When Congress moves from evidence to intuition

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology and Arts & Humanities

Honest people don’t lie. Or do they? Liars aren’t honest. Or are they?

One puzzling conundrum in contemporary politics is that politicians who seem to be estranged from facts and evidence are nonetheless considered honest by their followers. No one embodies this conundrum better than Donald Trump, who made more than 30,000 false or misleading claims during his first term but was nonetheless considered honest by around 75% of Republican voters.

How can a record of serial falsehoods be considered honest?

My collaborators and I have been pursuing this puzzle for several years, and we are beginning to have a good idea of what is going on. Key to understanding the phenomenon of “honest liars” is that concepts such as honesty and truth are not unidimensional. There are distinctly different ways in which honesty can be understood and how people arrive at what they consider to be the truth.

At first glance, truth and honesty should rely on evidence and consider the actual state of the world. By this criterion, Donald Trump cannot be considered honest. But there is another aspect to honesty or truth, which is less concerned with the world but focuses more on a person’s feelings, intuitions, and sincerity. So when Donald Trump claimed that the crowds at his first inauguration were the largest ever (they were not), supporters may have considered this claim to be honest if they felt that Trump sincerely believed his claim.

We have highlighted the importance of this distinction in several articles in the Nature family. In a first study led by Jana Lasser, published in Nature Human Behaviour, we examined tweets by members of the US Congress since 2011 and used mathematical techniques to ascertain how they expressed honesty. To do this we set up and validated two “dictionaries” that captured these two components of honesty, sincerity and accuracy. Words such as “feel”, “guess”, “seem” pointed to sincerity as the main attribute of honesty whereas words such as “determine”, “evidence”, “examine” pointed more towards factual accuracy.

When we related the content of tweets to the quality of news sources they linked to, we found a striking differentiation between the two concepts of honesty: the more facts and evidence were emphasized the higher the quality of news sources that was being shared. The more sincerity was foregrounded, the lower the quality of news – and the latter effect was considerably greater for Republican members of Congress than for Democrats.

In a second recent study led by Fabio Carrella, published in Nature Communications, we showed that the way in which politicians initiate a conversation on Twitter/X sets the frame for subsequent replies by members of the public – an emphasis on sincerity over evidence begets sincerity, and vice versa, factual language elicits factual replies. This “truth contagion” was observed even when the same dyads—i.e., the same politician and the same citizen—interacted on separate occasions: the citizen’s replies matched the tone set by the politician.

In our most recent study, which just appeared in Nature Human Behaviour with Segun Aroyehun as lead author, we drew a wider historical arc and examined the rhetoric in all speeches given on the floor of Congress between 1879 and 2022. We analyzed 8 million speeches to determine whether they—tacitly or explicitly—relied on an evidence-based notion of truth or an intuition-based idea. We again used dictionaries and a mathematical technique that could summarize the similarity between each speech and the dictionaries in a single number, which we called the “Evidence-minus-intuition” score (or EMI for short). A positive score implies that the speaker relied more on evidence than intuition, with a negative score indicating reliance on intuition.

To illustrate, here is a speech segment with a positive score: “Is it not true the only basis of valuation that can be established for a fixed rate of return is though the property investment account ….” And maybe you can guess the score for this one: “Oh. Yes. Your howl about the farmers of the country and the destruction of the price of wheat is nothing but the wail of the old standpatter….” These examples illustrate that it is possible to identify the tacit underlying notion of truth even when the speaker is not making specific assertions about the world—the speaker’s view of truth, specifically whether it can be ascertained by evidence or reliance on intuition and feelings, permeates their arguments at all times.

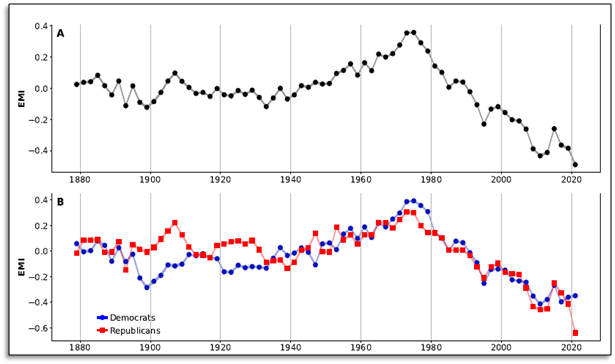

The figure below shows the temporal trend in EMI score, both overall (top) and broken down by party (bottom).

There is a striking decline of evidence-based language from the mid 1970s onward. This trend is strikingly bipartisan but during the last few years of our analysis, which coincides with Trump’s first term, the decline in evidence-based language was particularly steep for Republicans.

What does this tell us, other than that the rhetorical style in Congress has shifted?

We also examined three indicators of the welfare of the American political system and society in general: legislative productivity in Congress, polarization between the parties in Congress (which in turn is a leading indicator for societal polarization), and economic inequality in the US. For all three indicators we found that a decline in the EMI score led to worse outcomes.

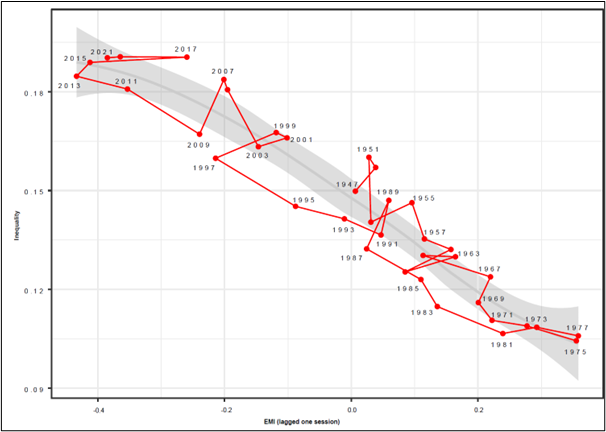

The figure below shows the association between EMI (on the horizontal axis) and income inequality (vertical). Inequality here is represented by the share of income available to the top 1%. The temporal trend is identified by labelling of the observations:

The decline in inequality since World War II until the mid 1970s, and its subsequent dramatic increase that extends to the present, is striking. It is also striking that this association was observed when the EMI was taken from the preceding congressional session (i.e., several years before the observed inequality). One interpretation of this finding is that inequality is at least partly determined by legislation, and that it takes time for that legislation to have an effect.

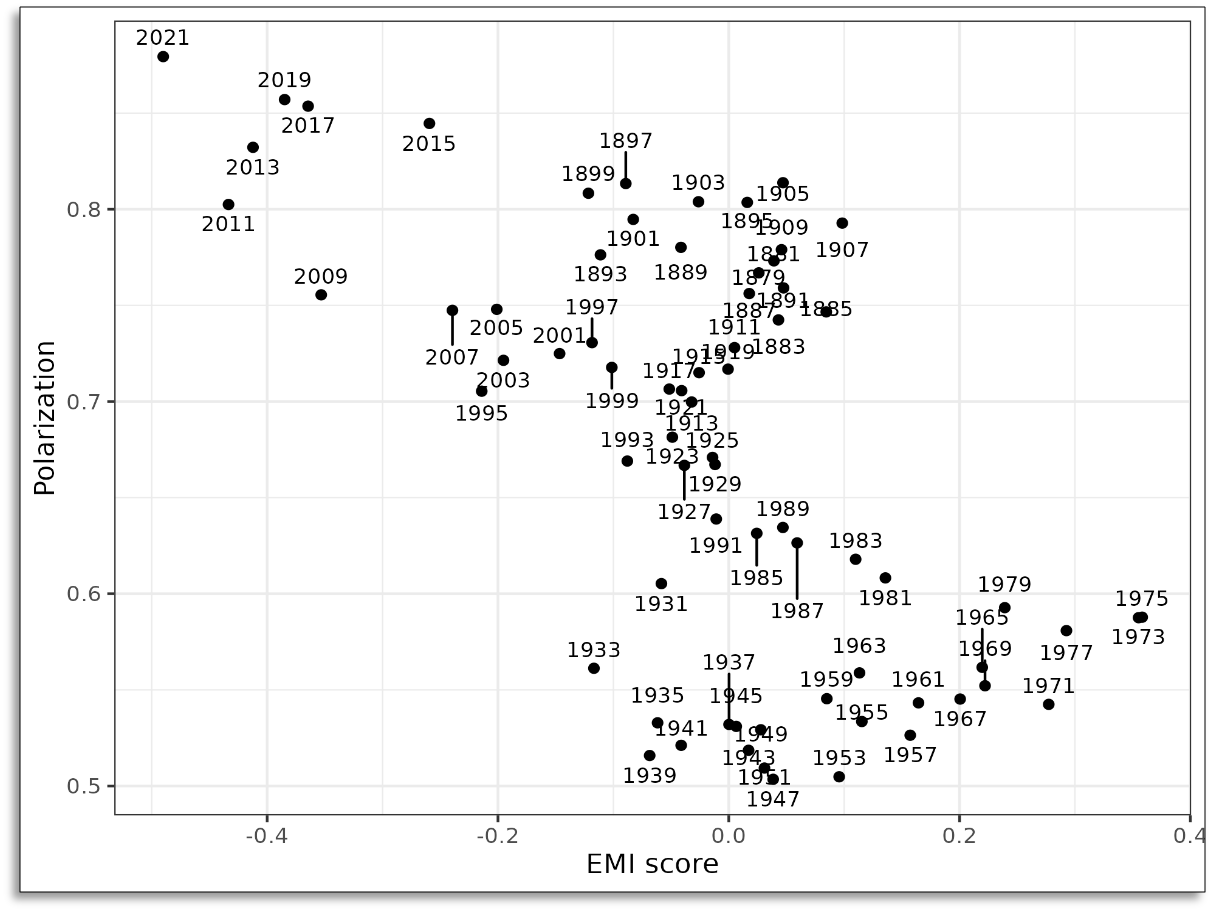

The pattern for congressional polarization is similar and is shown in the next figure:

An intriguing difference from the inequality data is that in this instance, the association involves the same session of Congress for both measures – polarization today is associated with how today’s speeches reflect the balance between evidence and intuition.

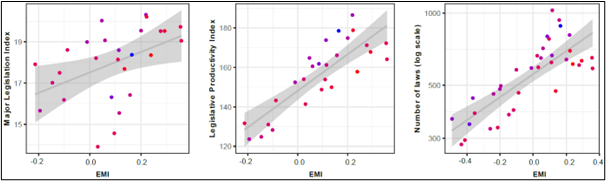

Finally, we considered three different indices of congressional output that political scientists have developed as performance indicators. As shown below, all three are positively associated with the EMI score: the more politicians tacitly or explicitly appeal to evidence in their speeches, the more productive the congressional session. Conversely, the more politicians appeal to intuition, the lesser the productivity of our elected representatives.

Words matter.

When politicians resort to intuition and “gut feeling” rather than evidence, this has flow-on consequences. It is associated with decreased legislative productivity and increased polarization, and it is also a leading indicator of societal inequality.

It is noteworthy that the trend of intuition-based language overtaking evidence-based arguments in Congress for both parties has already started in the 1970. This was way before anyone could even imagine a world with the internet in it, let alone social media and points at a deeper shift in political culture in the U.S.

However, there are also two hopeful messages to be found in our research: First, as shown in our analysis of utterances on Twitter, Democrats use sincerety-based language without resorting to the sharing of untrustworthy sources. Second, the recent de-coupling between the language used by Democrats vs. Republicans in Congress shows that a change in culture is possible.

Words matter, but we have power over the words we choose.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in