World AIDS Day 2024 - A brief history

Published in Social Sciences, Microbiology, and Sustainability

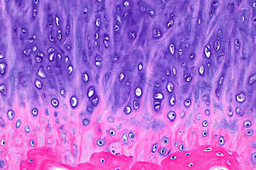

Since the 1980s, communities across the world have felt the effects of the AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) epidemic, losing loved ones and facing social isolation whilst battling Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Over 35 million people have died of HIV or AIDS related illnesses in the past 40 years, and it is estimated that a further 38 million people are living with it right now. HIV is a retrovirus that attacks the body’s immune system by targeting white blood cells, rendering the host vulnerable to infectious disease. It is spread through the sharing of body fluids and can also be shared from mother to baby. At its most advanced stage, HIV leads to the condition known as AIDS.

Springer Nature publishes a range of HIV-related research, including medical interventions, epidemiological studies and the impact of healthcare service delivery on AIDS patients. Publications relate to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), aiming to connect researchers and policymakers with relevant studies that can help us achieve targets 3.3 and 3.7, which cover ending the AIDS epidemic and ensuring universal access to sexual health services.

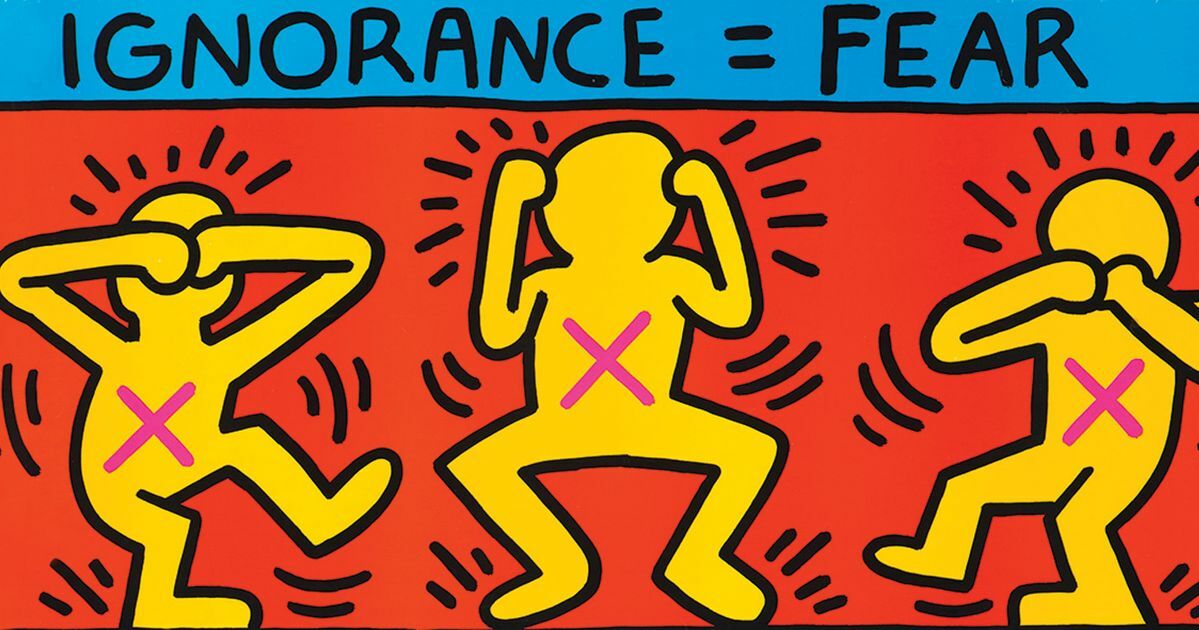

In 1981, the U.S. Center for Disease Control published a case report depicting a rare lung condition, with five previously healthy gay men being treated for this issue. Unbeknownst to immunologists at the time, this was the first official recording of what we now know as the AIDS epidemic. HIV began to spread across communities, with panic and fear growing amongst society, propagated by the lack of knowledge surrounding the virus. Alongside this fear, homophobia became rampant, with gay man being actively refused health services despite initially suffering the most. The initial lack of information surrounding what HIV truly is, alongside how it is caught and spread, resulted in quarantining and extreme caution around those who had tested positive, including the prevention of a child from attending school. Amid this widespread panic, activists involved with the gay rights movement started campaigning for HIV/AIDS to be recognised as a human rights issue, emphasising that infected people faced additional risks due to the intense discrimination that was taking place. This movement received the support of public health officials, due to concerns that the growing stigma may prevent people from seeking testing or accessing healthcare. In the wake of this movement, it has been argued that specifically protecting vulnerable social groups can empower them to seek education, opportunities and protection from violence.

The development of HIV treatment is extremely efficient: the first HIV test was approved in 1985, and that same year clinical trials of antiretrovirals also began. Antiretrovirals were continually developed and improved, leading to the breakthrough success of Highly Active Antiretroviral Treatment (HAART), which combined three different ARVs and significantly reduced AIDS-related deaths. However, low- and middle-income countries are still extremely vulnerable to HIV due to the prohibitive cost of this treatment, particularly those in resource-poor settings. Individual country studies have suggested that the risk factors prevalent in some countries mean that access to HAART does not have a huge impact on HIV-related mortality rate, indicating there is still a significant amount of work to be done. Current HIV research focuses on long-lasting, accessible treatments, such as vaccine availability, preventative medicine, and promoting access to testing and education.

The immense progress in ending the HIV epidemic is largely a result of the development of two key drugs: PrEP and PEP. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a drug that can be taken by somebody HIV-negative, prior to exposure to HIV via sexual activity. PrEP has had a huge impact on many communities, not only in reducing the spread of HIV but by providing an opportunity for a HIV-positive individual to have safe sex. The availability of PReP has delivered a sense of hope by allowing HIV-positive people to ‘have relationships and build bridges’ once more. Additionally, exposure to HIV is no longer the permanent change of the past, as the development of Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) has allowed. PEP is a combination of drugs, which if taken promptly can prevent the HIV virus from taking hold of the body. However, it should be noted that PEP is not always effective and should be used as a ‘last resort’ rather than being fully relied on for protection.

The AIDS epidemic is unique in the sense that its long-lasting effects are still felt somewhat disproportionately by a singular demographic: the LGBTQ+ community. AIDS bereavement can become complicated for many, as despite the fact a HIV-related death is often anticipated, the young age at which the victim passed away presents a particular sense of tragedy. This trauma is also felt by medical professionals in the AIDS field, who experience high levels of pain and stress as a result of exposure to these tragedies daily. The increased amount of stigma associated with HIV in comparison to other widespread diseases also made many feel isolated in their loss, compounded by the need to grieve for multiple members of their community at once. In any case, losing a partner or friend causes unimaginable grief, however when accompanied by the loss of friends and a support network this becomes even more challenging to deal with. The AIDS epidemic was the first time Multiple Loss Syndrome was widespread in a non-violent setting. For many, grieving a partner occurred within a damaged social network and a ‘devastated community’. Multiple Loss can also be used to describe the various senses of loss faced by this population in a broader sense: the loss of safety, support and community felt by many. However, the AIDS crisis gave many the strength to continue fighting for engagement across boundaries, empowering activists to fight for change to prevent future crises from disproportionately damaging certain networks.

Although there is currently no cure for HIV, immediate priorities focus on increasing access to prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care. To meet the SDG target 3.3 of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030, WHO, the Global Fund and UNAIDS have all developed global strategies to ensure that progress is made, and that this can be achieved. Short-term aims include ensuring 95% of all people living with HIV have a diagnosis and can access retroviral treatment options by 2025. By promoting Springer Nature content on World AIDS day, we hope to emphasise the huge progress made in tackling the HIV virus, and connect research with researchers and policymakers to help the fight against AIDS.

Picture source: Keith Haring

https://hero-magazine.com/article/175640/keith-haring

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in