Why fossil ribs are a researcher’s nightmare — and how 3D printing saves the day!

Published in Social Sciences and Ecology & Evolution

In 2020, I was just an innocent MSc student when Markus, who would later become my PhD supervisor, suggested I focus my research on hominin comparative rib anatomy. It felt like an incredible opportunity, and I obviously said yes since I really wanted to learn more about human evolution and dive into the latest analytical methods. It was all smiles and optimism until I actually started working with the ribs, and then… the drama began. What seemed like a simple anatomical structure quickly revealed itself to be a complex, chaotic, and often frustrating puzzle, especially when working with fragmentary archaeological material. I consider this is a part of paleoanthropological research that often remains hidden from the public eye, but it’s time to pull back the curtain.

First, although ribs are very informative about body shape, posture and breathing kinematics, they are scarce in the hominin fossil record. Very scarce. This makes their study particularly challenging due to the simple fact that we often lack enough material to work with. In the best-case scenario, at least one rib per costal level is preserved in decent conditions, which allows for reliable thoracic reconstructions. Unfortunately, in general terms, many costal levels are completely missing, and the ones that are present are severely damaged, fragmented, and comingled. That means you have to figure out which rib any tiny fragment belongs to… and from which side of the body it is!

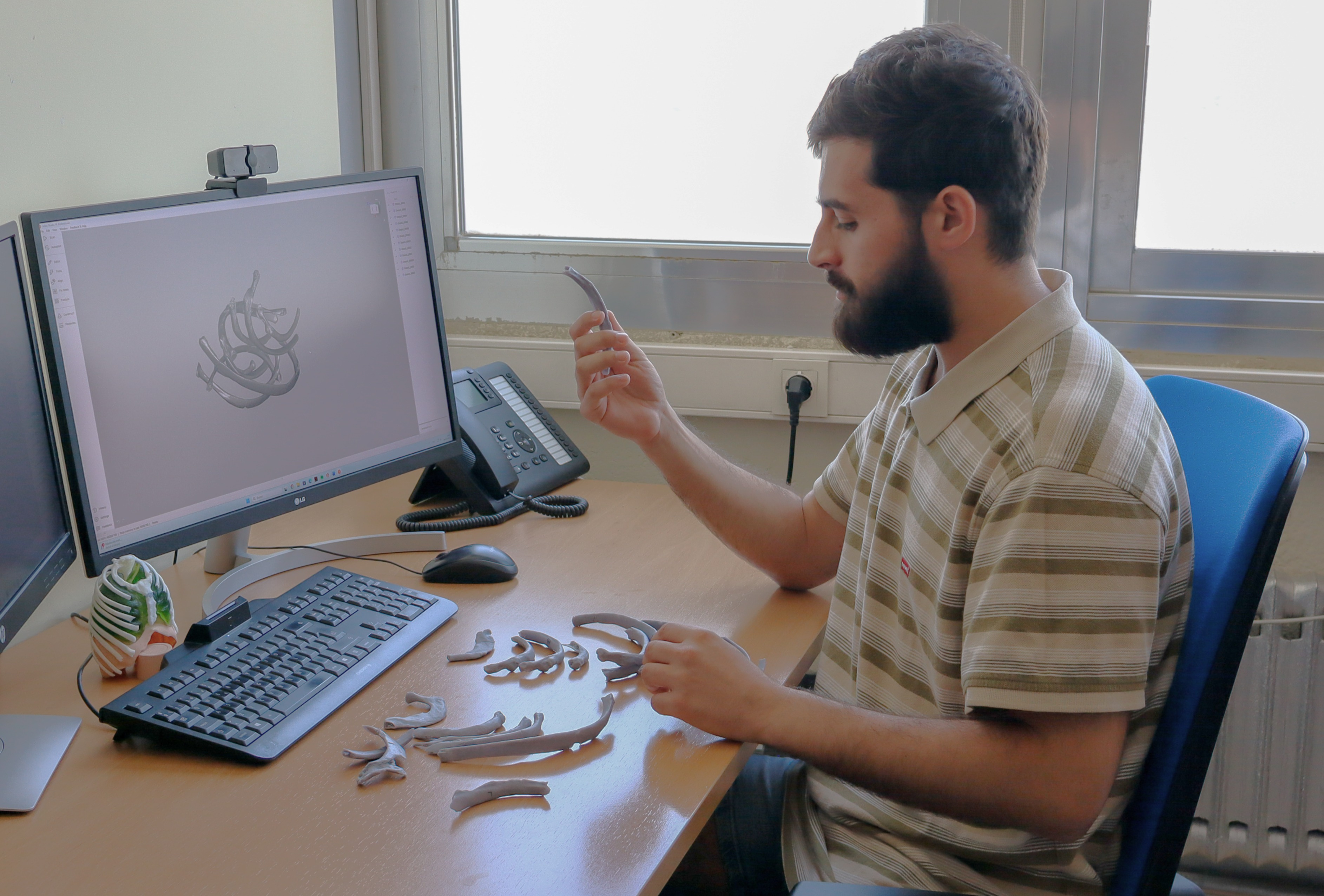

Just when you think things couldn’t get more complicated, there is another factor to be considered: the difficulties of doing all of this on your computer. However, it is not all bad news. One of the great advantages of digital paleoanthropology is that data from the other side of the planet can land in your inbox in seconds. Even better, many fossil scans are publicly available, helping to democratize paleoanthropological research like never before. But there is a trade-off. When everything happens on a screen, it is easy to lose sight of the real scale of what you are looking at. No matter how detailed the 3D model is, a virtual bone loses the tangible feeling of a real thing —its size, weight, and physical relationship to the rest of the skeleton become abstract, almost theoretical. Here is where 3D printing come to the rescue!

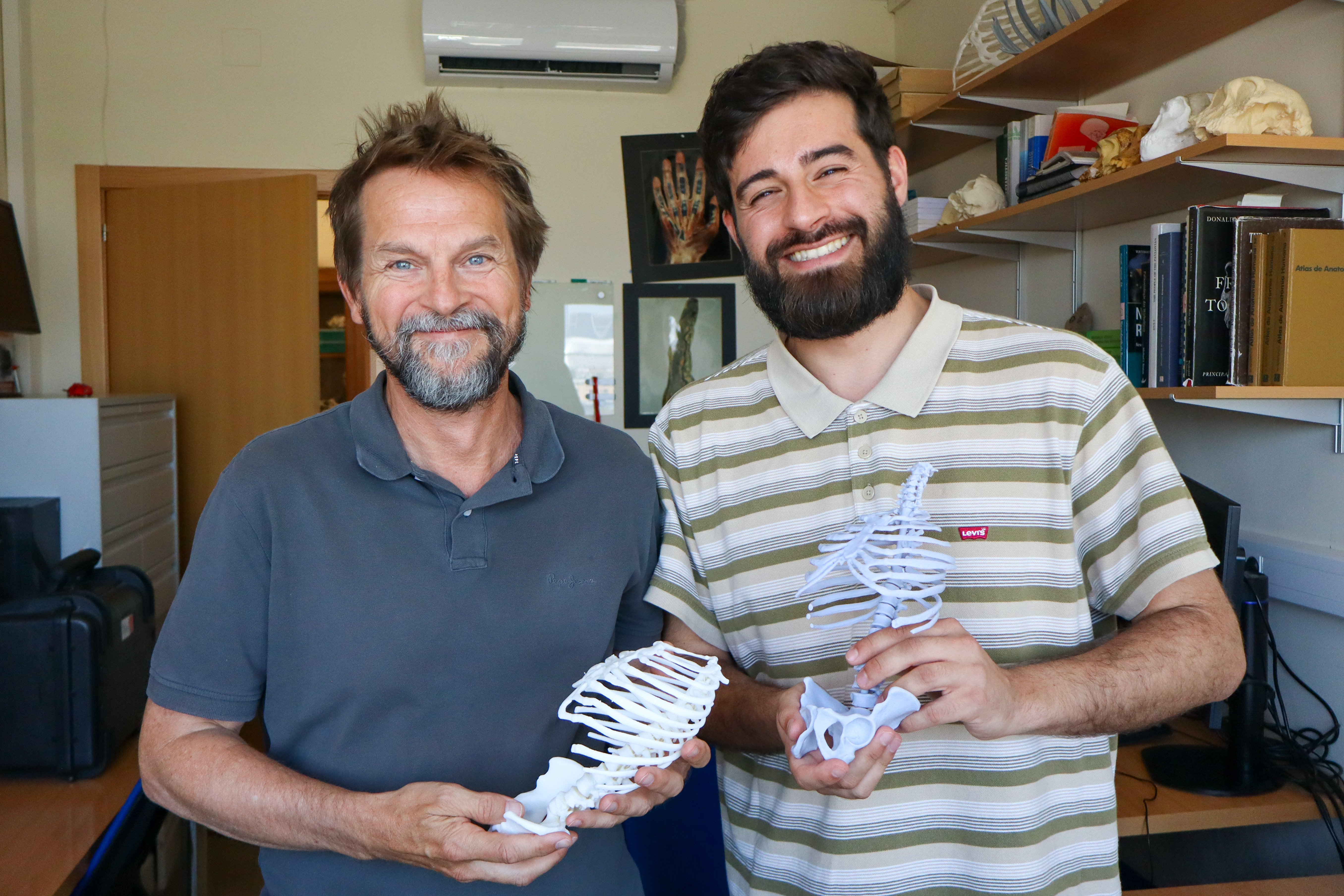

As soon as I started reconstructing the fossil H. sapiens ribcages for our recent publication in Communications Biology, I realized that trying to sort ribs on a screen was frustrating. Honestly, I couldn’t make sense of anything. The fragments were all mixed up, size differences were hard to interpret, and therefore classification was nearly impossible. It was during one of those slightly desperate brainstorming sessions with Markus and the team that we decided to try printing the fragments — and suddenly, things started to fall into place. Once the ribs were properly sorted, the digital reconstruction moved on and the workflow continued all the way to obtaining our interesting results on human ribcage evolution. We even used the facilities of the Virtual Morphology Lab (MNCN-CSIC) to 3D print out what is probably the first reconstructed torso belonging to a late Pleistocene H. sapiens!!

Regarding our research, the results suggest that there is significant morphological variability in both fossil and recent H. sapiens that goes beyond the generalized gracile body plan traditionally proposed for our species. This variation might depend not only on genetics but also on climatic plasticity. While slender ribcages seem to be unique to H. sapiens, stockier ones — geometrically similar to those found in other Homo such as Neanderthals— are also part of the morphological variability within H. sapiens. Consequently, we conclude that discrete features are crucial for distinguishing hominins in ribcage studies.

Now that we’ve lived to tell the tale… what’s the take-home message of our story? That researcher’s relationship with ribs is complicated, that digital tools are amazing but have their limitations, and that sometimes the best solution is to hit “print” and get your hands on some plastic bones. Reconstructing ancient ribcages might not be easy, but with a bit of patience, a good 3D printer, a strong cup of matcha, and the support of an experienced research team, it’s totally doable!!

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in