When Missing Data Can Change the Story

Published in Astronomy, Earth & Environment, and Research Data

Long-term change in Earth’s upper atmosphere is one of those scientific topics where patience is not just a virtue, but also a requirement. To detect trends related to space climate and long-term anthropogenic forcing, researchers often rely on observations that span decades, sometimes more than half a century. These long records are invaluable. They are also, almost inevitably, imperfect.

This paper was born from a simple question that kept coming back during our own work on ionospheric trends: how much do data gaps really matter?

In ionospheric research, and in many other areas of geophysics, missing data are often treated as an inconvenience rather than a central methodological issue. We know they exist. We work around them. But we rarely quantify how much they can bias the results like annual mean values and long-term trends.

Why data gaps are unavoidable:

The ionosphere has been monitored routinely since the mid-20th century, and some decades before, using ionosondes (ground-based instruments that probe the upper atmosphere using radio waves). Some stations, such as Juliusruh in Germany, provide remarkably long and consistent records dating back to the 1950s. However, even these “gold standard” datasets can contain gaps.

Instruments fail. Power goes out. Maintenance is delayed. Environmental conditions interfere with measurements. Some data are discarded after a quality control. Over decades, these interruptions add up.

For climate-scale studies, researchers usually work with annual mean values, computed from monthly means of monthly medians archived by international data centers. A common rule of thumb in the community is to compute an annual mean only if at least 8 months of data are available. This criterion is widely used.

Our study set out to test whether this rule really holds up.

Turning the problem around:

Instead of starting with incomplete data and trying to “fix” them using reconstruction or machine-learning techniques, we took a different approach. We started with the most complete foF2 time series available (the critical frequency of the ionospheric F2 layer, a key parameter for radio communication and space climate studies) and then deliberately we generated gaps.

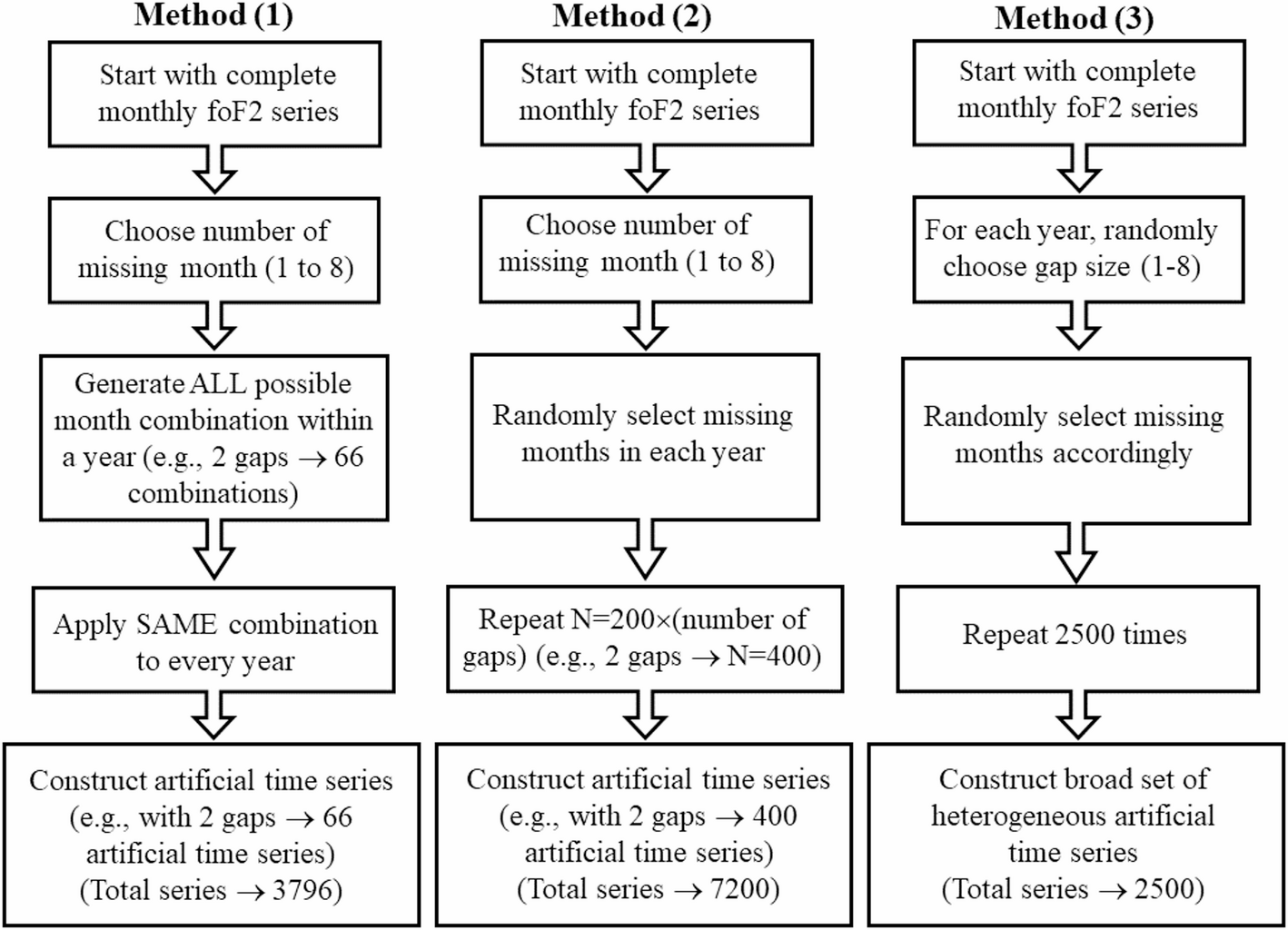

Using long records from four well-established ionospheric stations, we generated thousands of artificial datasets in which we introduced missing months in controlled ways:

- fixed missing months repeated every year,

- randomly selected missing months each year,

- and fully random scenarios where both the number and position of gaps varied.

By comparing the results from these incomplete series with those obtained from the original complete data, we could directly measure how missing data affect annual means and long-term trends.

What we found:

One of the most striking results is that the effect of missing data is not linear. Losing one or two months per year generally has a modest impact. But once the number of missing months reaches six or more, errors increase sharply.

For annual mean values, deviations can reach 20–30%, large enough to exceed the natural year-to-year variability of the ionosphere itself. In practical terms, this means that a biased annual mean could misrepresent the actual state of the ionosphere more than real physical variability does.

The consequences are even more serious for long-term trends, which are small signals extracted from noisy data over decades. In some cases, missing data can reduce an estimated trend to nearly zero, or even change its sign, effectively masking the atmospheric response to greenhouse gas increases.

At the same time, we found something reassuring: when all possible combinations of missing data are considered, positive and negative deviations tend to compensate. The problem is not systematic bias in one direction, but increased uncertainty. And uncertainty matters enormously when interpreting long-term climate signals.

Why this matters beyond ionospheric physics:

Although this study focuses on one ionospheric parameter, the implications are much broader. Many areas of space and atmospheric science rely on long-term observational datasets that are incomplete by nature. Trend detection in such records is always challenging, and missing data silently add another layer of uncertainty.

Our results provide quantitative support for a practice that many researchers already follow: requiring at least eight valid months per year to compute reliable annual means. This threshold is not arbitrary; it is grounded in statistics.

More importantly, the study highlights the need to explicitly account for data completeness when interpreting long-term trends, rather than treating it as a minor technical detail.

Looking ahead:

This work opens the door to several follow-up questions. How do missing daily values affect monthly medians? What happens when trends are estimated seasonally rather than annually? And how do different gap-filling or reconstruction techniques compare to simply working with incomplete data?

Space climate research depends on long memories, both human and instrumental. Understanding the limits of our data is essential if we want to confidently separate natural variability and non-natural long-term change.

Sometimes, the most important signal is not what the data show, but what they are missing.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Space

Previously Earth, Moon, and Planets. Discover Space is an open access journal publishing research from all fields relevant to space science.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Astrophysics of Compact Objects: Connecting Theory with Observations

Astrophysics of compact objects—such as black holes, neutron stars, and white dwarfs—stands at the intersection of extreme physics (from the strongest gravitational attraction to the outflow of matter at speeds close to the speed of light) and state-of-the-art observations. These dense remnants push matter, energy, and spacetime to their limits, providing natural laboratories for testing theories of gravity, nuclear physics, and high-energy processes. Advances in multiwavelength astronomy and gravitational wave detection now allow us to probe their structure, dynamics, and environments with unprecedented detail. By linking theoretical models with observational signatures - whether in UV/X-ray/Gamma spectra (using data from space missions like NuSTAR, XMM-Newton, Chandra, IXPE, ExpoSat), polarisation (IXPE), and pulsar timing (NICER and AstroSat), or gravitational waveforms (LIGO, Virgo)- we can unravel the fundamental laws governing the most extreme corners of our Universe.

Topics of interest include, but are not limited to:

- Gravitational wave astrophysics of compact object mergers

- Equation of state for dense nuclear matter

- High-energy emissions from neutron stars and black holes

- Observational signatures of exotic compact objects

- Theoretical modeling of accretion processes

Keywords: Compact objects, black hole, neutron star, white dwarf, accretion, gravity, Ultraviolet-, X-ray spectroscopy, timing

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Tensions in the Standard Model of Cosmology

This topical collection seeks to bring together cutting-edge research on the growing set of observational tensions that challenge the standard ΛCDM model of cosmology. These include both long-standing problems and emerging anomalies across multiple cosmological probes and key parameters, such as the Hubble tension, weak lensing measurements of the S8 parameter, hints of a dynamical dark energy sector, and inconsistencies between cosmological constraints on the total neutrino mass and results from oscillation experiments.

We welcome contributions that engage with the following questions:

• What is the physical origin of these tensions, and do they point to a breakdown of the standard cosmological framework?

• How can we develop and test well-motivated extensions to ΛCDM that address multiple anomalies in a consistent and predictive manner?

• To what extent do observational and theoretical systematics impact our interpretation of current data, and how can we critically reassess their robustness?

We are particularly interested in works at the intersection of cosmology, astrophysics, and fundamental physics that identify key obstacles through multidisciplinary approaches spanning theoretical model building, data analysis, and methodological innovation. As the volume and precision of cosmological data continue to grow with missions such as Euclid, JWST, DESI, LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA, and the Simons Observatory, achieving a clear understanding of the standard model of cosmology (and any viable extensions) has become an increasingly urgent scientific goal.

List of Topics covered:

• Cosmic distance ladder,

• Supernova cosmology

• Hubble tension — Early and Late time solutions;

• Hubble tension — Systemtics

• Measurements of the S8 parameter

• Hints for dynamical dark energy

• Neutrino Cosmology

• Cosmic Tensions and dark matter, dark energy, and inflation models

• Numerical methods for cosmology

Keywords: Cosmology, Cosmic Tensions, Hubble tension, Measurements of S8, Large-Scale Structure, Neutrinos, Dynamical Dark Energy

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 01, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in