The Not-So-Hidden Architecture of Our Choices

Published in Social Sciences, Public Health, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Many people believe that their daily decisions, such as what they eat, what they buy, and how they act, are driven by willpower or good intentions. However, behavioural research paints a much more complex and interesting picture.

Studies that combine packaging experiments and memory tasks have shown that 42% of supermarket food choices are made in less than five seconds. These choices are often prompted by what scientists call a cue, which refers to any trigger in our environment, including a sight, sound, place, or feeling, that prompts us to act, sometimes before we even realise it is happening 1,2. In those moments, something as simple as the colour of a box, the shape of a package, or a familiar logo can serve as a powerful signal, helping to set routines and build habits almost without our conscious awareness.

Marketing research is not just about selling products. It is about understanding how our surroundings and the cues found within them become a kind of invisible architecture, quietly shaping our daily routines and decisions. Marketers have long studied how cues turn into habits, and these same behavioural principles can be applied just as powerfully to public health, especially when designing interventions to improve population well-being 3,4. When we understand this architecture and learn to see the forces that drive us, we gain the tools to build better habits for both individuals and society as a whole.

The Hidden Power of Cues and Hooks

Not all cues are equally influential. Some cues are so powerful that researchers describe them as Unhealthy Habituation Hooks (UHHs). This concept refers to specific cues, situations, feelings, or routines, such as being at a party, feeling bored or stressed, walking past a bakery at a particular time, or seeing snacks and soda in a familiar kitchen spot. These UHHs can make unhealthy choices feel automatic and can often occur before we have the opportunity to think about or recall our intentions 3.

For example, in a doctoral study from Australia, forty-four per cent of participants demonstrated mild habitual responses to these hooks, forty per cent were considered vulnerable, and sixteen per cent were classified as hazardous, meaning their unhealthy habits were very embedded and repeated within their routines. Notably, these numbers closely match national obesity rates, indicating a strong link between habitual cues and population-level health outcomes 3,5. In those studies, when people were presented with the simple scenario of a party, almost everyone chose the cue ‘crisps’ as their snack, regardless of how committed they claimed to be to healthy eating 3.

When Good Intentions Meet Automatic Routines

It is one thing to know what is healthy, but actually doing it, especially when routines and emotions are involved, is a much greater challenge than it may seem. The numbers are compelling. When people feel bored, sad, or are spending time with friends or at parties, which are all examples of cues or UHHs, between 68 and 76 per cent will choose processed snacks rather than something nutritious 3,4. This is a clear example of automaticity (also defined as semiconscious). Automaticity describes the process of repeating actions so frequently that we end up doing them without thinking, such as grabbing a salty snack every time we watch television or stopping for fast food every time we pass by and smell it from our favourite restaurants or bakeries 3.

Research using Bayesian analysis, which is a statistical approach that continually updates predictions as new evidence is gathered, has found that certain cue–food combinations, like feeling sad and selecting chocolate, occur eighty-eight per cent of the time, even among those who express a desire to change these habits 3. This finding aligns with broader literature on habit formation and health behaviour, where automatic responses are often shown to override conscious intentions 8.

Salience, Environments, and Building Better Defaults

Salience refers to how much something stands out and is remembered. Retailers use salience by placing snacks near checkouts, using bright colours, and playing catchy music, all to make certain foods the default or most frequent choice. Behavioural science suggests that we can use these strategies to design Healthy Habituation Hooks (HHHs), which are routines, cues, or environmental features that make healthy choices just as easy and automatic as unhealthy ones.

Imagine that fruit is always the first thing you see in your kitchen, that water bottles are readily available wherever you spend time, or that you have built a daily walk with a friend into your routine. These are all examples of HHHs, and evidence shows that they can be as powerful as unhealthy hooks when designed intentionally into our daily environments 3,4,5. Studies have confirmed that environmental and contextual changes are effective ways to shift health behaviour in a sustainable way 9,10.

Beyond Marketing: The Science of Behaviour for Public Health

It is essential to recognise that marketing is, at its foundation, the study of behaviour and of the environments that influence our choices. The same cues, habits, and social influences that encourage us to buy snacks are also the driving forces behind our health decisions, our daily routines, and whether we stick to medical advice or not. For public health to be truly effective, it is necessary to borrow and adapt these behavioural techniques, not just to provide information or warnings, but to create environments in schools, clinics, offices, and homes where healthy actions are the easiest, most familiar, and most accessible options 11,12. Habits are not built by resisting automaticity, but by making healthy routines feel as natural as those that came before them.

Designing Age-Friendly and Enabling Environments

The impact of environments on behaviour is especially important when considering older adults and healthy ageing. University courses that examine enabling environments for older people now explore how physical, built, and social settings can support a healthy lifestyle throughout the life course. These approaches highlight that promoting healthy ageing is not only about personal choice, but also about how individuals interact with the opportunities and constraints of their surroundings. Concepts like person-environment fit (the match between a person’s abilities and the environment they live in) are fundamental for well-being, autonomy, and maintaining identity in later life 13.

Assessing environments for older people means looking beyond basic safety or accessibility and paying attention to cues and routines in daily life, such as access to walkable spaces, supportive social networks, healthy food within reach, or regular reminders to stay active. These real-world features can become Healthy Habituation Hooks, making beneficial choices feel natural, familiar, the easiest, and the most available options, helping older adults maintain independence and quality of life 13,14. Communities and health services can use these insights to help people of all ages and locations build and maintain healthy habits.

Smart Tools for Smart Human-Centred Environments

Today, smart digital tools like PROLIFERATE_AI are changing how we understand and support healthy behaviours, daily routines, and care 5,6. PROLIFERATE_AI works a bit like a smart assistant that keeps learning, using Bayesian analysis (which means it updates its advice each time it gets new information about what people do). This tool is built using co-design, a process where real people from diverse fields and with varied experiences (patients, clinicians, and caregivers) help shape solutions from the outset, ensuring results align with real needs and experiences. It also considers sociodemographic segmentation (examining differences in age, culture, and background) to ensure recommendations are effective for everyone.

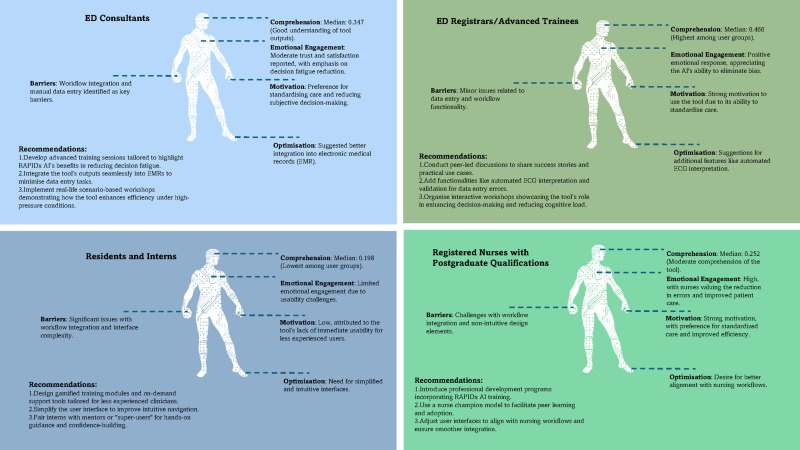

Unlike most methods that can rely solely on surveys, interviews or focus groups, PROLIFERATE_AI could utilise information from digital sources, such as wearable trackers, appointment reminders, or even video. This allows researchers to identify habits that people may overlook, such as how often someone stands up to move or whether a family regularly takes their medication. For example, in emergency heart care, PROLIFERATE_AI revealed that making the right decision depends not only on medical knowledge, but also on everyday routines, social characteristics, and the unique context of each person’s role 6. The same approach is now being tested in hospitals and learning settings, helping teams identify and improve the daily patterns that matter for both patients and staff.

The Environment Is Not Everything: Relationships Matter Most

Emergent research shows that simply having the best environment, new technology, or strong policies is not enough to create better patient outcomes. In a recent study from Spain and Australia, researchers collected feedback directly from patients and used a model called the Fundamentals of Care Framework to test what really made a difference 7. They found that environments only lead to better care when they help doctors, nurses, and health teams build strong, trusting relationships with patients. Using a method called Consistent Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (cPLS-SEM), they demonstrated that nearly half of the improvement in clinician–patient relationship quality in Australia was attributed to system-level support, whereas almost all gains from the integration of care outcomes were driven by the human relationship itself.

.jpg)

In other words, the most effective systems, policies, or digital workflows are those that empower staff to listen, connect, and respond to each person’s needs. This insight is also clear in digital health research. Tools such as telehealth, reminders, and digital dashboards make the biggest impact when they help patients and staff stay connected, support empathy, and enable teamwork (not just when they increase efficiency or gather more data) 6,7,11. When health services use real-time patient feedback and focus on the quality of relationships, they can spot which habits and routines make care better and where to improve.

For example, a digital dashboard with new metrics might reveal that patients feel more supported when they see the same nurse regularly, or that a simple reminder with educational strategies helps families stick to medication schedules 7,10,15,16. Altogether, these digital and analytic advances are helping build a future where health systems are not just efficient or safe, but truly centred on the real needs and relationships of people. This means healthy, person-centred behaviours become the easiest, most familiar, and most available choices for everyone.

Supporting the Creation of Healthy Habits for Everyone

If we have learned habits that make reaching for snacks or sugary drinks easy and routine, we can also intentionally create habits that make healthy choices feel natural, familiar, and the most available option. The process begins by recognising unhealthy habituation hooks, which are cues and routines that unconsciously steer people toward unhealthy behaviours. These might include the placement of junk food at eye level, colourful packaging, or social situations where unhealthy choices are encouraged.

Real and lasting change happens when we actively obstruct these unhealthy hooks, making them less prominent or accessible, and at the same time, facilitate healthy habituation hooks. This means designing our environments and daily routines so that positive cues are more visible and appealing, healthy actions feel easier and more familiar, and opportunities for making healthy choices are always accessible. Importantly, these cues and supports can be strengthened through positive relationships and social networks, as well as by leveraging new digital health technologies.

Australia’s tobacco control strategy is a compelling example of how policy, environment, and social supports can work together to enable healthy choices. When Australia removed branding from cigarette packs, introduced plain packaging, and banned smoking in hospitals, entrances, and public spaces, these actions broke the automatic cues that made smoking feel routine for many people 17. This not only reduced the visual appeal and habitual triggers associated with smoking, but also made smoke-free environments feel like the most natural, familiar, and easy choice for everyone. These changes reached across all ages, locations, workplaces, schools, and hospitals, supporting those who were already motivated to quit and establishing a healthier default for the entire population.

This approach demonstrates that reshaping cues and environments is a practical and evidence-based public health strategy for building healthier habits at scale. As we look to the future, there are new opportunities to amplify these effects by connecting positive social relationships with advances in digital health technologies, including artificial intelligence. Digital health platforms, smart devices, and AI-powered applications can act as enablers, helping people notice healthy options, receive timely reminders, and access personalised support that makes healthy routines more salient, easier to maintain, and better integrated into daily life. These innovations can foster supportive health behaviours, services, relationships and communities, making it even more likely that healthy choices and caring behaviours become second nature, accessible to everyone, and sustained over time 6,7,18,19.

References

1. Piñero de Plaza, M.A., et al., 2010. Distinctive elements in packaging (FMCG): an exploratory study. In: ANZMAC 2010: Doing More with Less. Proceedings of the 2010 Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference. Christchurch, NZ: ANZMAC.

https://www.anzmac2010.org/proceedings/pdf/anzmac10Final00335.pdf

2. Piñero de Plaza, M.A., et al., 2012. A new behavioral methodology: measuring the effect of packaging design on shopper's memory. In: Muratovski G, editor. Design for Business. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/D/bo20662021.html

3. Piñero de Plaza, M.A., 2016. The semiconscious choice of food as a potential obesogenity marker [dissertation]. Melbourne: Deakin University.

https://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30090810

4. Pinero de Plaza, M.A., et al., 2021. Investigating salience strategies to counteract obesity. Health Promotion International, 36(6):1539-1553.

https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa123

5. Pinero de Plaza, M.A., et al., 2023. Co-designing, measuring, and optimizing innovations and solutions within complex adaptive health systems. Frontiers in Health Services, 3:1154614.

https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2023.1154614

6. Pinero de Plaza, M.A., et al., 2025. Human-centred AI for emergency cardiac care: evaluating RAPIDx AI with PROLIFERATE_AI. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 196:105810.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2025.105810

7. Pinero de Plaza, M.A., et al., 2025. Piloting structural equation modeling for fundamental care decision-making across healthcare settings. Research Square [Preprint], 2025 Apr 3.

https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6365026/v1

8. Marteau, T.M., et al., 2012. Changing human behavior to prevent disease: the importance of targeting automatic processes. Science, 337(6101):1492–5.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1226918

9. Hollands, G.J., et al., 2013. Altering micro-environments to change population health behaviour: towards an evidence base for choice architecture interventions. BMC Public Health, 13:1218. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1218

10. Thaler, R.H., Sunstein, C.R., 2009. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New York: Penguin Books. 2009 Feb 24.

https://www.amazon.com.au/Nudge-Improving-Decisions-Health-Happiness/dp/014311526X

11. Michie, S., et al., 2011. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6:42.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

12. Lawton, M.P., Nahemow, L., 1973. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfer C, Lawton MP, editors. The psychology of adult development and aging. Washington, DC: APA, pp. 619–74. https://awspntest.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F10044-020

13. World Health Organization, 2007. Global age-friendly cities: a guide. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547307

14. Kitson, A., et al., 2013. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(1):4–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06064.x

15. Institute of Medicine, 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027

16. Mudd, A., et al., (2023). The use of digital technologies in the inpatient setting to promote communication during the early stage of an infectious disease outbreak: a scoping review. Telemedicine and E-Health, 29(2), 172-197. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0615

17. Australian Government Department of Health, n.d. Tobacco control key facts and figures.

https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/tobacco-control-key-facts-and-figures?language=en

18. Wakefield, M.A., et al., 2013. Introduction effects of the Australian plain packaging policy on adult smokers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 3(7):e003175.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003175

19. Hammond, D., 2014. Standardized packaging of tobacco products: evidence review. London: Department of Health, UK Government. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/22106/1/Standardized-Packaging-of-Tobacco-Products-Evidence-Review.pdf

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in