What I Didn’t Expect When I Started My Research Journey

Published in Research Data and Public Health

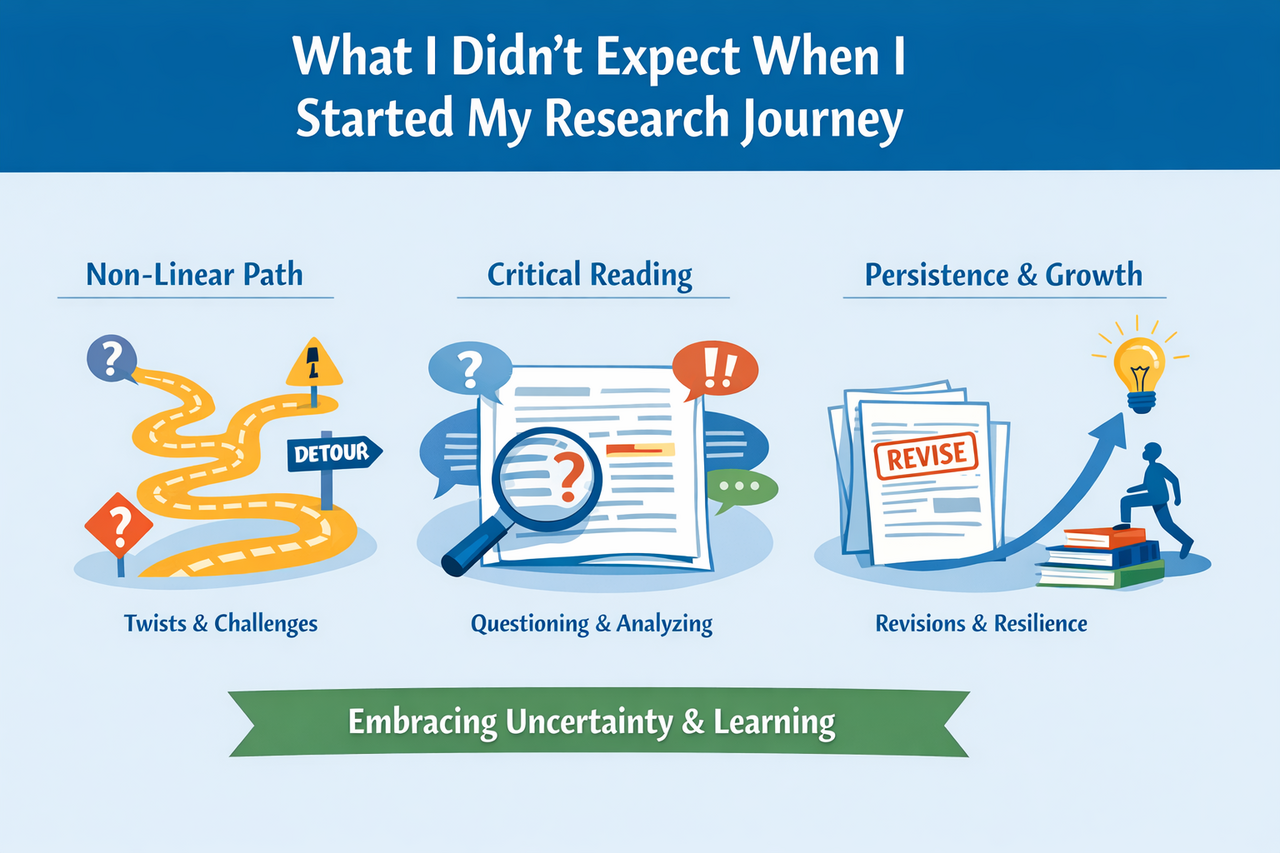

One of the first surprises was how non-linear the research process can be.

Early on, I assumed progress would follow a logical sequence from question to data to conclusions. In practice, research rarely moves in a straight line. Questions evolve as new information emerges, methods need revision, and initial assumptions are often challenged by the data itself. At times, this felt unsettling, particularly when effort did not immediately translate into visible outcomes. Over time, I learned that this uncertainty is not a sign that something has gone wrong, but an inherent part of producing careful and meaningful research.

Another unexpected lesson was the importance of critical reading.

At the beginning of my research journey, reading papers felt like an exercise in gathering information. I focused mainly on results and conclusions, often taking them at face value. As I gained experience, I realised that this approach was limiting. True engagement with the literature requires questioning how studies are designed, why specific methods are chosen, and how confidently conclusions are supported by the data. This shift changed how I read research and made me more reflective when designing and interpreting my own studies.

What surprised me most was how long it took to develop this way of thinking.

Critical reading did not come from a single course or guideline, but from repeated exposure, mistakes, and discussion. There were moments when revisiting the literature felt overwhelming, especially when studies conflicted or lacked transparency. Learning to sit with that discomfort, rather than rushing to simple answers, became an important part of my development as a researcher. Similar experiences have been described among early career researchers, where uncertainty is often present even when formal training has been strong (Melander et al., 2025).

I was also unprepared for how much persistence research demands.

Writing rarely ends with a first draft. Manuscripts go through multiple rounds of revision, feedback can be demanding, and rejection is a routine part of academic life. Early on, these experiences felt discouraging, and at times I questioned whether struggling meant I was falling behind. With time, I came to see these moments differently. Each revision clarified my thinking, and each critique improved the quality of the work. Learning to separate personal confidence from academic feedback was an important step in developing resilience.

Perhaps the most valuable lesson was realising that research is not only about producing results, but about developing a mindset. Patience, adaptability, and openness to critique matter as much as technical skills. I wish I had known earlier that struggling with uncertainty is not a weakness. It is often a sign that deeper learning is taking place and that important questions are being asked.

For early career researchers, this has become my main takeaway. Difficulty and uncertainty are not indicators of failure. They are part of the process of becoming a thoughtful and capable researcher. Accepting this early can make the research journey not only more manageable, but also more meaningful.

References

Melander C, Löfqvist C, Haak M, Smedegaard Bengtsen SE, Edgren G, Iwarsson S. Well prepared yet uncertain: Experiences of the early career transition after affiliation with an interdisciplinary graduate school. PLOS ONE. 2025.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0321039

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in