What's in an angle? Diet in pyrotheres and xenungulates

Published in Ecology & Evolution

One of the most fundamental questions in palaeontology is "what did this animal eat?". With this information, we can learn how fossils interacted with the world around them, and in the case of herbivores, we can paint a picture of the environment in which the animal lived. For example, if an animal ate grass, there must have been grass available in its surroundings. Fortunately, for the most part, we have an abundance of teeth available in the fossil record of mammals, with which we can attempt to answer this question. Teeth are particularly valuable for understanding palaeoenvironments because they are the only part of an animal preserved in the fossil record that has been in direct contact with the outside world.

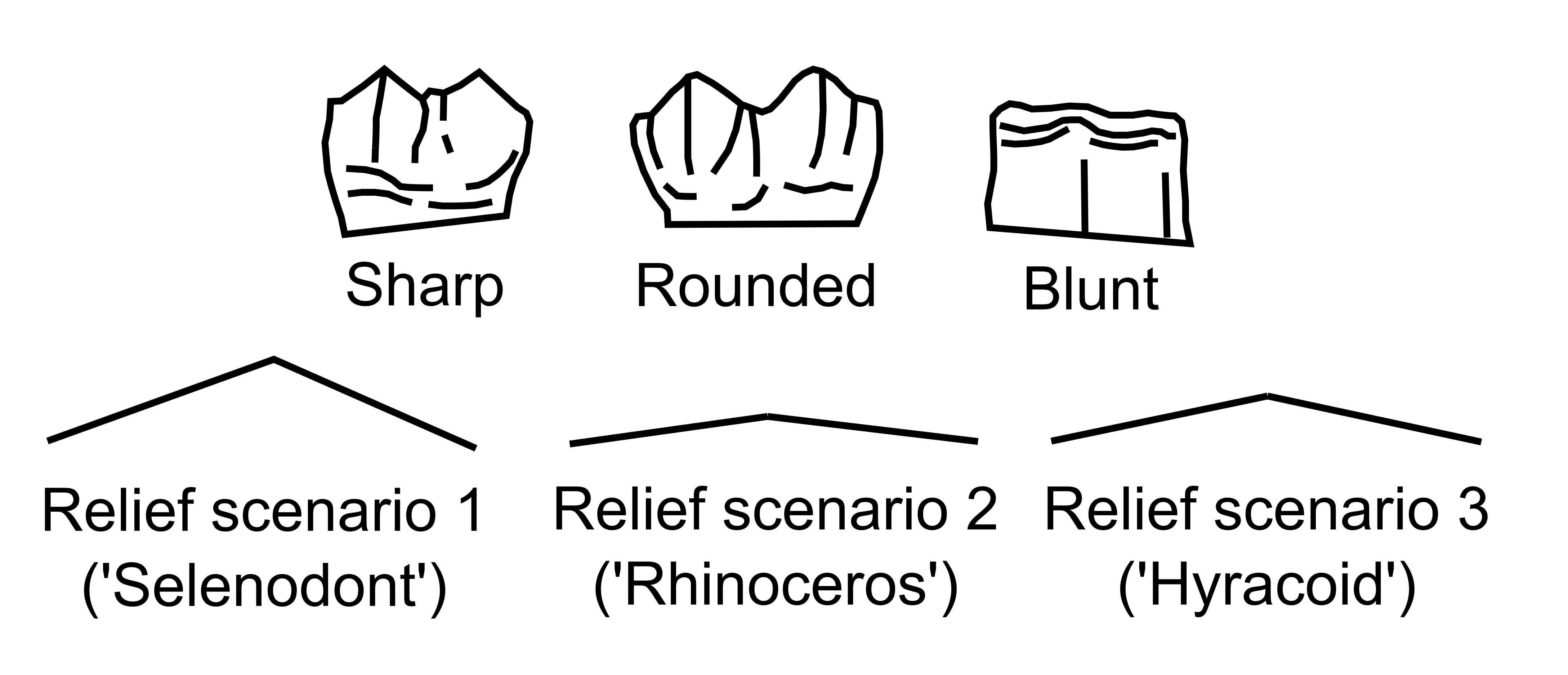

There are various ways to interpret diet from fossil teeth, all of which apply a principal of uniformitarianism (that the present is the key to the past, and vice versa). That means that we can use modern animals to try and understand fossil ones. Examples include the use of isotopes, microwear (microscopic marks on the tooth surface) or mesowear. Mesowear is a method where the shape of cusps on the teeth of herbivores are used to identify diet in relation to the balance between abrasive and attritional tooth wear. Abrasive wear tends to be driven by consumption of grasses, so this approach can broadly be used to differentiate between browsers and grazers. Mesowear has advantages over other methods because it is fast, easy, cheap and non-destructive. It also reveals diet across the lifespan of an organism, rather than in the last days of its life (as for microwear) or across evolutionary time (as for tooth crown height).

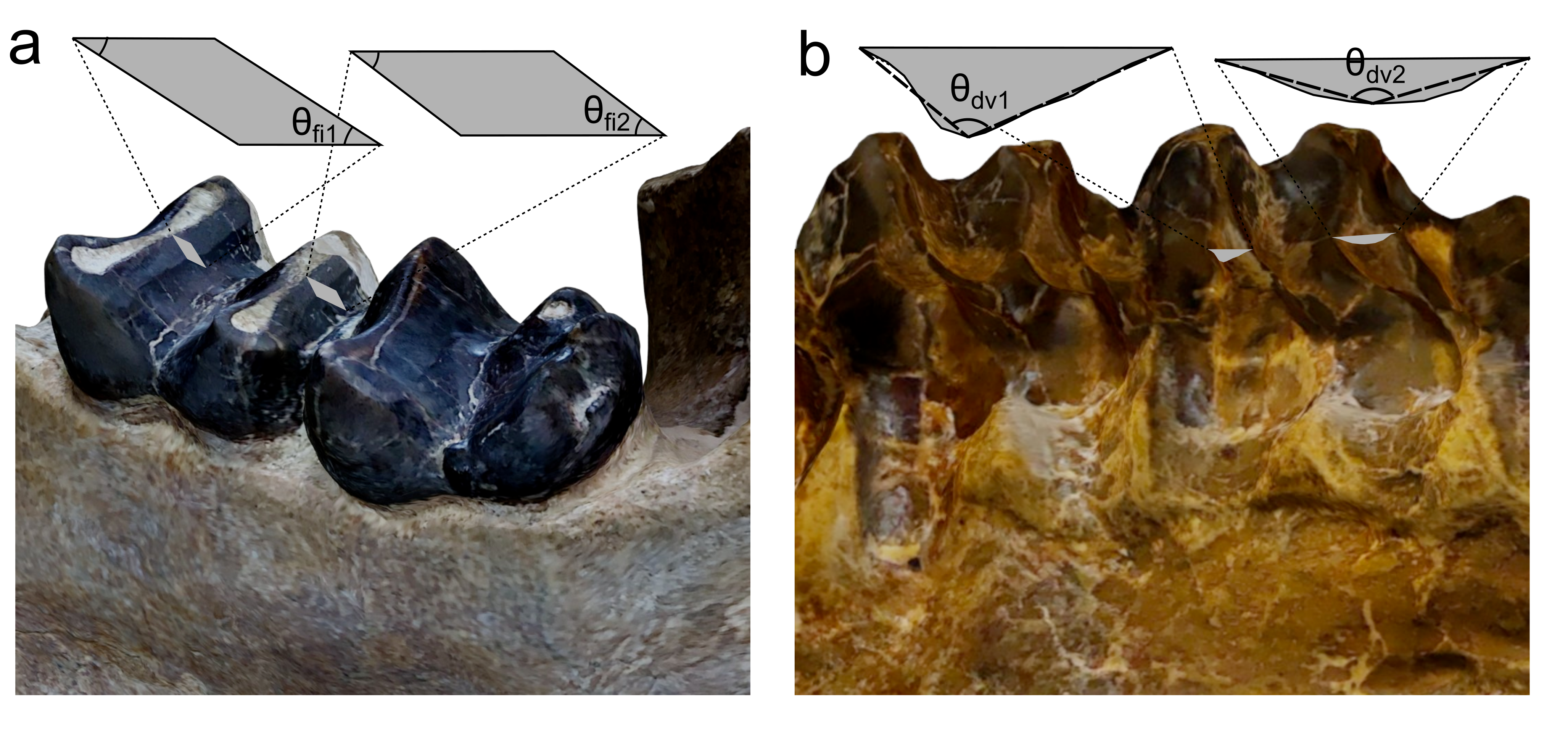

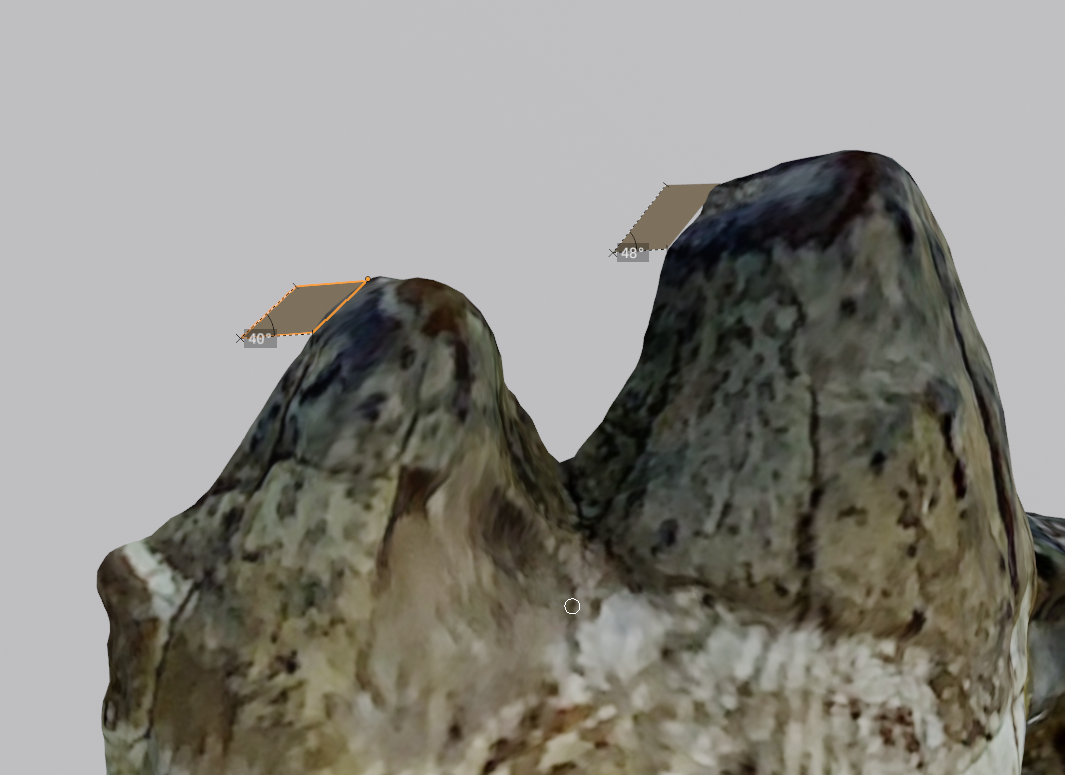

Traditional mesowear, which uses simply the shape and height of cusps, offers many advantages, but it is subjective and can be used only in a relatively restricted number of ungulate groups with a particular tooth morphology. Previous studies have found that applying traditional mesowear in tapirs for example is not useful, because the results don't match what we know about their diets. An alternative has been developed: mesowear angles. Here, specific angles can be measured in teeth, either from valleys produced when teeth are worn down, or from wear facets. This has been previously developed in proboscideans (elephants and their relatives). A new study in the Journal of Mammalian Evolution, published by a team from the University of Helsinki, Museo de La Plata and Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, used mesowear angles to identify diet in South American fossil mammals with similar tapir-like 'bilophodont' teeth: the xenungulates and pyrotheres.

The xenungulates and pyrotheres are poorly known compared to other groups of South American ungulates. Xenungulates are known from ~62 to 52 million years ago, while pyrotheres survived longer, from ~55 to 23 million years ago. Both had a range of forms, with xenungulates ranging from ~3 kg to several hundreds of kilograms, and pyrotheres including some of the largest animals in the history of South America, like the giant Pyrotherium romeroi, which weighed several tonnes. Other than some rare cases like Pyrotherium, both groups are known almost exclusively from teeth, and in some cases, only from a single specimen.

To work out what they were eating, the researchers visited natural history museums in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, France, Italy, Peru, USA and Venezuela to generate scans of the fossils using the Polycam scanning app. These scans were then used to measure the mesowear angles in Blender.

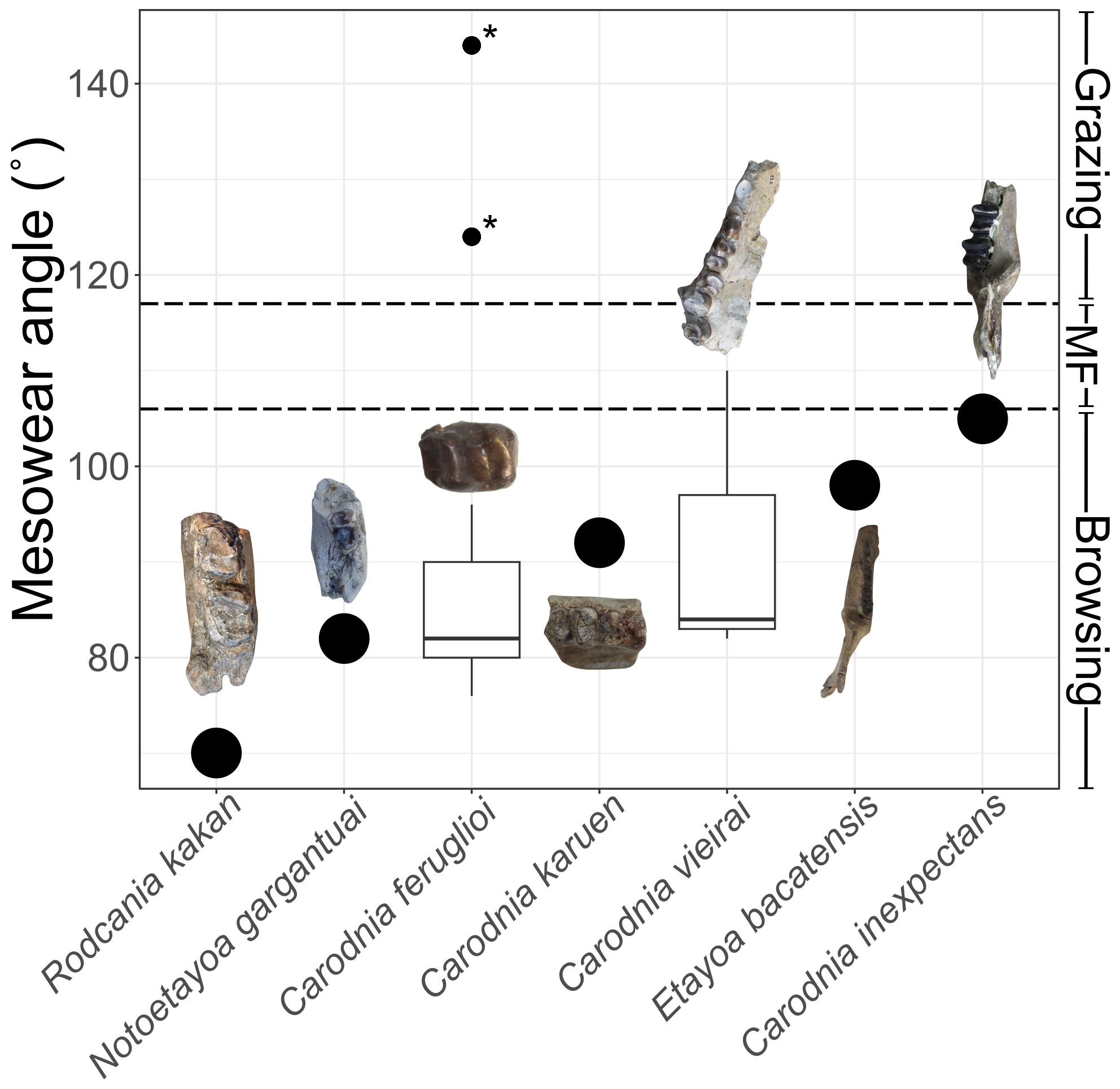

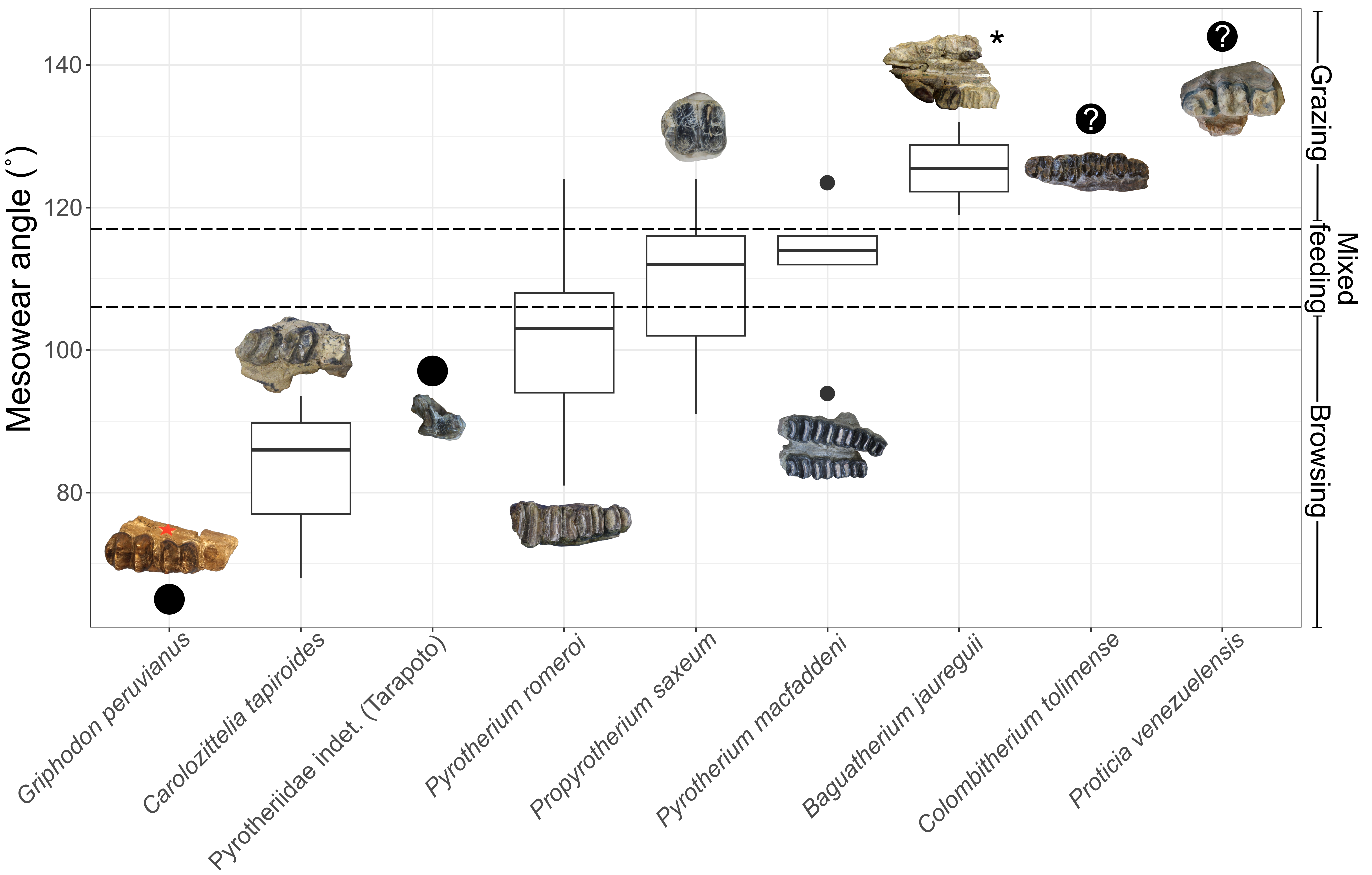

The results obtained from the pyrotheres and xenungulates were compared with modern bilophodont herbivores, for which diet was known. While this type of tooth was relatively common in the fossil record, few ungulates have such teeth today. Tapirs were included as a modern reference, in addition to marsupials, which have more varied diets. The marsupials included tree kangaroos, which were assumed to be definite browsers, as well as some other kangaroos and wallabies, which are grazers. In all cases, the mesowear angles matched the expectations from the known diets of these animals, with sharp angles indicating browsing and flat angles indicating grazing.

The authors found that the xenungulates all had sharp mesowear angles that indicate they were most likely browsers. This was independent of their size. This may reflect a diet of mostly leaves, with some fruit and/or branches.

The pyrotheres were slightly more diverse, though most species also showed these sharp angles, indicating browsing. However, two controversial species (Proticia venezuelensis and Colombitherium tolimense) had very high mesowear angles suggesting grazing. This may support ideas from other authors that these animals don't actually represent pyrotheres at all, but are instead manatees. Propyrotherium saxeum has very round, slightly shallower angles that differ from other species and it is possible this might indicate consumption of more hard fruits, while Pyrotherium macfaddeni has slightly shallower mesowear angles than the other species of Pyrotherium and this could suggest that it was consuming more grasses, possibly reflecting its environment.

Overall, the results suggest that it is possible to use mesowear angles as a relatively simple method to approximate diet, although the authors highlight the importance of taking into account factors like the age of the animals being included. In combination with other methods like microwear and isotope analysis, this allows us to better understand animals of the past, and the habitats they lived in. The mesowear angles may also provide opportunities to study other types of bilophodont herbivores in the future, given that this type of tooth is also present in many groups of primates, marsupials and fossil ungulates.

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Mammalian Evolution

Journal of Mammalian Evolution is a multidisciplinary journal dedicated to various aspects of mammalian evolutionary biology.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Ecology, Morphology, and Evolution of Whales, Dolphins, and Kin (Cetacea)

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in