Unpacking the Energy-Economy Puzzle: Does Cutting Energy Use Really Hurt Growth?

Published in Earth & Environment, Sustainability, and Economics

Have you ever wondered if using less energy could harm our economy? It’s a question that pops up a lot these days, especially as the world grapples with climate change and the push to reduce carbon emissions. Many people—and even some policymakers—assume that energy is the lifeblood of economic growth. They worry that cutting back on energy use might lead to job losses, lower living standards, and a weaker economy overall. But what if that’s not the whole story? What if reducing energy consumption doesn’t hurt as much as we think—and might even open doors to a greener future? That’s exactly what we set out to explore in our study.

Why We Wrote This Paper

The idea for this research came from a tug-of-war we’ve all heard about: economic growth versus environmental protection. On one hand, energy powers factories, homes, and businesses—everything that keeps a country humming. Politicians like U.S. Senators Rick Scott and Bill Cassidy have argued that cutting energy use could tank the economy and cost jobs. On the other hand, figures like Al Gore insist that businesses can adapt, and reducing fossil fuel use won’t spell disaster. Plus, with global warming knocking at our door, we only have one planet to work with. Countries often hesitate to join big environmental plans because they fear slowing their development. We wanted to dig into the data and see what’s really going on. Does slashing energy use actually harm economic performance, or is that fear overblown?

What We Did

To find out, we gathered data from 80 countries and 20 country groups—like high-income nations, middle-income ones, and regions like Sub-Saharan Africa or the European Union. We looked at yearly numbers from 1970 to 2014, focusing on energy consumption (measured as kilograms of oil equivalent per person) and economic performance (measured by Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, which is the total value of everything a country produces). We didn’t just lump all the data together; we analyzed it both globally and country-by-country to avoid missing the unique quirks of each place.

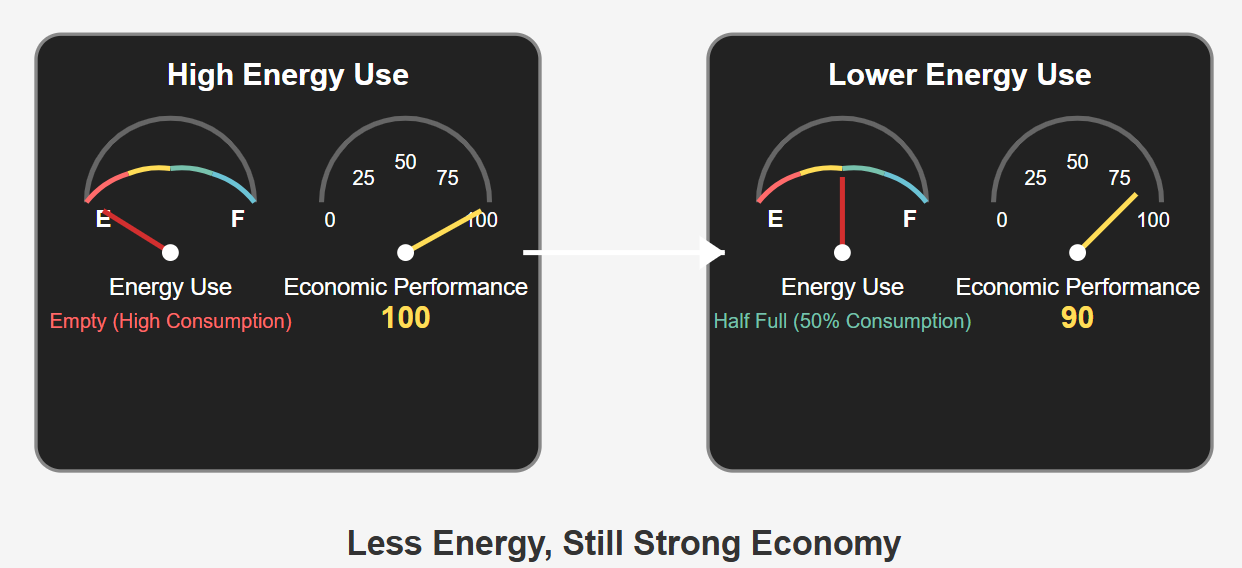

We used a fancy statistical tool called the Nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag model—NARDL for short. Don’t let the name scare you! It’s just a way to check if energy use affects the economy differently when it goes up versus when it goes down. Think of it like this: if you get a raise, you might spend more, but if your pay gets cut, you might not cut back as much because you’ve got savings or other tricks up your sleeve. We wondered if energy and GDP might work the same way—not a straight line, but a bit of a zigzag.

What We Found

Here’s the big takeaway: more energy use often boosts the economy, but cutting back doesn’t hurt as much as people fear. When countries ramp up energy consumption, their GDP tends to climb—makes sense, right? More energy means more production, more jobs, more activity. But when they dial it down, the drop in GDP isn’t nearly as dramatic. For many countries and groups, reducing energy use had little to no negative effect on their economies. This “asymmetric” pattern—where increases and decreases don’t mirror each other—was a key discovery.

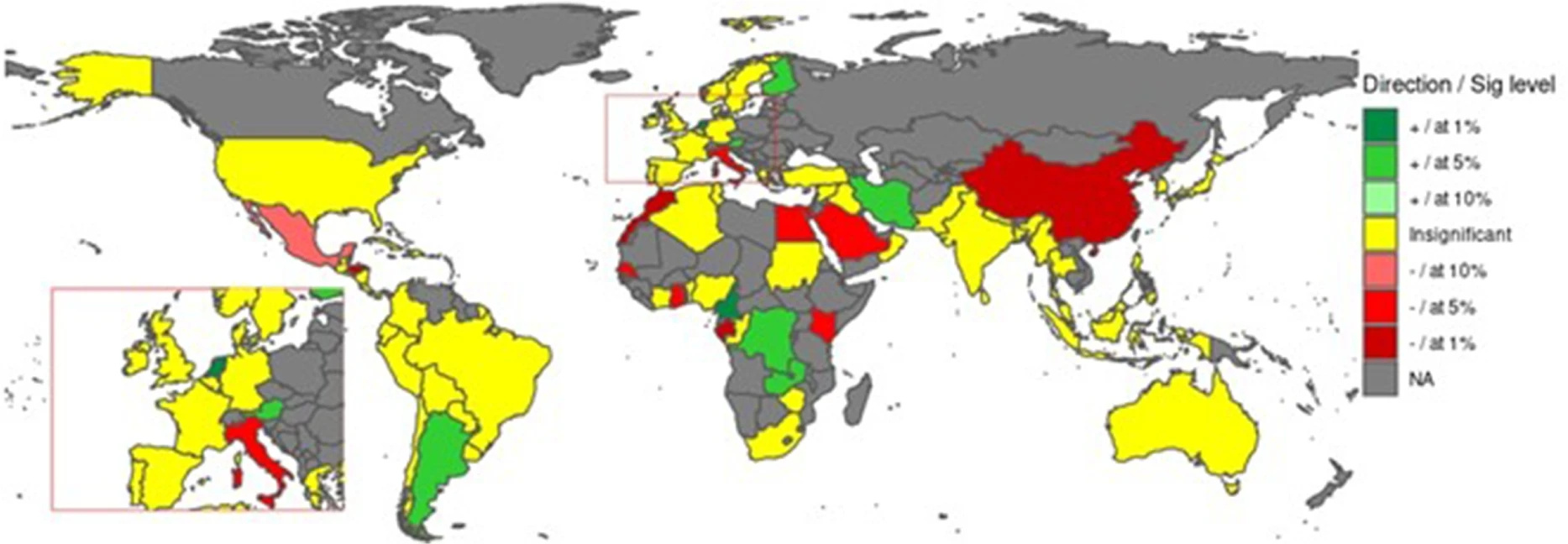

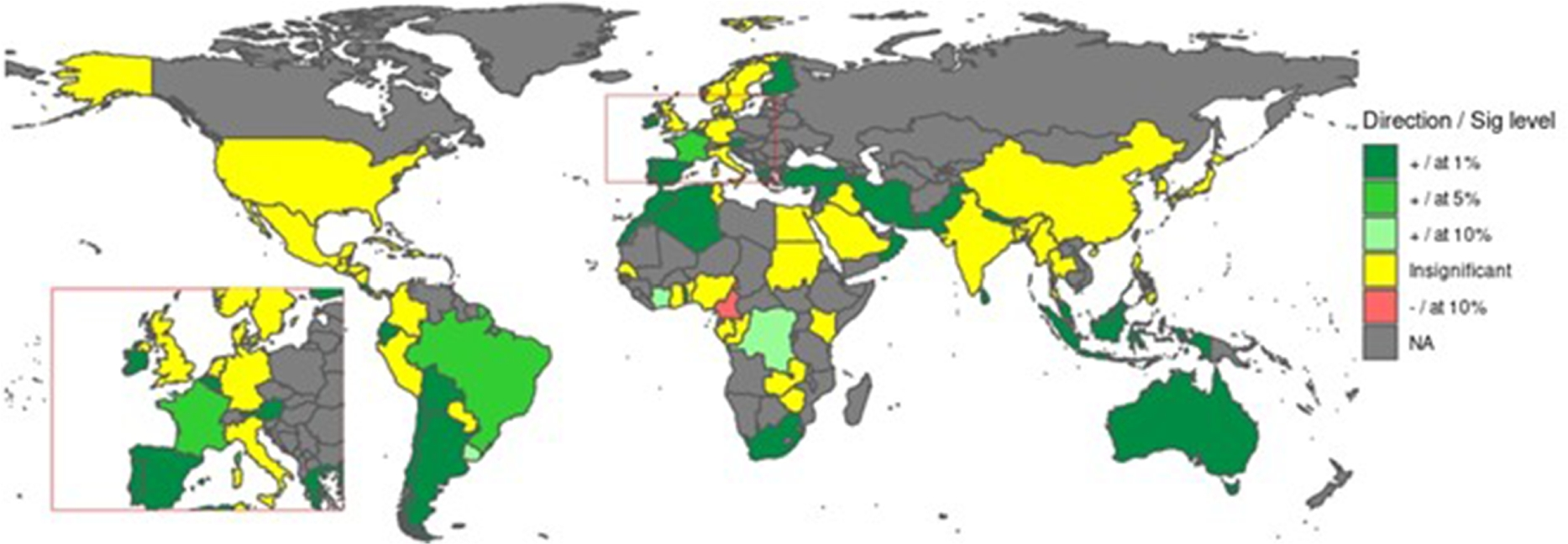

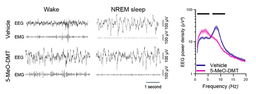

Take a look at this map from our study (Figure 2), which shows the impact of the decrease in the energy usage on countries’ GDP, NARDL model:

The colors tell the story: darker shades often mean a stronger link between energy use and GDP growth. But when we dug deeper with our NARDL model, we saw that decreasing energy use didn’t tank economies the way increasing it boosted them. For example, in OECD countries (think wealthy nations like the U.S. and Germany), more energy meant more growth, but less energy didn’t mean a big slump. The same held true for upper-middle-income countries.

Globally, the picture was fuzzier—mixing all countries together didn’t show a clear link. But when we zoomed into specific nations and groups, the patterns popped out. This tells us that every country’s story is a little different, shaped by its economy, geography, and energy habits.

Why This Matters

This finding flips a common worry on its head. If cutting energy use doesn’t hit GDP hard, it’s a green light for sustainability efforts. Imagine this: countries could trim fossil fuel use, ramp up renewables, and fight climate change—without crashing their economies. It’s not just about surviving; it’s about thriving in a cleaner world. Governments could offer incentives for energy-efficient tech or rules to curb waste, knowing the economic fallout might be minimal.

The Nitty-Gritty (Made Simple)

Our NARDL model let us split energy changes into “ups” and “downs.” We found that “ups” (more energy) often lifted GDP, while “downs” (less energy) didn’t drag it down much. This asymmetry is a big deal because it challenges the old-school idea that energy and growth are locked together like dance partners. Instead, it’s more like a flexible friendship—sometimes they move together, sometimes they don’t.

Of course, our study isn’t perfect. The data stops at 2014, so we’re missing recent shifts like the rise of solar power or electric cars. Plus, we used yearly numbers—monthly or quarterly data might reveal more twists. Future research could fill those gaps, but for now, we’ve got a solid starting point.

What’s Next?

So, what do you think? Could cutting energy use spark innovation—like better renewable tech or smarter energy habits—without hurting the economy? Or are there hidden catches we haven’t spotted yet? Our study suggests that energy conservation isn’t the economic boogeyman it’s made out to be. For policymakers, this could mean bolder steps toward sustainability without the fear of stunting growth.

Follow the Topic

-

Energy Efficiency

This journal covers topics related to energy efficiency, savings, consumption, sufficiency, and transition in all sectors across the globe. Areas of current interest include:

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Sustainable Development Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Papers from the 12th International Conference on Energy Efficiency in Domestic Appliances and Lighting (EEDAL’24)

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in