A flicker of hope for an endangered flycatcher

Published in Ecology & Evolution

We’ve all heard the horror stories resulting from the climate crisis: emaciated polar bears staggering across barren ground formally covered by sea ice, giraffes dying from dehydration at Kenyan watering holes that now run dry, and scorched kangaroos fruitlessly trying to flee bushfires ravaging the Australian continent. In the midst of these harrowing tales, we often think of plants and animals as static entities that are helpless in the face of human-induced climate change. Indeed, when confronted with extreme weather events that are becoming increasingly common due to the climate crisis, they often are. However, organisms have a few tools at their disposal that can help mitigate the effects of altered environmental conditions.

One of the mostly widely documented ways in which species can cope with rising global temperatures is by shifting their geographic distributions to maintain the range of environmental conditions they’re used to experiencing (1). For example, butterfly communities across Europe have shifted northward by an average of 114 km from 1990-2008 in response to temperature increases (2). Alternatively, species can respond to climate change by remaining in place and adapting to changing environmental conditions. While evolution is known to occur over rapid timescales, clear examples of genetic adaptation to climate change in wild populations remain surprisingly limited (3).

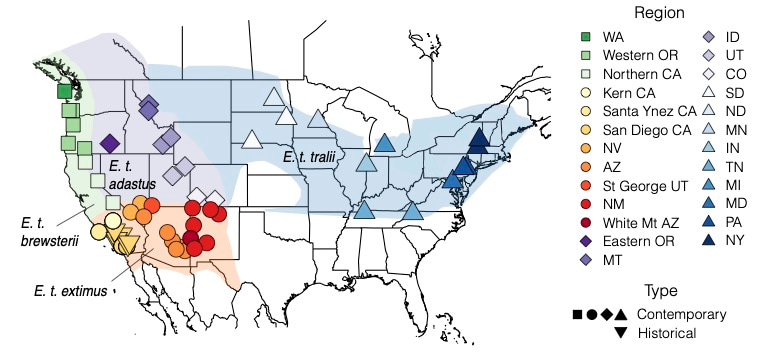

Our recent paper takes advantage of a rare collection of historical museum specimens dating back to the late 1800s to investigate evolutionary adaptation to climate change in the southwestern willow flycatcher, a bird of conservation concern. The willow flycatcher is comprised of four subspecies that breed throughout the United States and Canada. The southwestern subspecies, which inhabits southern California and the desert southwest, was listed as federally endangered in 1995 following precipitous population declines. To investigate changes over time in genes linked to climate adaptation in this endangered subspecies, we collaborated with museums, government agencies, and nonprofits to sequence the DNA of 17 historical birds collected near San Diego, California from 1888-1909 and over 200 contemporary willow flycatchers from across the breeding range, including 18 birds sampled near San Diego from 2010-2011.

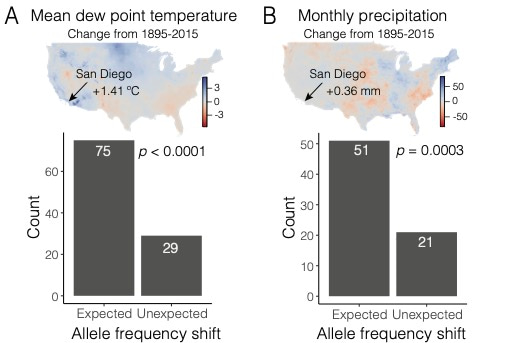

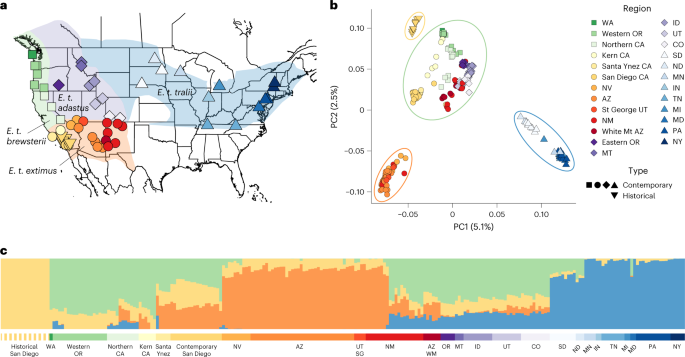

First, we compared the historical and contemporary individuals from San Diego to examine genome-wide shifts in genetic structure that have taken place within this population. While willow flycatcher populations have largely remained stable throughout the 20th century, we documented the movement of genetic material from neighboring populations in the Pacific northwest and desert southwest into San Diego over the past century. Next, we used the contemporary samples to scan the genome for genetic regions associated with important environment variables, such as precipitation and temperature, that affect willow flycatchers. After identifying regions of the DNA that are likely involved in climate adaptation, we extracted the genetic information from these regions in the historical and contemporary San Diego samples. We analyzed whether genetic variation at these loci has increased over time and whether these particular genetic variants associated with climate variables have shifted from the past to the present in order to adapt to wetter, more humid climate conditions in southern California.

When comparing current samples to individuals collected in the late 1800s, we documented an increase in genetic diversity at genes linked to climate adaptation, suggesting that the contemporary San Diego population is better able to adapt to changing environmental conditions. In addition, the genetic regions associated with mean dew point temperature (related to the moisture content in the air) and monthly precipitation have shifted in a direction consistent with climate adaptation in San Diego. Taken together, these findings suggest that willow flycatchers in southern California have some capacity to adapt to changing climate conditions over a century-long timescale. This evolutionary response was likely aided by the introduction of new genetic material into San Diego due to mixing with neighboring populations, which increased adaptive capacity following population decline at the turn of the century.

Despite evidence for climate adaptation, the future is not entirely bright for willow flycatchers breeding in southern California. In fact, the number of willow flycatcher breeding territories continues to steadily decline in San Diego (4), likely as a result of additional stressors such as habitat loss and brood parasitism (5). Thus, continued habitat restoration efforts will be necessary to save this population from extinction. More broadly, however, this study provides a glimmer of hope for organisms faced with changing climate conditions. In particular, we show that the mixing of genetically distinct populations can increase adaptive potential and likely facilitate species responses to climate change. Assisted gene flow, a conservation strategy that introduces new genetic diversity into vulnerable populations, may therefore give organisms a leg (or wing) up in the fight against climate change.

- Hoffmann, A. A. & Sgrò, C. M. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470, 479–485 (2011).

- Devictor, V., Van Swaay, C., Brereton, T., Brotons, L., Chamberlain, D., Heliölä, J., Herrando, S., Julliard, R., Kuussaari, M., Lindström, Å. and Reif, J., Differences in the climatic debts of birds and butterflies at a continental scale. Nature Clim Change 2, 121–124 (2012).

- Catullo, R. A., Llewelyn, J., Phillips, B. L. & Moritz, C. C. The Potential for Rapid Evolution under Anthropogenic Climate Change. Curr Biol 29, R996–R1007 (2019).

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus). 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. Arizona Ecological Services, Phoenix, AZ (2014).

- Kus, B. E., Beck, P. P. & Wells, J. M. Southwestern Willow Flycatcher populations in California: distribution, abundance, and potential for conservation. Avian Biol. 26, 12–21 (2003).

Banner image by Susan Logan Ward.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Climate Change

A monthly journal dedicated to publishing the most significant and cutting-edge research on the nature, underlying causes or impacts of global climate change and its implications for the economy, policy and the world at large.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in