What comparative genomics taught us about the vaginal commensal Lactobacillus crispatus

Published in Microbiology

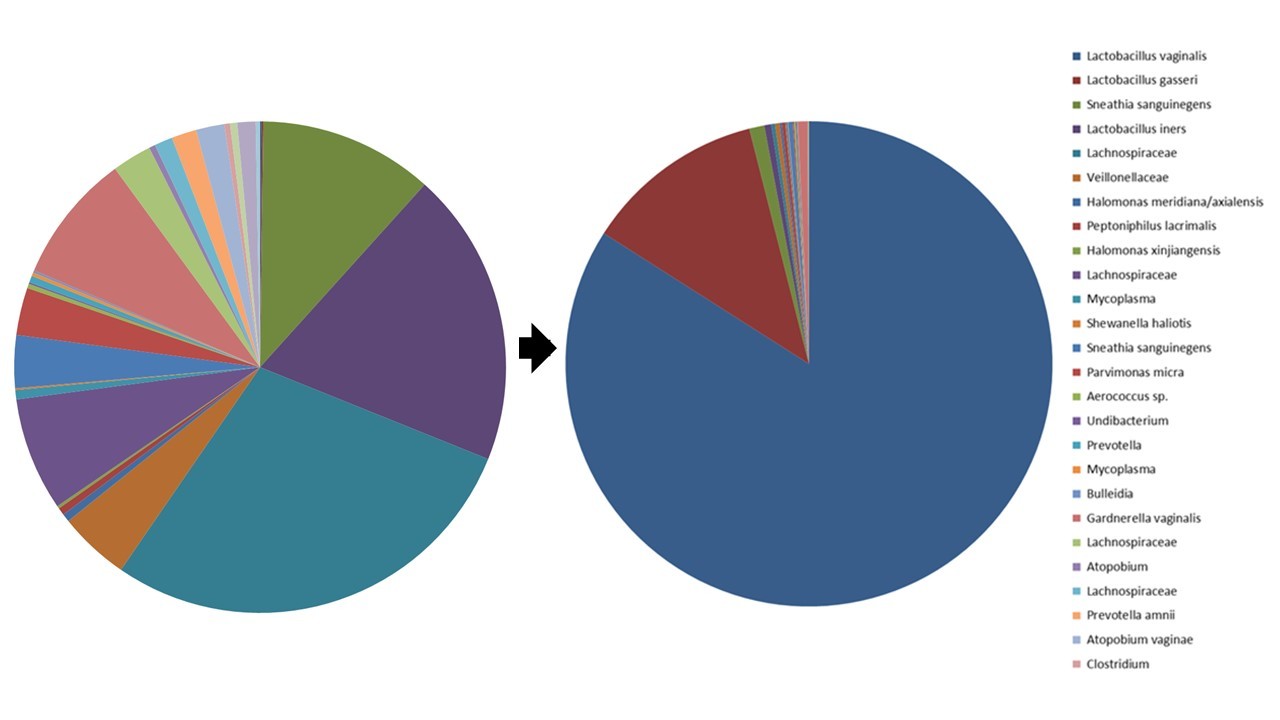

Well, by the use of cultivation techniques, my research team was able to demonstrate the transition from a dysbiotic vaginal microbiota (DVM) obtained from a vaginal swab to a ‘healthy’ bacterial community dominated by lactobacilli (LVM). A dysbiotic vaginal microbiota, also known as bacterial vaginosis (BV), is a highly diverse bacterial population depleted from Lactobacillus. Bacterial vaginosis is associated with an increased risk for sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, decreased fertility rates, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. All we need to do next is to disperse the obtained population of vaginal bacteria – note this well - the woman’s own bacteria into a vaginal gel and use this for a personalised BV-treatment.

Too good to be true? The first cracks appeared when I was drinking a cocktail on the roof garden after my talk at the conference reception and an expert in the field approached me. ‘Very nice story’, he said, ‘but your idea will never work’. I swirled the content of my glass as if the sound generated by the ice blocks in my cocktail would act as some kind of spell to blow away his last words. He continued ‘The lactobacilli you are cultivating from the host have lost the ability to dominate the microbial population. The problem is in their genes. Their population will never sustain in vivo’. I took another sip of my Martini on the rocks and assured the expert that I was definitely going to look into this. And so we did. In the laboratory, we selected Lactobacillus crispatus strains from a dysbiotic vaginal microbiota (DVM) and Lactobacillus dominated microbiota (LVM) and systematically checked for differences in the two groups of strains by comparative genomics.

What appeared to be the case? To our big surprise this was not about LVM-strains losing a genetic property, it was about the DVM-strains gaining one. We found a novel glycosyltransferase gene that was more prevalent among strains isolated from DVM. All speculation at this point, nonetheless this could indicate that, as the vaginal niche in a dysbiotic state is under immune pressure, this gene mediates variation in cell surface glycoconjugates. In other words, this gene encodes for the ability of Lactobacillus crispatus to change its coat making the bacterium invisible to the immune system. A selective advantage for survival under these conditions. Thus, if this appears to be true, the expert is half right. Simple enrichment by cultivation in the lab will not work. We will need to deliberately select for L. crispatus strains containing the glycosyltransferase gene allowing the transition from an inflammatory state of bacterial vaginosis to a Lactobacillus-dominated state. This new insight resulted from a clever comment by an expert at a conference five years ago and the fantastic effort of the researchers who took part in this investigation. Our research appeared in the open access journal Microbiome earlier this week.

Reference

Kort R. Personalized therapy with probiotics from the host by TripleA. Trends Biotechnol. 2014 Jun;32(6):291-3. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.04.002.

Follow the Topic

-

Microbiome

This journal hopes to integrate researchers with common scientific objectives across a broad cross-section of sub-disciplines within microbial ecology. It covers studies of microbiomes colonizing humans, animals, plants or the environment, both built and natural or manipulated, as in agriculture.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Harnessing plant microbiomes to improve performance and mechanistic understanding

This is a Cross-Journal Collection with Microbiome, Environmental Microbiome, npj Science of Plants, and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes. Please click here to see the collection page for npj Science of Plants and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes.

Modern agriculture needs to sustainably increase crop productivity while preserving ecosystem health. As soil degradation, climate variability, and diminishing input efficiency continue to threaten agricultural outputs, there is a pressing need to enhance plant performance through ecologically-sound strategies. In this context, plant-associated microbiomes represent a powerful, yet underexploited, resource to improve plant vigor, nutrient acquisition, stress resilience, and overall productivity.

The plant microbiome—comprising bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms inhabiting the rhizosphere, endosphere, and phyllosphere—plays a fundamental role in shaping plant physiology and development. Increasing evidence demonstrates that beneficial microbes mediate key processes such as nutrient solubilization and uptake, hormonal regulation, photosynthetic efficiency, and systemic resistance to (a)biotic stresses. However, to fully harness these capabilities, a mechanistic understanding of the molecular dialogues and functional traits underpinning plant-microbe interactions is essential.

Recent advances in multi-omics technologies, synthetic biology, and high-throughput functional screening have accelerated our ability to dissect these interactions at molecular, cellular, and system levels. Yet, significant challenges remain in translating these mechanistic insights into robust microbiome-based applications for agriculture. Core knowledge gaps include identifying microbial functions that are conserved across environments and hosts, understanding the signaling networks and metabolic exchanges between partners, and predicting microbiome assembly and stability under field conditions.

This Research Topic welcomes Original Research, Reviews, Perspectives, and Meta-analyses that delve into the functional and mechanistic basis of plant-microbiome interactions. We are particularly interested in contributions that integrate molecular microbiology, systems biology, plant physiology, and computational modeling to unravel the mechanisms by which microbial communities enhance plant performance and/or mechanisms employed by plant hosts to assemble beneficial microbiomes. Studies ranging from controlled experimental systems to applied field trials are encouraged, especially those aiming to bridge the gap between fundamental understanding and translational outcomes such as microbial consortia, engineered strains, or microbiome-informed management practices.

Ultimately, this collection aims to advance our ability to rationally design and apply microbiome-based strategies by deepening our mechanistic insight into how plants select beneficial microbiomes and in turn how microbes shape plant health and productivity.

This collection is open for submissions from all authors on the condition that the manuscript falls within both the scope of the collection and the journal it is submitted to.

All submissions in this collection undergo the relevant journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief of the relevant journal. As an open access publication, participating journals levy an article processing fee (Microbiome, Environmental Microbiome). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief of the journal where the article is being submitted.

Collection policies for Microbiome and Environmental Microbiome:

Please refer to this page. Please only submit to one journal, but note authors have the option to transfer to another participating journal following the editors’ recommendation.

Collection policies for npj Science of Plants and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes:

Please refer to npj's Collection policies page for full details.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Microbiome and Reproductive Health

Microbiome is calling for submissions to our Collection on Microbiome and Reproductive Health.

Our understanding of the intricate relationship between the microbiome and reproductive health holds profound translational implications for fertility, pregnancy, and reproductive disorders. To truly advance this field, it is essential to move beyond descriptive and associative studies and focus on mechanistic research that uncovers the functional underpinnings of the host–microbiome interface. Such studies can reveal how microbial communities influence reproductive physiology, including hormonal regulation, immune responses, and overall reproductive health.

Recent advances have highlighted the role of specific bacterial populations in both male and female fertility, as well as their impact on pregnancy outcomes. For example, the vaginal microbiome has been linked to preterm birth, while emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota may modulate reproductive hormone levels. These insights underscore the need for research that explores how and why these microbial influences occur.

Looking ahead, the potential for breakthroughs is immense. Mechanistic studies have the power to drive the development of microbiome-based therapies that address infertility, improve pregnancy outcomes, and reduce the risk of reproductive diseases. Incorporating microbiome analysis into reproductive health assessments could transform clinical practice and, by deepening our understanding of host–microbiome mechanisms, lay the groundwork for personalized medicine in gynecology and obstetrics.

We invite researchers to contribute to this Special Collection on Microbiome and Reproductive Health. Submissions should emphasize functional and mechanistic insights into the host–microbiome relationship. Topics of interest include, but are not limited to:

- Microbiome and infertility

- Vaginal microbiome and pregnancy outcomes

- Gut microbiota and reproductive hormones

- Microbial influences on menstrual health

- Live biotherapeutics and reproductive health interventions

- Microbiome alterations as drivers of reproductive disorders

- Environmental factors shaping the microbiome

- Intergenerational microbiome transmission

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 16, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

The glycosyltransferase could also change phage sensitivity

Yes, excellent idea. Could be very interesting to have a look the role of bacteriophages in a student project - would be willing to share the strains (and source of bacteriophages).