How well do we learn from the past?

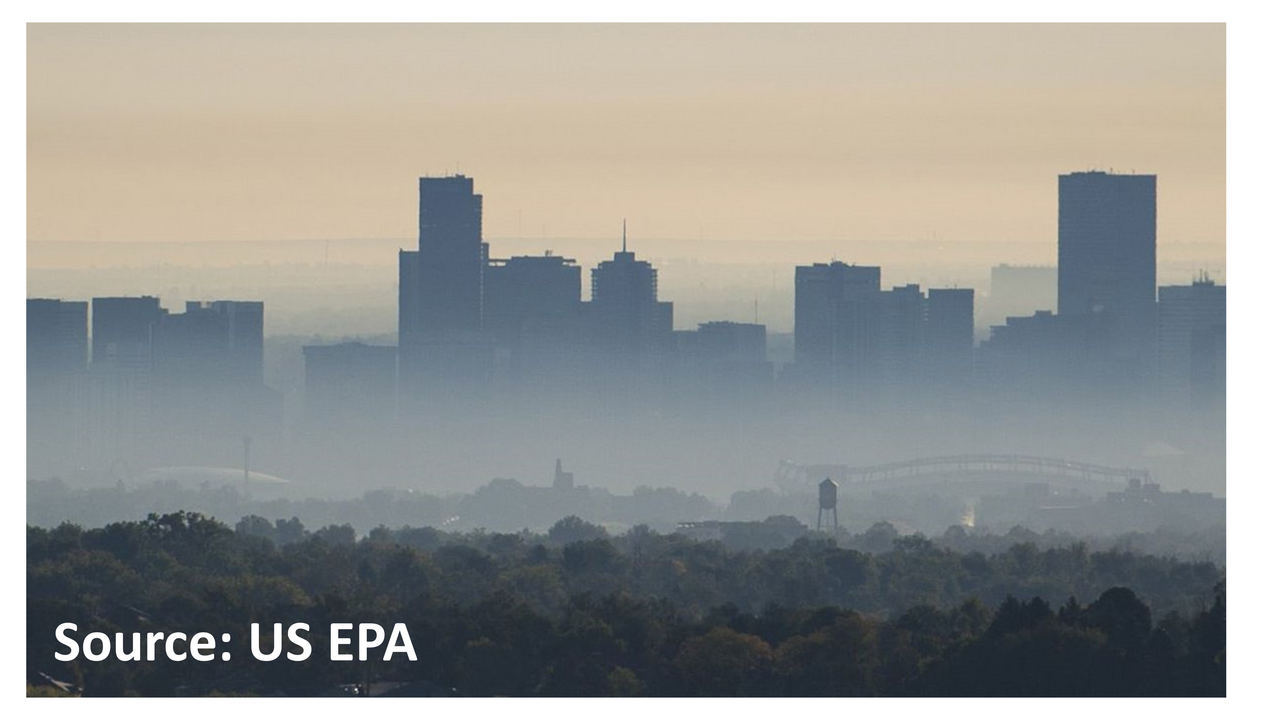

Air pollution and degraded air quality are direct products of human activity. People of a technological and scientific tendency are continuously trying to improve the standard of living for all. There is no question that we live better and longer than those living 100 and 200 years ago. But progress often exacts its toll, in this case air pollution. To provide the energy required to advance, fossil fuels are burnt and oxides of sulfur and nitrogen, airborne particulate matter, and much more. We have also created many useful chemical products, with associated emissions of pollution precursors like volatile organic compounds (VOCs). In retrospect, the process is clear – unregulated industrial progress creates greater emission of air pollutants. These increased air pollution levels degrade air quality and lead to greater adverse health outcomes, which leads to greater cost to society.

This pattern played out most dramatically in industrial centers in Western Europe and North America in the second half of the 20th century. Air pollution was a major problem in London, Paris, New York City, Los Angeles, and elsewhere. Fortunately, by the 1970s, 80s, and 90s these countries were affluent enough to do something about pollution, and politicians were enlightened enough to take action to improve the environment, for example the Clean Air Acts in the US. Pollution control regulations and fuel switching have resulted in air quality improvements for those countries that implemented regulations.

Meanwhile rapidly growing economies in parts of Asia, Africa, and South America were undergoing significant industrial progress and improvements in standard of living. Here’s where the history comes in. The kinds of large and mostly unregulated emissions that caused the poor air quality in Western Europe and North America in the 60’s through 90’s were experienced by developing economies in the 90’s through 2010’s. Rapid industrialization with the accompanying growth in power production – often from coal-fired power plants, created unhealthy air quality in many major urban areas in developing countries. Pollutants that have been hardest to control are ground level ozone and airborne particulate matter (PM2.5, which is particulate matter with effective diameter less than 2.5 micrometers). High ozone days occur most frequently in the NYC area on hot and stagnant summer days. These meteorological conditions are also conducive to high PM2.5 concentrations, and high ozone and PM2.5 often co-occur under these conditions.

Our paper uses the contrasts in the relationship of these pollutants in the megacities of New York in North America and Beijing in China. While New York City still suffers from poor air quality numerous times each year, it is far cleaner than it was in the 60’s through 80’s. Over the past twenty years (essentially 2001-2020) there has been a consistently monotonic relationship between the two pollutants, with an increasing slope on the linear term of the relationship and a decreasing coefficient on the exponential term. Our interpretation is that the slope describes the co-occurrence of the ozone and PM2.5 pollutants, and an increasing slope indicates a weaker control on ozone than for PM2.5. The power law exponential term, which becomes dominant and turns the relationship over at high PM2.5 levels, describes the suppression of ozone formation by high PM2.5.

The relationship of these pollutants in current Beijing is more looks like the 2000’s NYC, and our paper proposed the regional equal percentage emission reductions to balance the reduction of these two pollutants. Based on the model simulation, we suggest a 42% equal percentage reduction of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei regional emissions as a goal for the 2019 Beijing PM2.5 dropping to the 2001 NYC level, 53% to reach the O3 concentration below China’s O3 standards (75 ppb), and 70% for Beijing PM2.5 reach the 2019 NYC levels.

This recognition of the interaction between these two impactful pollutants, and the lessons that can be learned when analyzing pollutant relationships at these two megacity regions give this work added importance.

Follow the Topic

-

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science

This journal is dedicated to publishing research on topics such as climate dynamics and variability, weather and climate prediction, climate change, weather extremes, air pollution, atmospheric chemistry, the hydrological cycle and atmosphere-ocean and -land interactions.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Modeling of Airborne Composition and Concentrations

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Inter-Basin Dynamics: Cross-Ocean Interactions and Decadal Forecasting

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in