Why don't you remember what you already know?

Published in Neuroscience and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

In this post, , we explore how anxiety—that feeling of nervousness or worry about what might happen—interferes with the way you remember things. We’ll also see whether the way information is presented (in words or through your senses) makes a difference. To understand this, we’ll draw on recent research that offers fascinating clues about how your mind works (or better said, your brain!).

Concepts in your brain?

Imagine that every idea or thing you know (“apple,” “friendship,” “physics”) is like a super-fast web of connections in your brain. We will call these networks dynamic concepts (Muñoz-López & Hernández-Pozo, 2025).

These concepts constantly change with what you learn and feel! The key to understanding how they are formed, transformed, and used lies in how your brain stores memories.

Memories as traces of activity

Your brain stores memories as complex traces left by your experiences—these are called engrams. But they’re not like footprints in the sand; rather, they are networks of brain cells (neurons) working together across different areas of your brain.

Each time you experience something—seeing an image, hearing a sound, smelling something, or touching a surface—specific groups of cells are activated and connected because they fired together. It’s like how people who enjoy the same kind of music gather together—they’re linked by the same stimulus (the same song).

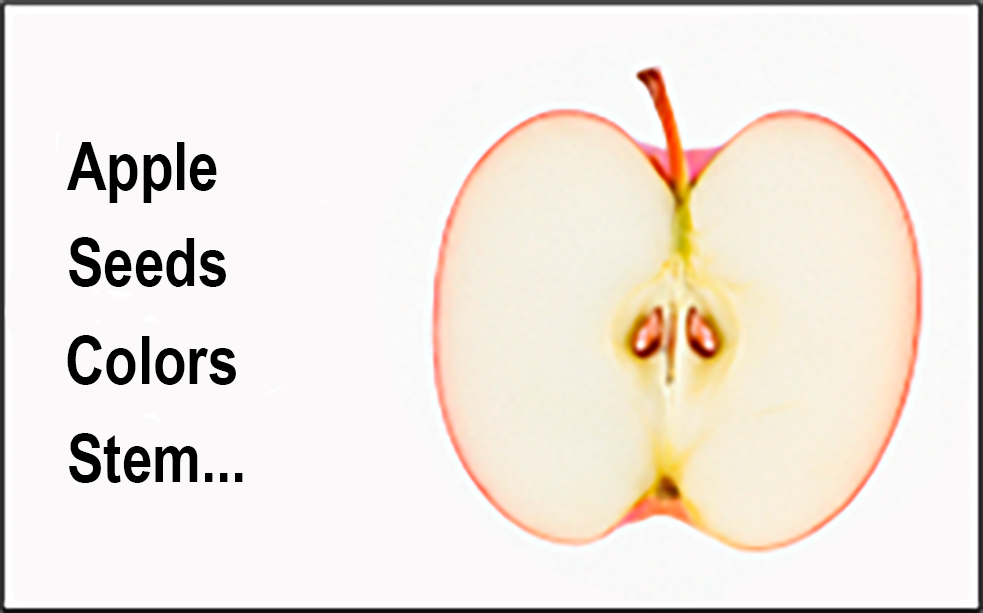

These cellular connections form the engram of that memory or concept. What matters is that these sets of neurons store the different features of what you initially perceived. For example, the engram of an apple may link the neurons that registered its red color, round shape, sweet smell, and the feeling of biting it. However, that engram can later change—if you frequently encounter green apples, that color will also become part of the same engram.

How do we remember, then? According to Engram Theory, recall occurs when something reactivates some of the neurons that were activated together before. For example, if you are talking about fruits that grow on trees and see the color red, this visual cue activates the neurons associated with that color, which in turn reactivates the previously stored information—sweet smell, round shape, pleasant taste—leading you to recall “apple.”

Words or reality? The brain decides

A study by Muñoz-López & Hernández-Pozo (2025) analyzed whether we learn equally well when information is presented through words or through sensory experience (images, sounds, smells, touch, etc.). Think of learning about a new animal: is it easier to read a description or to watch a video, hear its sound, and maybe even touch its fur? It turns out that your brain processes verbal and sensory information differently. Words activate the language areas, while sensory input activates areas related to sight, hearing, smell, touch, and so on.

Anxiety: the silent enemy of learning

Here’s where anxiety comes into play. Scientists have observed that this state—whether daily anxiety or the kind that appears under pressure, like before an exam—can influence memory.

That is, anxiety interferes with the reactivation of the neuronal groups that form memories (the engrams), making it harder to retrieve information when needed.

Why does this happen? Beck and Haigh (2014) point out that we process information in two ways:

- Automatic processing: fast and unconscious, used in alert or survival situations. It consumes few resources but works with general categories and can make mistakes.

- Reflective processing: slower and conscious, requiring more effort but allowing for more precise interpretations.

The problem is that anxiety tends to trigger the automatic route, as it appears when we feel in danger of what might happen. Therefore, during stressful events, recalling words, concepts, or data (reflective processing) becomes more difficult.

In contrast, nonverbal memories—like images or sensations—tend to surface more easily, though less accurately.

Can Sensory Learning Overcome Anxiety?

Interestingly, anxiety may affect learning less when information reaches you directly through your senses, rather than being mediated by words. Why? Perhaps sensory information is processed more immediately and is more physically grounded, making it more resistant to the “noise” that anxiety produces in the brain. Learning through images, sounds, smells, and textures could therefore create a stronger connection to information—even under pressure.

Common memory errors

Have you ever had a word “on the tip of your tongue”? That’s a memory error!

It occurs when the engrams containing sensory information are reactivated but not the ones containing textual (semantic) information, which depend on higher brain functions.

The research also examined other errors—like when you accidentally call your partner by a friend’s name, or call your teacher “mom.” This type of mistake is called a “slip of the tongue”. It happens when a sensory stimulus reactivates a neuronal engram that usually activates with a specific name (for example, your ex’s). When a similar stimulus occurs, that name—stored in that engram—is mistakenly expressed.

Anxiety can increase the frequency of these errors (Muñoz-López & Hernández-Pozo, 2025B), especially when recalling verbal information. Other nonverbal errors were also identified, such as:

- Feeling of Knowing (FoK): when you know you want something sweet but don’t know exactly what.

- Bias of Perception (BoP): when you perceive something through your senses and react as if it were something else—for example, being told to grab a fruit of a shown color (green), but mistakenly picking an orange.

Both FoK and BoP occur in nonverbal situations and are amplified by anxiety (Muñoz-López & Hernández-Pozo, 2024B).

These Errors Aren’t Random. they have specific causes and appear systematically. Understanding these processes can help us improve memory and reduce the frustration that comes with such common mistakes.

Conclusion: Know your brain

In summary, anxiety is an important factor that affects memory, and the way information is presented (in words or through your senses) makes a real difference.

Understanding how your brain works under pressure can help you find better ways to study and learn.

There’s still much to discover, but these findings offer valuable insights into how to optimize learning. The most powerful lesson is that the brain is not a rigid machine—concepts, memories, and engrams change with experience and emotional context. This means we can train and enrich memory strategically. For instance, alternating between textual and sensory study, or recreating exam conditions while practicing, can strengthen engrams, making them more resistant to anxiety—or even linking them to it positively.

Did you know some boxers train in the same ring where they’ll fight, imagining the audience beforehand, so they won’t be emotionally affected during the real match?

Also, recognizing that recall errors—like slips of the tongue or the “tip-of-the-tongue” phenomenon—are not personal failures (or an inability to forget someone) but a natural part of memory function, helps us face moments of forgetfulness with greater patience and confidence.

Finally, knowing how your brain works not only helps you pass exams but also gives you strategies to learn better, communicate more precisely, and, most importantly, realize that you are in constant transformation. And perhaps the most inspiring part: by understanding your brain, you also learn to know yourself better.

Keywords: engrams; memory; anxiety; tip of the tongue; retrieval.

References

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in