Urban Footprints: Assessment of Urban Walkability and Thermal Comfort in a Changing Climate

Published in Earth & Environment, Sustainability, and Arts & Humanities

Sometimes, while walking one path in your journey, you discover something entirely different from what you set out to find.

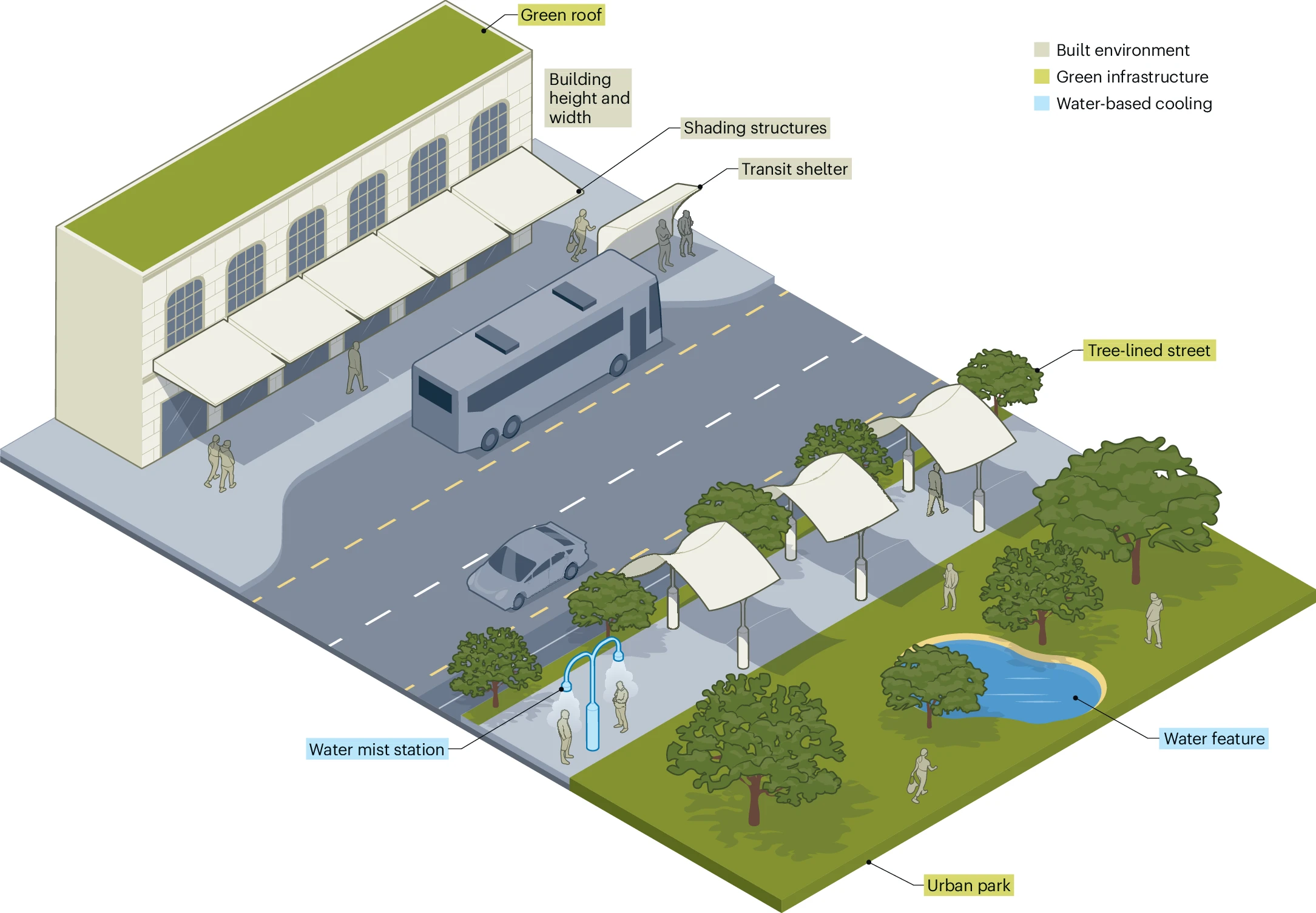

The journey of this paper began with an exploration of the various ways walkability can be assessed as transportation systems shift their trajectory to foster more sustainable modes of transportation. We examined various criteria and numerous indices—what if we enhance the sidewalks, curbs, street signage, and aesthetics? What about improving density and accessibility so it’s convenient to get from one place to another within a reasonable time? How about improving safety? Each time we listed an improvement in the context of Saudi Arabia, we ran into the same barrier: High temperatures.

No matter how well we enhance sidewalks, improve street features, or ensure safe and accessible routes, the extreme heat remains an unavoidable challenge. Even the most well-equipped infrastructure cannot support walkability if people cannot tolerate the outdoor temperatures. Without suitable weather conditions, active mobility, particularly walking, will remain limited, regardless of the quality of the physical environment.

This stage of the journey led us to take a closer look at how weather shapes walkability, how it can restrict it, and to what extent. We examined the available approaches used by different studies to measure these impacts, and as we delved deeper, it became clear that the challenge ahead is only growing. Looking toward the future, we found that with climate change accelerating, extreme temperatures are expected to become more frequent and intense, placing even greater limits on walkability.

Climate change is not only raising global temperature, but also amplifying the frequency, intensity, duration, and unpredictability of heat events. In regions like the Arabian Peninsula where summers are already extreme, even a small increase in temperature can significantly reduce the number of safe and comfortable hours outdoors. This means that the window for engaging in outdoor activities, including walking, will continue to shrink, and urban spaces designed for active mobility may go underused.

Once we understood the magnitude of the threat, we chose to focus on one of the most pressing extreme weather conditions: extreme heat. We explored the unique challenges it presents and the methods available to quantify it. Through this lens, we discovered how closely the willingness to remain outdoors and engage in physical activity is tied to thermal comfort, a state shaped by the interplay of physiological, physical, and psychological factors. Each of these has its own parameters and measurement methods, providing a more complete understanding of how much the human body can endure when confronted with soaring temperatures.

The next step in our journey was to explore how cities can adapt to the rising threat of extreme heat through changes in urban form and the implementation of climate-resilient adaptation strategies. If the weather itself is the barrier, then how can we design our streets, our buildings, and our open spaces to protect people from its effects? We began by looking at adaptation strategies through the lens of urban morphology, asking: What if we reimagine the built environment so that it works with the climate rather than against it? What if we integrate greenery, shade, and cooling elements into the very fabric of the city? Could we create outdoor spaces where walking remains comfortable, even under extreme conditions?

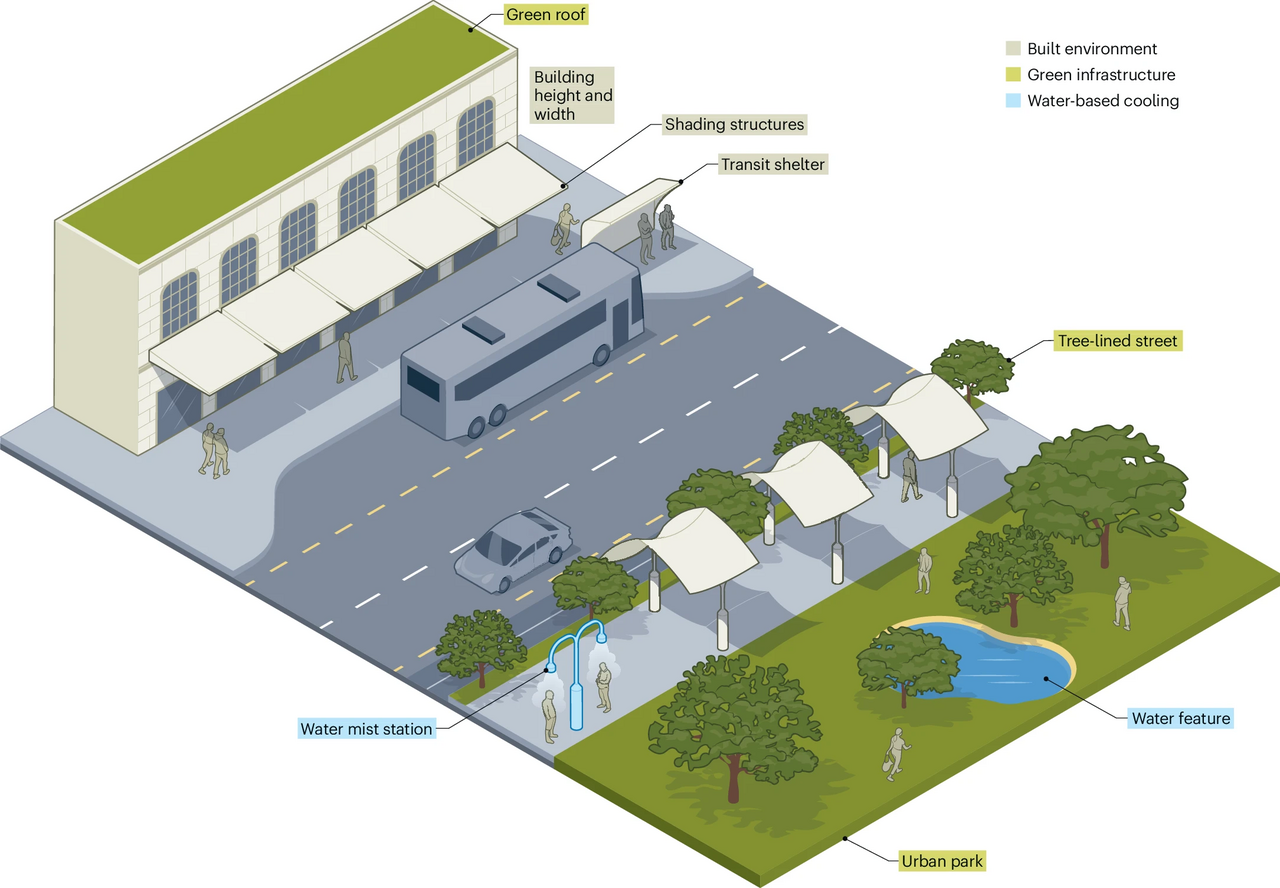

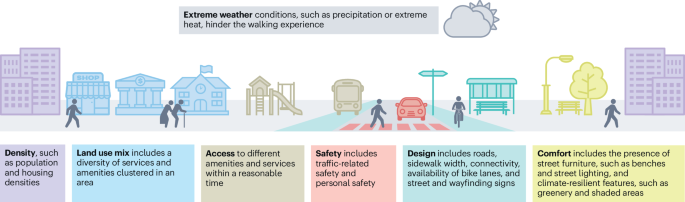

We found that adaptation strategies fall broadly into three categories: built infrastructure, green infrastructure, and water-based cooling. Built solutions—such as pedways, shadeways, and pergolas—can dramatically reduce heat exposure by blocking solar radiation, while compact urban forms and deep street canyons shield pedestrians from direct sun, lowering peak temperatures by significant margins. Green infrastructure, from tree canopies to green facades and urban parks, adds shade, cools surfaces, and improves comfort through evapotranspiration, with its effectiveness shaped by placement, density, and integration with wind corridors. Water-based strategies, including mist stations and water features, can deliver refreshing microclimates, with mist systems in hot, arid areas reducing perceived temperatures significantly during peak heat.

Through this exploration, we saw that no single solution works in isolation. The most effective outcomes emerge when urban geometry, vegetation, and cooling technologies are combined and tailored to local conditions. Yet, we also recognized that these ideas face real-world barriers: limited budgets, fragmented policies, and the need for strong community and political support. Tools such as the Cool Walkability Index and the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ can help cities identify where protection is lacking and where interventions will have the greatest impact. Ultimately, adapting urban morphology is not just about altering the city’s form—it is about reshaping it so that, even in a warming world, walking remains not only possible but enjoyable.

In the end, our exploration of walkability in the face of extreme heat was never just about sidewalks, shading, or cooling strategies. It was about reimagining cities so that people can thrive outdoors, even as the climate shifts around them. The path forward will require innovation, collaboration, and an unwavering commitment to designing spaces that are as resilient as inviting. Because in the cities of tomorrow, the true measure of success will not only be how far we can walk, but how much we want to.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Cities

This journal aims to deepen and integrate basic and applied understanding of the character and dynamics of cities, including their roles, impacts and influences — past, present and future.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in