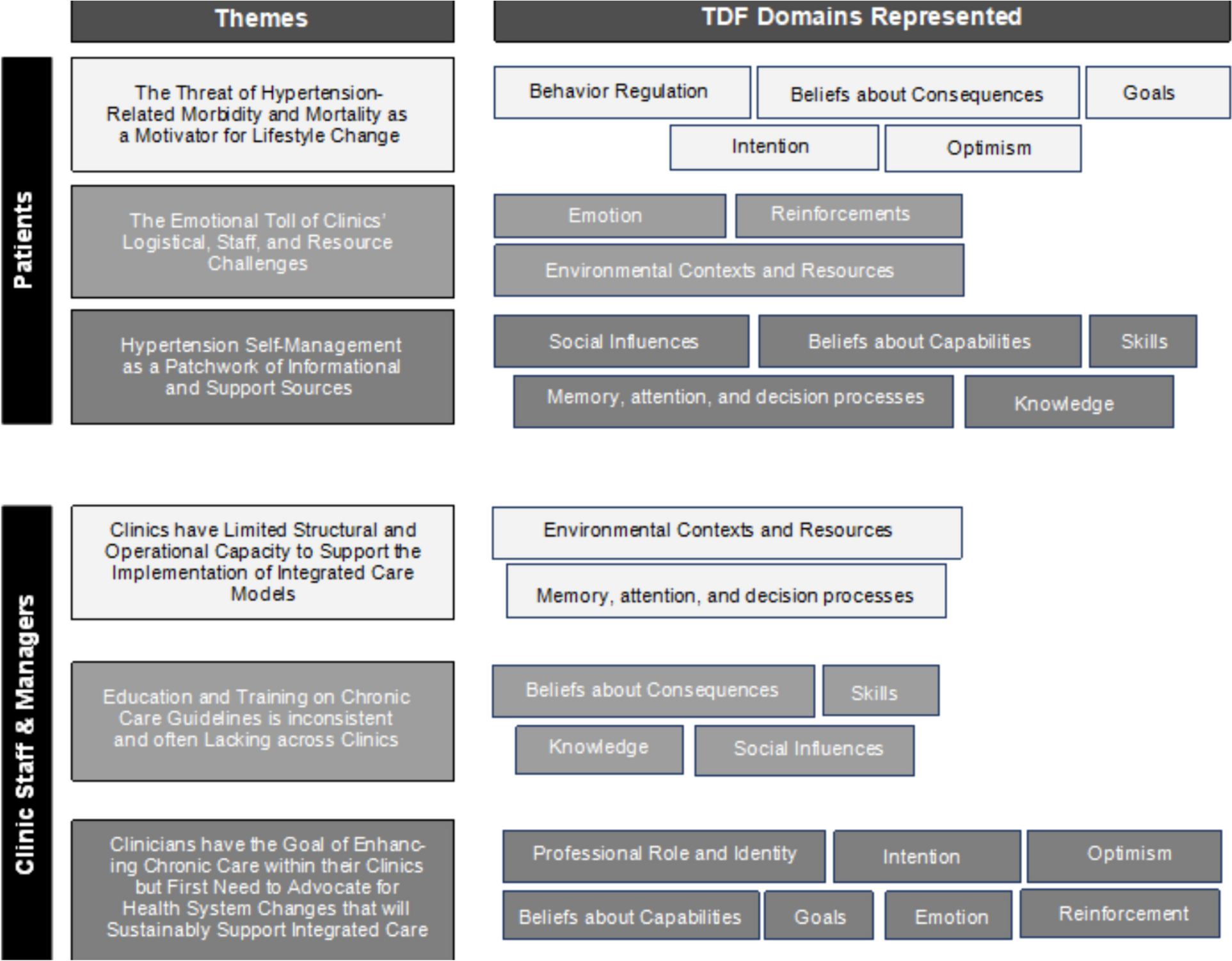

World AIDS Day 2024: Multi-level perspectives on factors that impact hypertension screening, treatment, and management among people with HIV in South Africa

Published in Sustainability, Biomedical Research, and General & Internal Medicine

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, and people living with HIV are at a higher risk. One major risk for cardiovascular disease is high blood pressure (i.e., hypertension), but many people with HIV, especially in South Africa, don't get the care they need for it. While there are guidelines for diagnosing and treating hypertension, routine blood pressure checks are often lacking. Since many people with HIV are already receiving care, combining hypertension treatment with HIV care could help improve health outcomes for this population.

What led to this study?

Our team interviewed and held group discussions with clinic staff and patients to understand the challenges and needs for better managing hypertension alongside HIV care. This study reports key factors that affect the way hypertension care is delivered, such as knowledge, support, and social and environmental influences that impact patients’ engagement with care. The findings will help develop better strategies to improve care by addressing the barriers and leveraging strengths identified in the healthcare system and community.

Why is this study important?

Despite hypertension being a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, most people with HIV do not receive the recommended screening and treatment. Addressing hypertension alongside HIV care could significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and improve overall health outcomes, but there is not enough theory-driven research to create feasible and effective strategies for combining hypertension and HIV care in resource limited settings in a way that fits the specific needs of different clinical actors and people affected by these conditions. The findings from this study will help guide the design of more effective healthcare strategies and interventions, ensuring better care for people with HIV while optimizing the use of available healthcare resources.

Did this study find any differences between perspectives of different stakeholders?

One unexpected difference between the two groups was their view on the seriousness of the diseases. Patients seemed to think hypertension was more urgent, while clinic staff felt that treating HIV should be the main focus for people dealing with both conditions. Overall, the study emphasizes the need for better education for both patients and healthcare workers about hypertension and highlights the importance of improving healthcare systems to better manage both conditions.

What is the wider significance of the study findings?

Both patients and clinic staff pointed out that a lack of proper facility resources and clinic organization made it difficult to regularly check and treat high blood pressure. Many staff members also felt they didn’t have enough training on how to care for chronic conditions like high blood pressure. Despite these challenges, there was strong support among clinical actors for combining HIV and hypertension care. Staff suggested incorporating a stronger focus on chronic disease care in regularly held clinical trainings, providing additional resources, and offering rewards to motivate staff. However, they stressed that for this to work long-term, bigger changes are needed in the healthcare system. Interviews with people living with HIV and hypertension revealed key insights into their experiences with managing their condition. Many patients were motivated to change their lifestyle because they feared serious health problems, like strokes, caused by uncontrolled hypertension. However, they often found clinics difficult to navigate due to long wait times and lack of organization. Additionally, patients managed their condition with the help of family and community groups, but most expressed a need for more guidance and tools, like blood pressure machines, to help them monitor their health at home.

How were these findings used to inform future work?

A broader stakeholder group provided input on these data, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of how hypertension care could be improved in the South African context. Participatory research methods were then used to inform the design of implementation strategies aimed at promoting the adoption and implementation of guideline-recommended hypertension screening and management practices in local primary care settings. By centering the design of those strategies on data collected in this study, our team aims to overcome challenges at the patient, provider, and clinic-level that may hinder improved cardiovascular disease control in this high-risk population.

Geldsetzer P, Manne-Goehler J, Marcus ME, et al. The state of hypertension care in 44 low-income and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative individual-level data from 1·1 million adults. Lancet. 2019, 394(10199):652-662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30955-9.

Wollum, A, Gabert R, McNellan CR, et al. Identifying gaps in the continuum of care for cardiovascular disease and diabetes in two communities in South Africa: Baseline findings from the HealthRise project. PLOS ONE. 2018; 13(3): e0192603.

Johnson LCM, Khan SH, Ali MK, et al. Understanding barriers and facilitators to integrated HIV and hypertension care in South Africa. Implement Sci Commun. 2024;5(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s43058-024-00625-5.

Follow the Topic

-

Implementation Science Communications

An official companion journal to Implementation Science and a forum to publish research relevant to the systematic study of approaches to foster uptake of evidence based practices and policies that affect health care delivery and health outcomes, in clinical, organizational, or policy contexts.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Advancing the Science and Metrics on the Pace of Implementation

The persistent 17-year span between discovery and application of evidence in practice has been a rallying cry for implementation science. That frequently quoted time period often implies that implementation needs to occur faster. But what do we really know about the time required to implement new evidence-based practices into routine settings of care. Does implementation take 17 years? Is implementation too slow? Can it be accelerated? Or, does a slower pace of implementing new evidence-based innovations serve a critical function? In many cases—pandemics, health inequities, urgent social crises—pressing needs demand timely implementation of rapidly accruing evidence to reduce morbidity and mortality. Yet many central tenets of implementation, such as trust, constituent inclusion, and adaptation, take time and may require a slow pace to ensure acceptability and sustained uptake.

To date, little attention and scant data address the pace of implementation. Speed is a rarely studied or reported metric in implementation science. Few in the field can answer the question, “how long does implementation take?” Answering that question requires data on how long various implementation phases take, or how long it takes to achieve implementation outcomes such as fidelity, adoption, and sustainment. Importantly, we lack good data on how different implementation strategies may influence the amount of time to achieve given outcomes.

To advance knowledge about how long implementation takes and how long it “should optimally” take, this collection seeks to stimulate the publication of papers that can advance the measurement of implementation speed, along with the systematic study of influences on and impacts of speed across diverse contexts, to more adequately respond to emerging health crises and benefit from emerging health innovations for practice and policy. In particular, we welcome submissions on 1) methodological papers that facilitate development, specification, and reporting on metrics of speed, and 2) data-based research (descriptive or inferential) that reports on implementation speed metrics, contextual factors and/or active strategies that affect speed, or the effects of implementation speed on important outcomes in various contexts.

Areas of interest include but are not limited to:

• Data based papers documenting pace of moving through various implementation phases, and identifying factors (e.g., implementation context, process, strategies) that affect pace of implementation (e.g., accelerators and inhibitors)

• Data based papers from multi-site, including multi-national, studies comparing pace of innovation adoption, implementation, and sustainment across various contexts

• Data based papers reporting time to implementation in the face of urgent social conditions (e.g., climate change, disaster relief) Papers on how to accelerate time to delivery of treatment discoveries for specific health conditions (e.g., cancer, infectious disease, suicidality, opioid epidemic)

• Data based papers on the timeliness of policy implementation, including factors influencing the time from data synthesis to policy recommendation, and from policy recommendation to implementation

• Span of time needed to: achieve partner collaboration, including global health partnerships adapt interventions to make them more feasible, usable, or acceptable achieve specific implementation outcomes (e.g., adoption, fidelity, scale-up, sustainment) de-implement harmful or low-value innovations, or to identify failed implementation efforts

• Effect of implementation pace on attainment of key outcomes such as constituent engagement, intervention acceptability or sustainability, health equity, or other evidence of clinical, community, economic, and/or policy benefits.

• Papers addressing the interplay between pace and health equity, speed and sustainability, and other considerations that impact decision-making on implementation

• Methodological pieces that advance designs for testing speed or metrics for capturing the pace of implementation

• This Collection welcomes submission of a range of article types. Should you wish to submit to this Collection, please read the submission guidelines of the journal you are submitting to Implementation Science or Implementation Science Communications to confirm that type is accepted by the journal you are submitting to.

• Articles for this Collection should be submitted via our submission systems in Implementation Science or Implementation Science Communications. During the submission process you will be asked whether you are submitting to a Collection, please select "Advancing the Science and Metrics on the Pace of Implementation" from the dropdown menu.

• Articles will undergo the standard peer-review process of the journal they are considered in Implementation Science or Implementation Science Communications and are subject to all of the journal’s standard policies. Articles will be added to the Collection as they are published.

• The Editors have no competing interests with the submissions which they handle through the peer-review process. The peer-review of any submissions for which the Editors have competing interests is handled by another Editorial Board Member who has no competing interests.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in