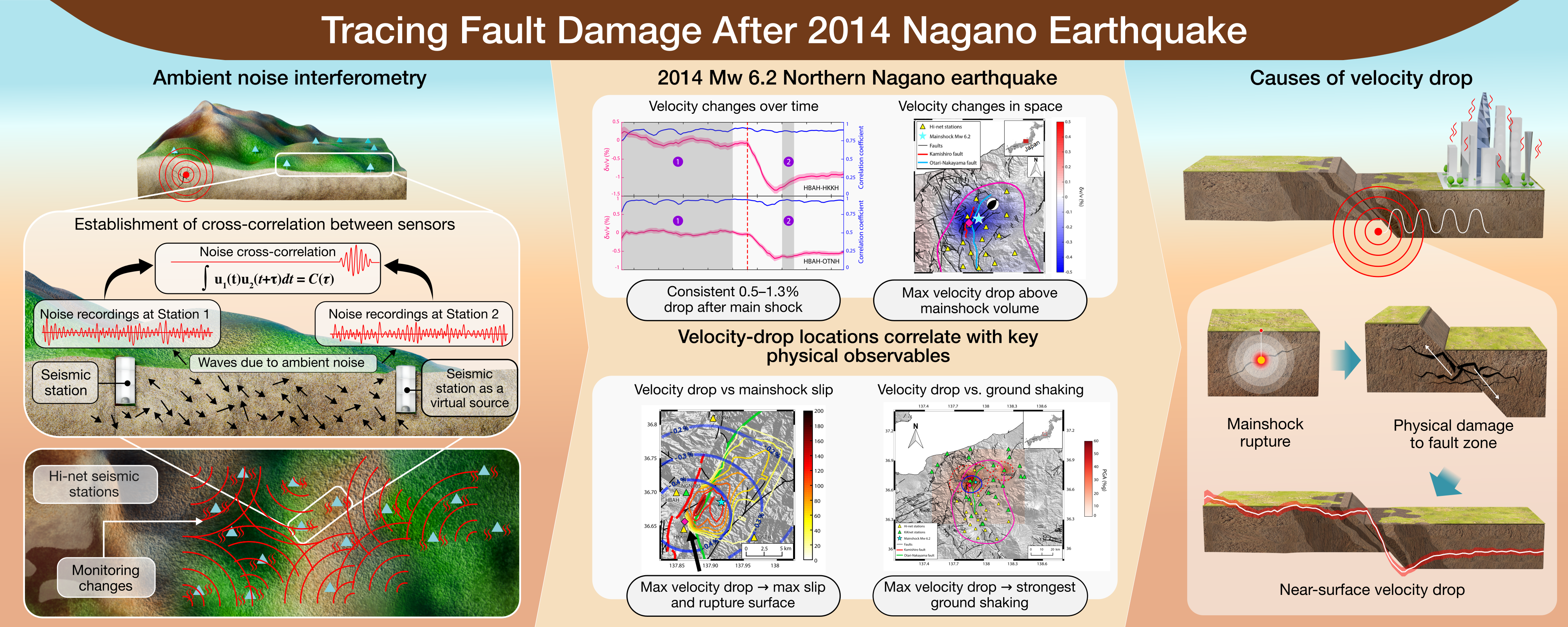

Our recent Nature Communications Earth and Environment paper, “Fault zone damage caused by the mainshock rupture during the 2014 Northern Nagano earthquake,” explores how the shallow crust responded to this event — not just at the surface, but also at depth. Using a technique called ambient noise interferometry, we uncovered how seismic waves slowed down by up to 1.3% in the crust after the earthquake, revealing zones where rocks had been damaged by the violent rupture.

Earthquakes produce sudden, violent shaking, but the Earth is never still it’s constantly vibrating. These tiny, persistent vibrations — generated by ocean waves, wind, and human activity — form what we call ambient seismic noise.

By analyzing how surface waves generated by this background ambient noise travel between seismic stations, we can “listen” for tiny changes in the subsurface. By cross-correlating the continuous noise recordings from pairs of stations, we effectively recreate how seismic waves would have traveled between them — even without any earthquake.

This method, known as ambient noise interferometry, enables us to track small changes in the Earth’s seismic velocity — an indicator of the stiffness or damage of rocks.

The first challenge lies in the nature of ambient noise itself: it is extremely complex. Fluctuations caused by weather, human activity, or even recording instruments can easily mask the subtle signals we aim to detect. To overcome this, we processed three months of continuous recordings from 27 seismic stations across the Nagano region, carefully filtering and stacking the data to strengthen the correlations between signals. Gradually, a clear pattern emerged — a consistent velocity drop of about 0.5–1.3% after the mainshock.

But measuring that the velocity changed was only the first step — the real challenge was understanding where and why it changed. Detecting a velocity drop alone tells us little; to link it to physical processes such as fault-zone damage or near-surface shaking, we needed to pinpoint its exact location in the crust. This became our second challenge: mapping the geometry of the velocity changes to uncover their cause.

We developed an approach to locate where in the crust those changes occurred. By combining information from hundreds of station pairs, we reconstructed the spatial pattern of velocity variations — effectively mapping where the crust had been most altered. This revealed that the velocity drop was concentrated near the mainshock area, within the upper two kilometers of the crust. The strongest reductions matched the fault’s surface rupture and the zones of maximum slip — the portion of the fault that moved the most during the earthquake, where the crust broke and slid by more than a meter.

This coherence was no coincidence. The areas that experienced the largest velocity drop also corresponded to where the ground shaking was strongest, as shown by Japan’s strong-motion (PGA) network. Taken together, these observations indicate that the mainshock rupture physically damaged the fault zone, weakening the rocks and altering their elastic properties.

Beyond confirming that the mainshock damaged the fault zone, our work also shows what can be achieved when dense seismic networks and advanced processing are combined. By using hundreds of cross-correlations, we could visualize not just that the crust changed, but how, revealing patterns of weakening that follow the shape of the fault itself. This spatial detail turns ambient noise interferometry from a monitoring concept into a quantitative imaging tool. In the future, applying the same approach to other fault systems could help identify areas that remain mechanically weak after a major rupture, offering new ways to assess how energy is dissipated and how the crust heals over time.

The story of an earthquake doesn’t end when the shaking stops. The crust keeps evolving — fractured rocks relax, microcracks slowly close, and the damaged fault zone begins its long recovery. By monitoring how seismic velocity changes through time, we can watch this recovery unfold and gain insight into how faults weaken and heal. In the case of the Nagano earthquake, the clear spatial match between velocity drop, surface rupture, and strong shaking shows that both the rupture itself and the intense ground motion contributed to damaging the crust. Understanding this pattern is essential: such damage influences how stress is redistributed in the fault zone and can shape where aftershocks occur. Mapping these processes helps us capture the full life cycle of an earthquake — from rupture to recovery — and refine the models we use to assess seismic hazard.

For us, one of the most rewarding parts of this research was realizing how much information hides in what most people call “noise”. Without waiting for new earthquakes or using artificial sources, we could watch the crust evolve day by day — as if listening to the Earth’s slow recovery after the shock. This experience changed how we see seismic noise: not as background, but as a constant voice of the planet’s inner workings.

Our work is part of a growing effort to turn continuous, passive seismic monitoring into a tool for tracking fault damage in real time. In the future, this approach could allow scientists — and eventually civil protection agencies — to detect signs of weakening or healing soon after a major earthquake. Turning noise into knowledge, we move one step closer to understanding how the ground beneath us breathes, breaks, and heals.

Sometimes, listening quietly reveals more than waiting for the next big shake.

Further reading

-

Muzellec, T., De Landro, G., & Zollo, A. (2025). Fault zone damage caused by the mainshock rupture during the 2014 Northern Nagano earthquake. Communications Earth & Environment, 6(1), 934.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Sustainable agricultural practices

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jul 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in