What do play-fighting and pessimism tell us about pain in calves?

Published in Zoology & Veterinary Science and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

On commercial farms, it’s common practice to prevent horns from developing by burning the horn buds with a hot iron. Even when pain control is applied, it’s highly likely that they experience significant pain in the hours and days following the procedure. However, asking how calves feel after disbudding is challenging, especially because they may have evolved to hide their pain.

What does calf play say about pain?

Imagine a group of preschoolers in the playground; you might see some playing tag, while others are rough-and-tumble wrestling. Calves are the same – they run alone, they run together, they jump, they kick, and they play-fight. One way to ask a calf about pain is to observe their play, assuming that the less they play, the worse they feel.

Two calves engaging in play-fighting. Image made with ChatGPT (OpenAI).

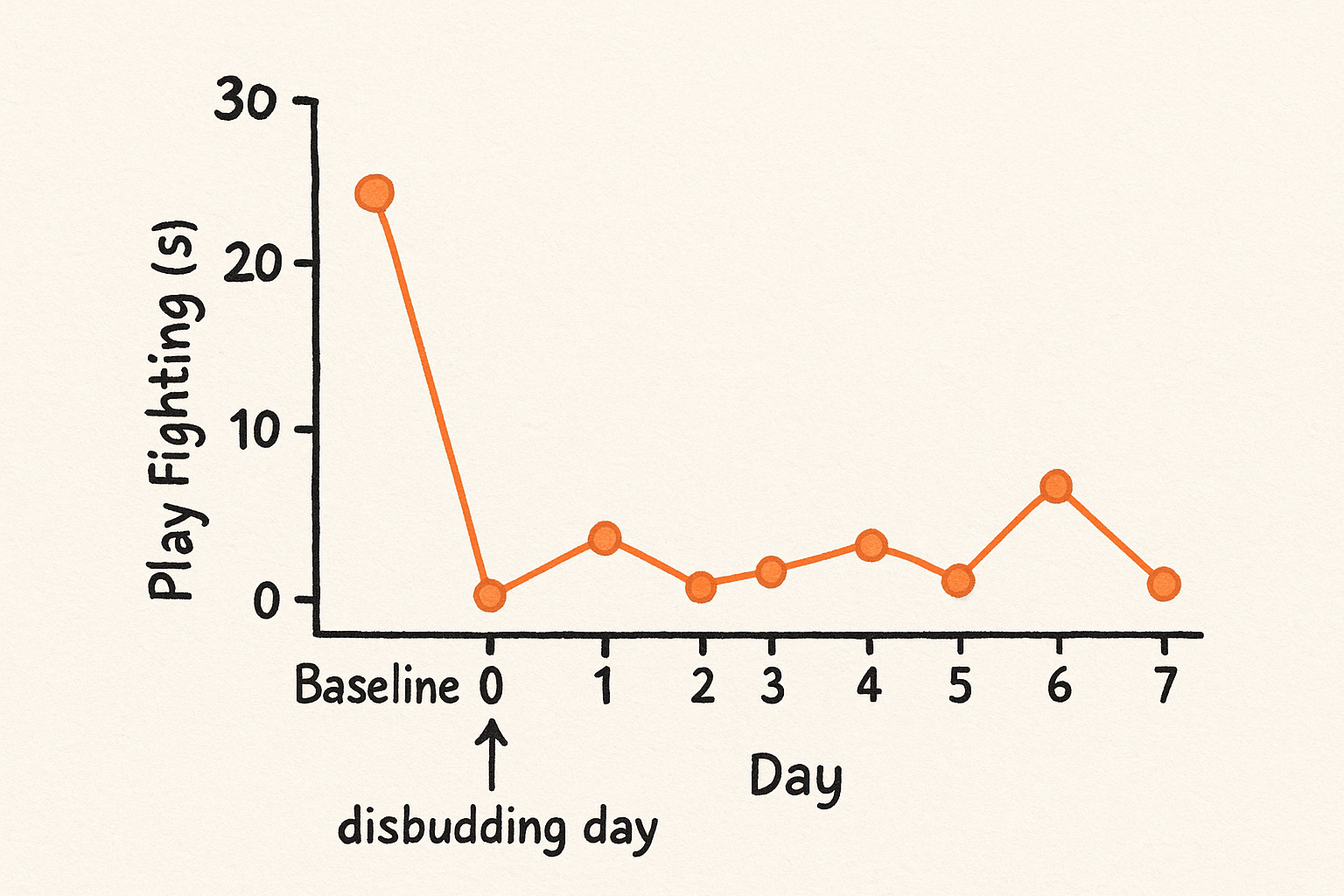

In this study, after disbudding, the calves kept running around, but play-fighting was almost eliminated over the next 7 days. Why? Looking at how calves play-fight, this makes sense – calves might avoid banging heads if the disbudding injury is still painful even about 7 days post-disbudding. Or perhaps it hurt once, and they become afraid of play-fighting altogether.

Changes in play-fighting duration from “baseline” (before disbudding) to 7 days after disbudding (seconds of play-fighting per 4 hour daily observation). Adapted from Figure 1 in the paper (doi: 10.1007/s44338-025-00105-7) using ChatGPT (OpenAI).

Is the bucket of milk half empty?

So, calves feel pain after disbudding, but just like people, they likely all handle it differently. This can be related to whether your glass (or bucket of milk) is half full or half empty. Like humans, more pessimistic calves may expect pain to be worse and end up experiencing it more negatively.

All calves, whether pessimist or optimist, stopped play-fighting after disbudding. On the other hand, most of them actually ran around more than before on the day after disbudding, potentially to make up for the lost play-fighting or to cope with stress. But what about the pessimistic ones? They didn’t show quite the same increase in running, suggesting they weren’t recovering in the same way or not at the same pace.

Next steps?

Implication 1: Better or longer pain relief needs to be explored for calves after disbudding.

If calves don’t play-fight for up to a week after disbudding, this likely tells us that they need better pain relief. Unlike us, they can’t reach for paracetamol themselves, so more research is needed on the best schedules of pain treatment to ensure they are free from pain and can play with their friends.

Implication 2: More pessimistic calves may have worse or longer-lasting experiences of pain

It’s easy to accept that “one size doesn’t fit all” for humans, and this idea needs to be extended to non-human animals like calves. We need to better understand how each calf experiences pain so that we can tailor their care to them, much like we would try to do with patients in a hospital.

Interested in the interplay between pain, play, and pessimism in calves? Read the full paper here.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Animals

This is a fully open access, peer-reviewed journal that supports multidisciplinary research across all fields related to animal science, including animal health, behavior, physiology, ecology and more.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Recent Progress in Gut Microbiome Research for Animal Health and Production

Microbial populations throughout the gastrointestinal tract, from the foregut to the hindgut, play essential roles in host metabolism, immune modulation, nutrient absorption, and overall physiological performance. Recent scientific advances have revealed the complexity and functional importance of these microbial ecosystems, particularly in livestock and companion animals. This Collection invites original research and critical reviews that explore the diversity, function, and modulation of gastrointestinal microbiota and their implications for animal health, productivity, and sustainable agriculture. We welcome submissions examining the impact of probiotics, prebiotics, phytobiotics, and dietary interventions on microbial structure and activity across the digestive system, including the rumen in ruminants. Of special interest are studies addressing how microbiota regulate host metabolic pathways, influence energy utilization, and affect nutrient-sensing and immune signaling.

Research employing high-throughput and integrative omics approaches, including metabolomics, transcriptomics, metagenomics, and nutrigenomics, is highly encouraged. These tools enable deeper insights into microbial functions, microbial-host cross-talk, and regulatory mechanisms underlying metabolic adaptation and health outcomes. This Collection also emphasizes applications relevant to sustainable animal production, including reduced reliance on antimicrobials, improved feed efficiency, and mitigation of environmental impacts such as methane emissions. Cross-species comparisons and models that connect microbiome function with genetic, nutritional, and environmental factors are also welcome.

Keywords: gastrointestinal microbiome, rumen microbiota, microbial-host interactions, immune modulation, omics technologies

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 03, 2026

Animal Habitats in a Changing World: Adaptation, Conservation, and Interactions Across Ecosystems

The natural world is undergoing unprecedented changes due to climate change, habitat loss, and increasing human influence. This Collection aims to gather interdisciplinary research on animal adaptation, biodiversity responses, and conservation strategies for animals and their habitats in a rapidly changing world. We welcome contributions related to animal habitats covering behavioral ecology, genetics, physiology, conservation management, wildlife-human interactions, and novel methodological approaches in animal science.

Keywords: Animal habitat, Animal adaptation, Evolution, Genetic divergence, Biodiversity conservation, Ecosystem interactions, Climate Change, Wildlife management

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Sep 09, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in