What Working Across Multiple Studies Taught Me About Evidence in Public Health Research

Published in Public Health

Working Across Multiple Studies: Reflections on Evidence in Public Health Research

When I first started out as an early career researcher, most of my attention was focused on individual studies. Each project felt self-contained. I concentrated on refining research questions, analysing data carefully, and presenting results as clearly as possible. Success, at that stage, meant completing a study and producing findings that appeared coherent and defensible on their own. It was only later, when I began working across multiple studies, that I started to see how public health evidence is built collectively, and how complex that process can be.

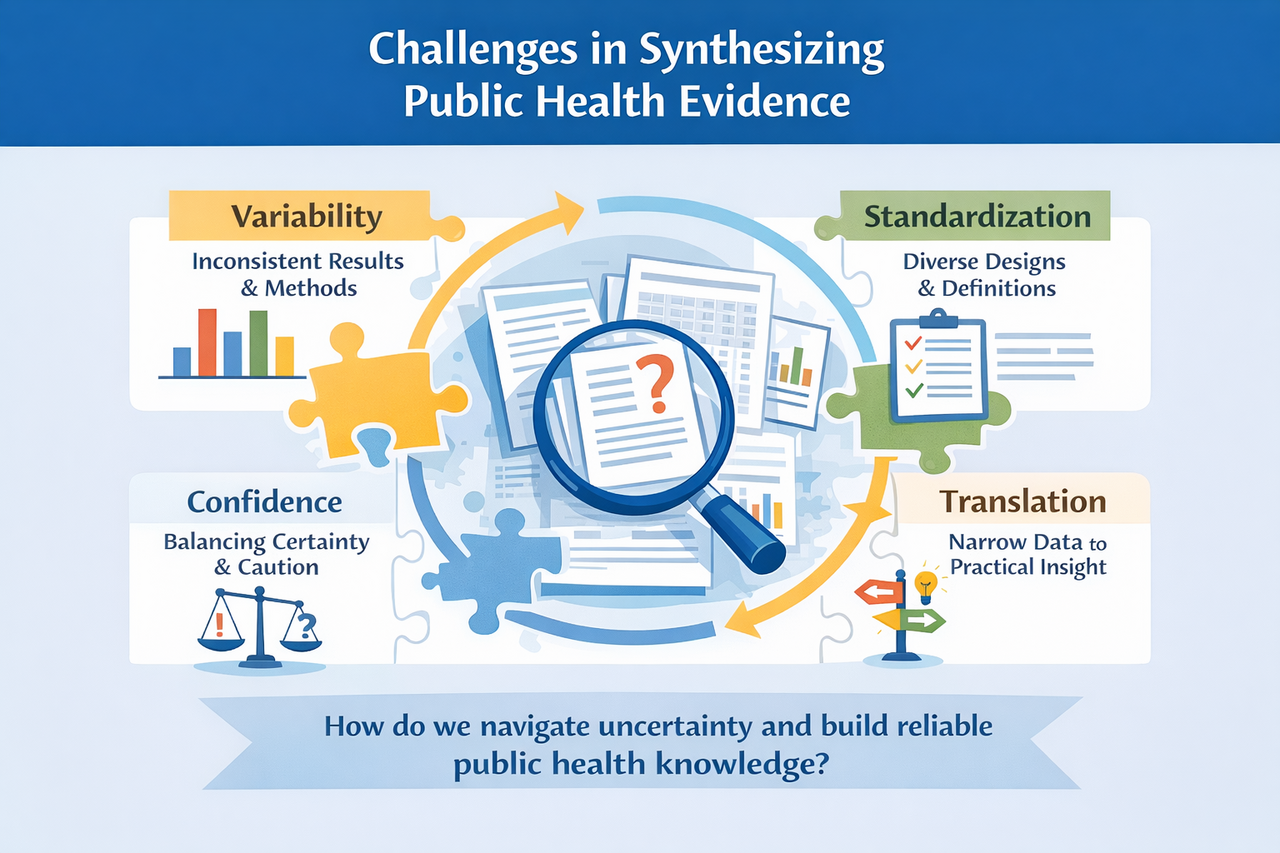

One of the first things that became clear was how much variability exists across studies.

On the surface, many projects appear to be asking similar questions, yet their findings can differ substantially. Differences in study design, diagnostic criteria, sampling approaches, and reporting practices all contribute to this variation. At first, these inconsistencies felt confusing and, at times, frustrating. I remember expecting that similar questions would naturally lead to similar answers. When they did not, I initially assumed that something must be wrong with one of the studies. Over time, I came to understand that variability is not simply a problem to be resolved, but an important part of interpreting research responsibly.

Working with systematic reviews and analytical studies made this even more apparent. I began to see how fragmented the evidence base can be when studies are not closely aligned. Individual studies often provide valuable insights within specific populations or settings, but their conclusions do not always translate easily beyond those contexts. This experience taught me to be much more cautious about generalization. I found myself asking different questions than before, not only what the results showed, but also where, how, and under what assumptions those results were produced. Evidence synthesis can help bring findings together, but it also highlights gaps in data quality and consistency that limit how confidently broader conclusions can be drawn.

This became particularly clear in my own work on a systematic review and meta-analysis examining the prevalence of vector-borne infections in dogs, where substantial variation in diagnostic methods and reporting across studies directly affected prevalence estimates and interpretation. Engaging with this literature reinforced how synthesis methods can both clarify broader patterns and expose important limitations in the underlying evidence base (Abdous et al., 2023).

Another challenge I did not fully anticipate was translating research findings into meaningful public health insight.

Quantitative results alone rarely provide clear guidance for prevention strategies or policy decisions. Early in my research journey, I tended to assume that strong numerical associations would naturally lead to clear recommendations. In practice, this was rarely the case. Making sense of results requires attention to ecological, behavioural, and health system factors that shape health outcomes. Without this broader perspective, there is a risk of oversimplifying complex public health problems. This realisation changed how I approached my own work, encouraging me to look beyond statistical results and think more carefully about context and real-world relevance.

Perhaps the most important lesson from working across multiple studies has been the sense of responsibility that comes with producing and communicating evidence. Public health research informs clinical decisions, surveillance priorities, and how risk is perceived by both professionals and the public. I became more aware of how easily certainty can be overstated, particularly when findings are taken out of context or presented without sufficient discussion of limitations. I learned that being clear about uncertainty does not weaken research. In my experience, it strengthens credibility and trust, especially when research findings may influence decision-making beyond academic settings.

For those at an early stage of their research careers, working across multiple studies can be an eye-opening experience. Differences between studies are not something to move past quickly, but something worth paying attention to. They often reveal why findings do not align as neatly as expected and highlight the importance of methodological choices that might otherwise be overlooked.

Over time, I learned to slow down when interpreting results and to think more carefully about context, populations, and underlying assumptions. Numbers alone rarely tell the full story. Understanding the ecological and system-level factors behind them is often where the most meaningful insight lies. Being open about uncertainty also changed how I communicate my work. Asking difficult questions and clearly acknowledging limitations has helped me develop a more honest and responsible approach to evidence.

Approaches to evidence synthesis, such as systematic reviews and reporting frameworks like PRISMA, have been particularly helpful in shaping this way of thinking, as they emphasise transparency, consistency, and critical appraisal across studies rather than reliance on single findings. Developing these habits early can support a more thoughtful research practice and contribute to a stronger, more reliable public health evidence base.

References

Abdous A, et al. Prevalence of Anaplasma, Ehrlichia and Rickettsia infections in dogs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Veterinary Medicine and Science. 2023.

Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/vms3.1381

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in