A Peek Into the Nothingness

Published in Physics

During the pandemic, many of us found ourselves in confinement to our small apartments, working remotely and tracing the same few steps each day. One afternoon, an unexpected email caught my attention: IBM Q, the quantum computing program, had launched a collaboration with Brookhaven National Lab’s C2QA (Center for Quantum Advantage), inviting physicists to submit proposals to run their research ideas on cutting-edge quantum machines.

As a young high-energy nuclear and particle physicist, my first reaction was, this has nothing to do with me. But the idea lingered. I even told my wife at the dinner table about it; I said to her: how cool would it be if I can solve my physics problems on a quantum computer! A few days later, I still couldn’t shake the thought of testing some of my long-standing physics questions on a quantum computer; and I wanted to try something.

Fast forward a few years: not only did I try a few studies using quantum simulations, but I also began to see how high-energy experiments might benefit and learn from quantum information science—and how quantum technology could shine new light on the most fundamental problems in our field.

A ‘simple’ question about Alice and Bob: Imagine two spin-½ particles (usually named Alice and Bob by physicists) created together with their spins anti-aligned. If they are quantum-entangled, their spins remain correlated even if we send them to opposite ends of the universe. This is the well-known Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox, the first idea about entanglement (or more precisely, a flaw in quantum mechanics pointed out by EPR) from 1935. However, modern physics has confirmed these quantum mechanics predictions repeatedly, mostly based on the Bell-type inequalities. Experiments across the world, including at the Large Hadron Collider where the ATLAS experiment recently observed entanglement between top quarks, have validated quantum mechanics with extraordinary precision.

But I had a different question in mind. What happens if those two spin-½ particles travel through different environments and experience different interactions? How does the entanglement change?

This question is deeply relevant to our field because quarks—the building blocks of protons and neutrons—are inherently entangled inside the proton. And due to confinement (a very different kind from what we experienced during Covid, but a longstanding puzzle in modern physics;-)), quarks cannot exist alone; in a sense, confinement itself is the most dramatic example of entanglement. In high-energy collisions, we briefly separate quarks inside a proton by colliding one to another at 99.996% the speed of light. But because they cannot survive by themselves, they immediately interact with their surroundings to form stable particles known as hadrons. How this transformation happens—the exact process by which quarks become hadrons—remains one of the central mysteries of nuclear physics.

Quantum computing: an idea that led somewhere unexpected: Richard Feynman once said, “Nature isn’t classical, dammit, and if you want to make a simulation of Nature, you’d better make it quantum mechanical — and by golly it’s a wonderful problem, because it doesn’t look so easy.” He was one of the first people suggested to study quantum phenomena using a quantum computer. Therefore, one approach was to try our problem on a quantum computer. Without interactions, simulating two entangled spins is trivial—a standard exercise in quantum information courses. But modeling the full physics, including spin-dependent interactions relevant for quarks, requires circuits far beyond what current quantum hardware can execute with sufficient fidelity.

Yet this limitation turned out to be an opportunity.

It made us realize something important: high-energy experiments might be able to reveal the very quantum processes that are challenging to simulate on today’s quantum computers. Instead of viewing quantum hardware as the only tool for exploring entanglement dynamics, we could use real particle collisions—nature’s ultimate quantum computer—to guide and inspire quantum information science. This insight brought us back to experiment.

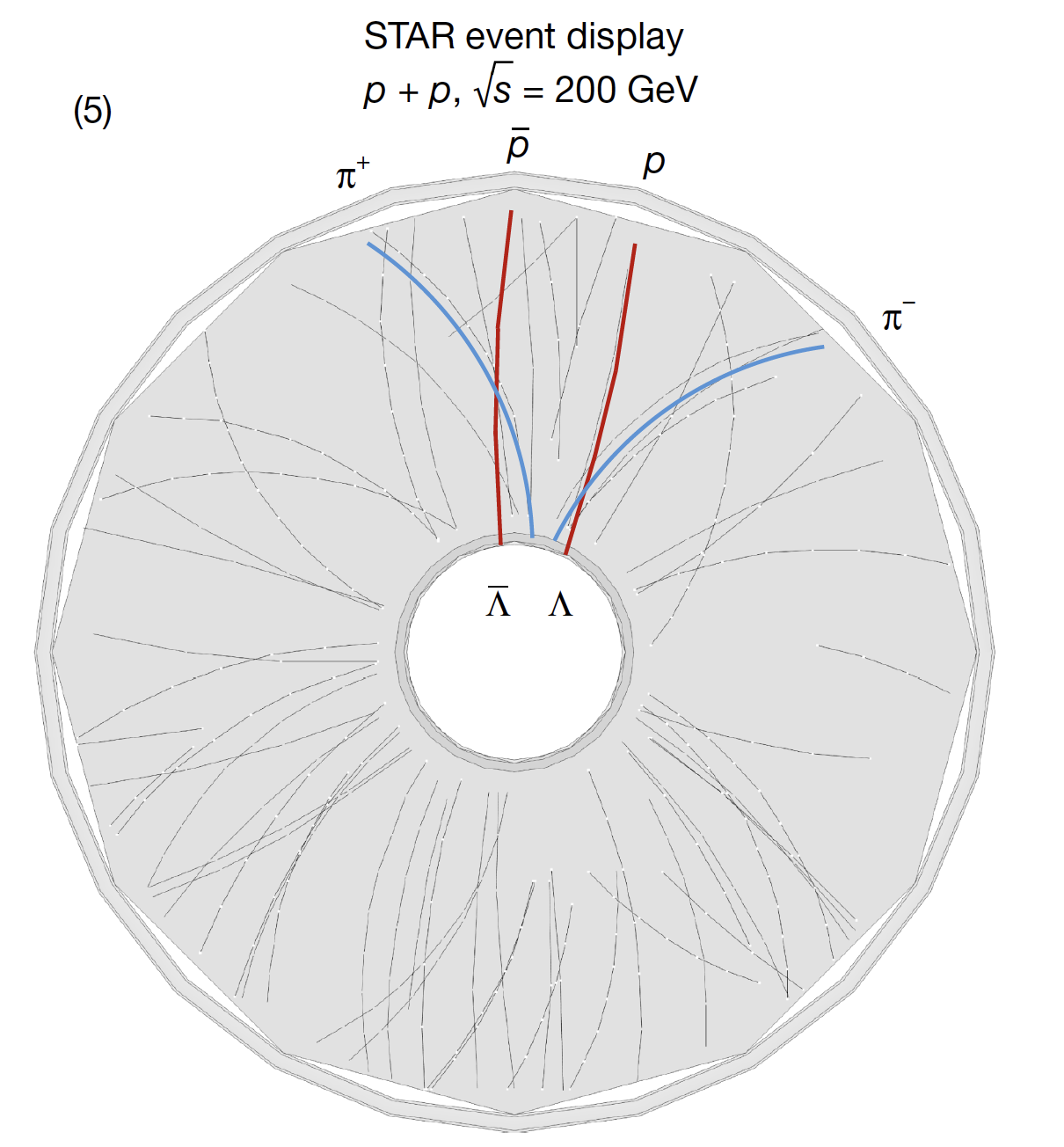

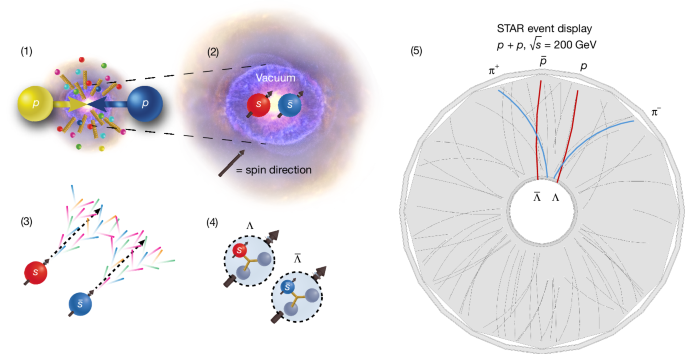

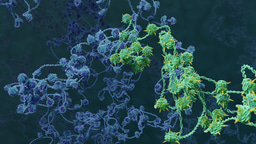

In high energy experiments, we often measure the so-called Λ hyperon for extracting information about spin, which is made of an up, a down, and a strange quark. Λ particles decay rapidly—after only 10⁻¹⁰ seconds—into a proton and a pion, and their decay pattern preserves information about their spin. Our idea is to study Λ/anti-Λ pairs and measure their spin correlations. Naively, this is like creating two qubits on a quantum computer and looking at their spins after they undergo interactions with an “environment.”. Instead, the above image is showing a real proton-proton collision event at 99.996% of the speed of light, with two Λ hyperons created and quickly decayed, which were then captured by the STAR detector - one out of the 600 millions events that were analyzed.

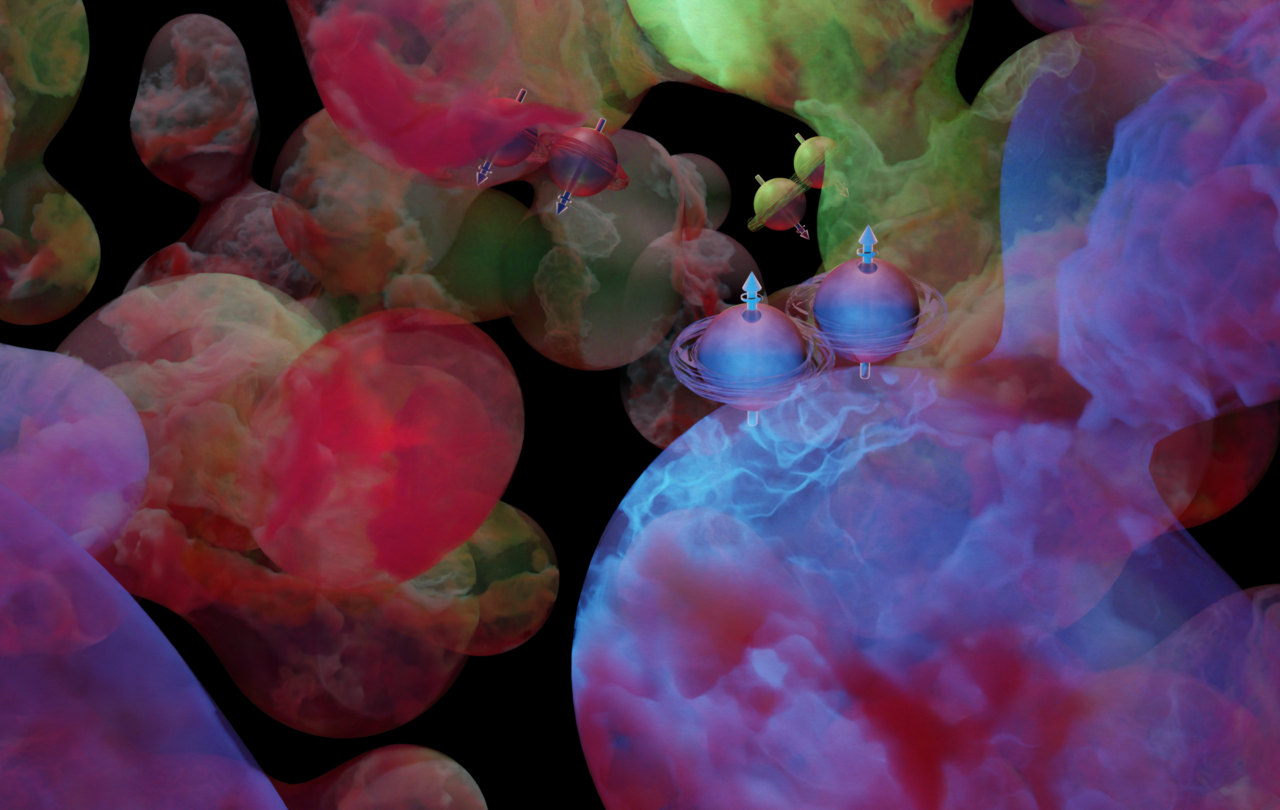

The result was very surprising. Their relative polarization—the strength of spin correlation—was nearly the maximum allowed for two spin-½ particles, suggesting the pair is in a spin-triplet state. This raised a profound question: what mechanism could produce two multi-quark particles with such extreme spin correlation? We had a few ideas when we saw it, but as it turns out - it is from the QCD vacuum. See below the GIF for an animation.

Now consider a high-energy collision. The collision injects enough energy into the vacuum to excite these virtual pairs, providing them enough energy to become real particles. And since these particles originate from the vacuum, they obey its internal rules—one of which is that quark–antiquark pairs are produced with aligned spins.

Why this matters:

-

We know the vacuum isn’t empty, and we know it produces virtual particle pairs—but we have never directly observed these pairs in experiment. This is like we found a new window that enables us to peek inside the quantum vacuum.

-

It opens a new way to study the quark-to-hadron transition, a.k.a, the confinement. A long standing problem beyond the reach of first-principle calculations or quantum simulations today. Experiment leads, providing both the challenge (and the answer) for theory to match.

-

It offers a gateway into deeper structures of the QCD vacuum—nontrivial topology, strong parity violation, chiral symmetry breaking and restoration, and more.

In short, high-energy collisions may serve as a “quantum device” capable of revealing entanglement dynamics that current quantum hardware cannot yet reach. But on a longer term, this problem could help us develop quantum simulations to advance its capability to solve new problems.

A personal note: This project began as a simple question during a quiet pandemic afternoon and grew into an experimental discovery that surprised all of us. Who would have imagined that measuring Λ–anti-Λ spin correlations could reveal the structure of the vacuum?

The day I had my first idea about measuring spin correlations of two Λs and going 'crazy' about doing a new experimental search, was my second year as a postdoc fellow at Brookhaven National Lab. It took years to secure funding (thanks to BNL’s Lab Directed Research & Development program to support young researchers as well as Department of Energy's support on STAR experiment), gather the right collaborators (both theorists and experimentalists), and dive deep into the STAR experiment’s data.

Looking back, I feel incredibly lucky . This is what I love most about being a scientist: having a crazy idea, following a question that leads to an unexpected answer, and uncovering something fundamentally important about our universe.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature

A weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology on the basis of its originality, importance, interdisciplinary interest, timeliness, accessibility, elegance and surprising conclusions.

Ask the Editor – Space Physics, Quantum Physics, Atomic, Molecular and Chemical Physics

Got a question for the editor about Space Physics, Quantum Physics, Atomic, Molecular and Chemical Physics? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in