Application of wearable smart devices in investigating the effects of air pollution on atrial fibrillation onset

Published in Healthcare & Nursing

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death globally, with atrial fibrillation (AF) being the most common type of cardiac arrhythmia. AF is characterized by irregular and rapid contraction of the atria, leading to insufficient blood pumping and an increased risk of CVD and stroke. Air pollution, on the other hand, is a major environmental risk factor for CVD, with particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), and other air pollutants having a significant impact on CVD mortality and morbidity. Although some studies have explored the associations between air pollution and daily AF emergency visits and/or hospital admissions, studies based on individual-level information, and those at finer exposure time windows are relatively scarce.

The clinical diagnosis of AF requires relatively complex examinations such as 12-lead electrocardiogram and echocardiography. However, the atypical symptoms of AF, intermittent occurrence, and limitations of timely electrocardiogram diagnosis have led to a low diagnosis rate, making it a challenge to manage potential AF patients. With the popularity of wearable devices such as wristwatches and smart bracelets in recent years and the advancement of photoplethysmography (PPG) diagnostic technology, wearable smart devices have become applicable for earlier identification and monitoring of AF events in large-scale population samples using.

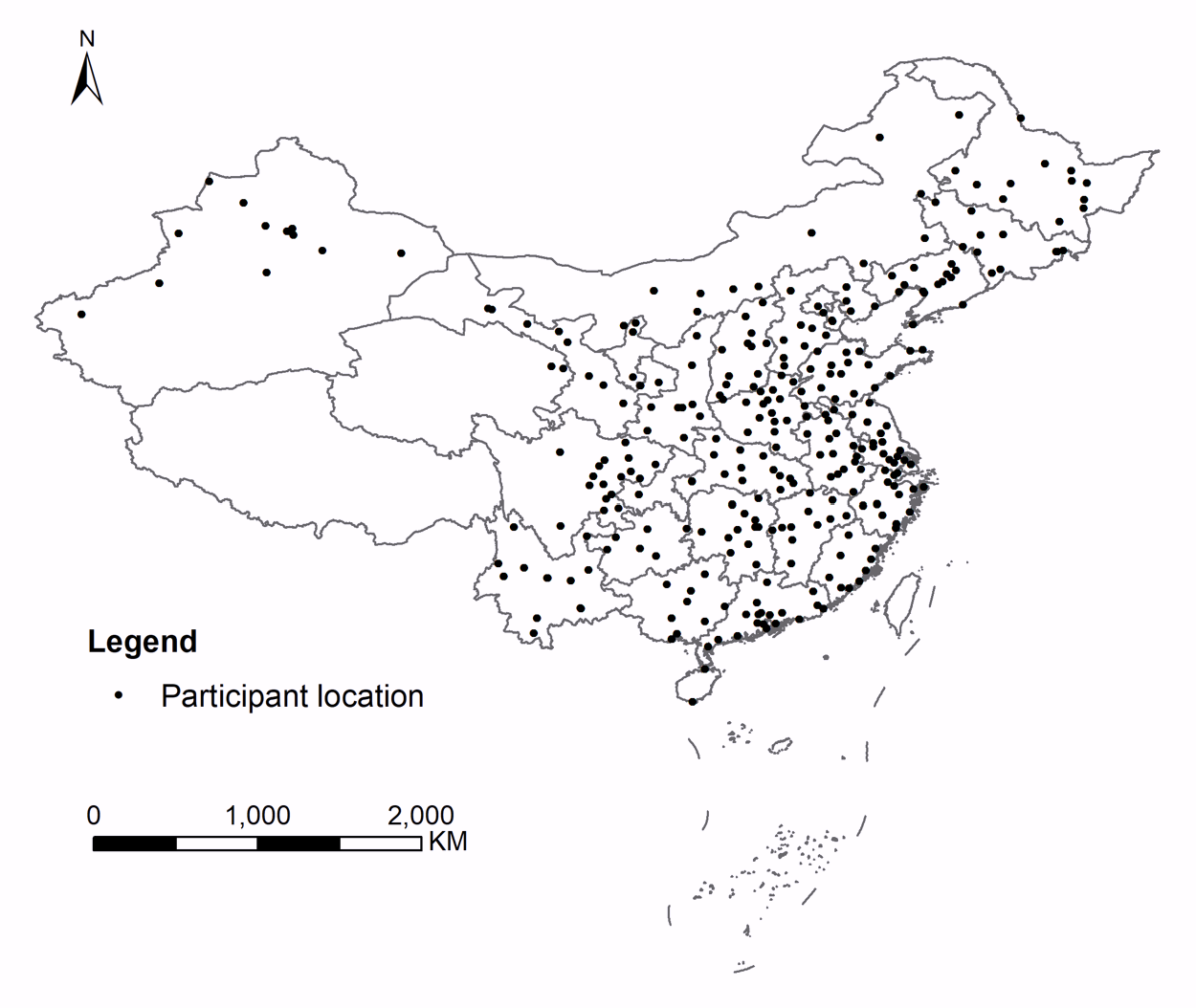

In a recent study, pulse wave records from wearable smart devices such as Huawei watches and Honor bracelets were collected from participants with potential cardiovascular risks between 2018 and 2021 (Figure 1). The study screened 11,906 AF events in 2,976 individuals from 288 cities in China using a highly accurate (>91%) PPG diagnostic method. Exposure level of six criteria air pollutants were matched at an hourly scale. The study used a time-stratified case-crossover study design to explore the association between short-term exposure to air pollution and AF events, employing conditional logistic regression models.

Figure 1. Locations of study participants

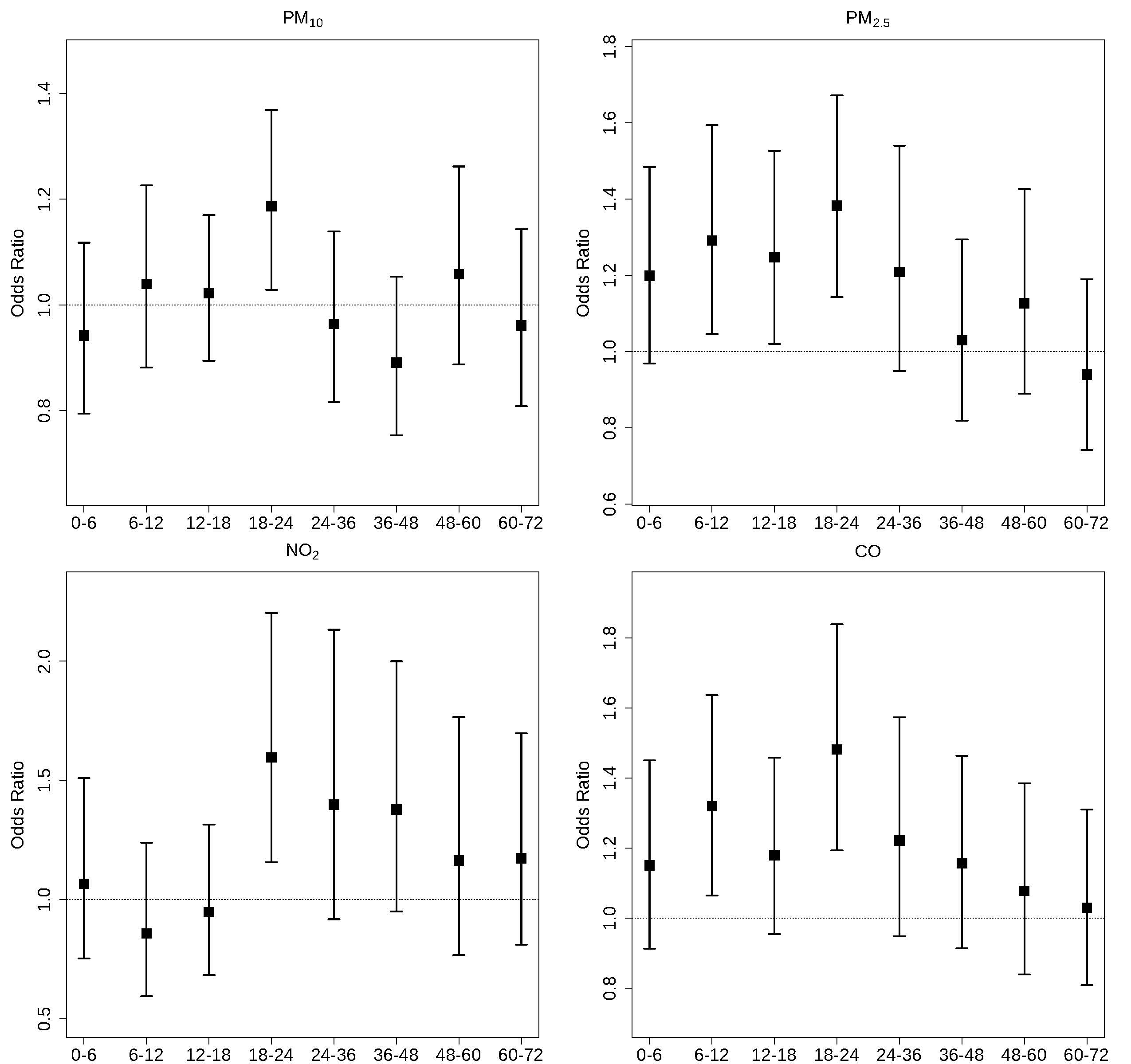

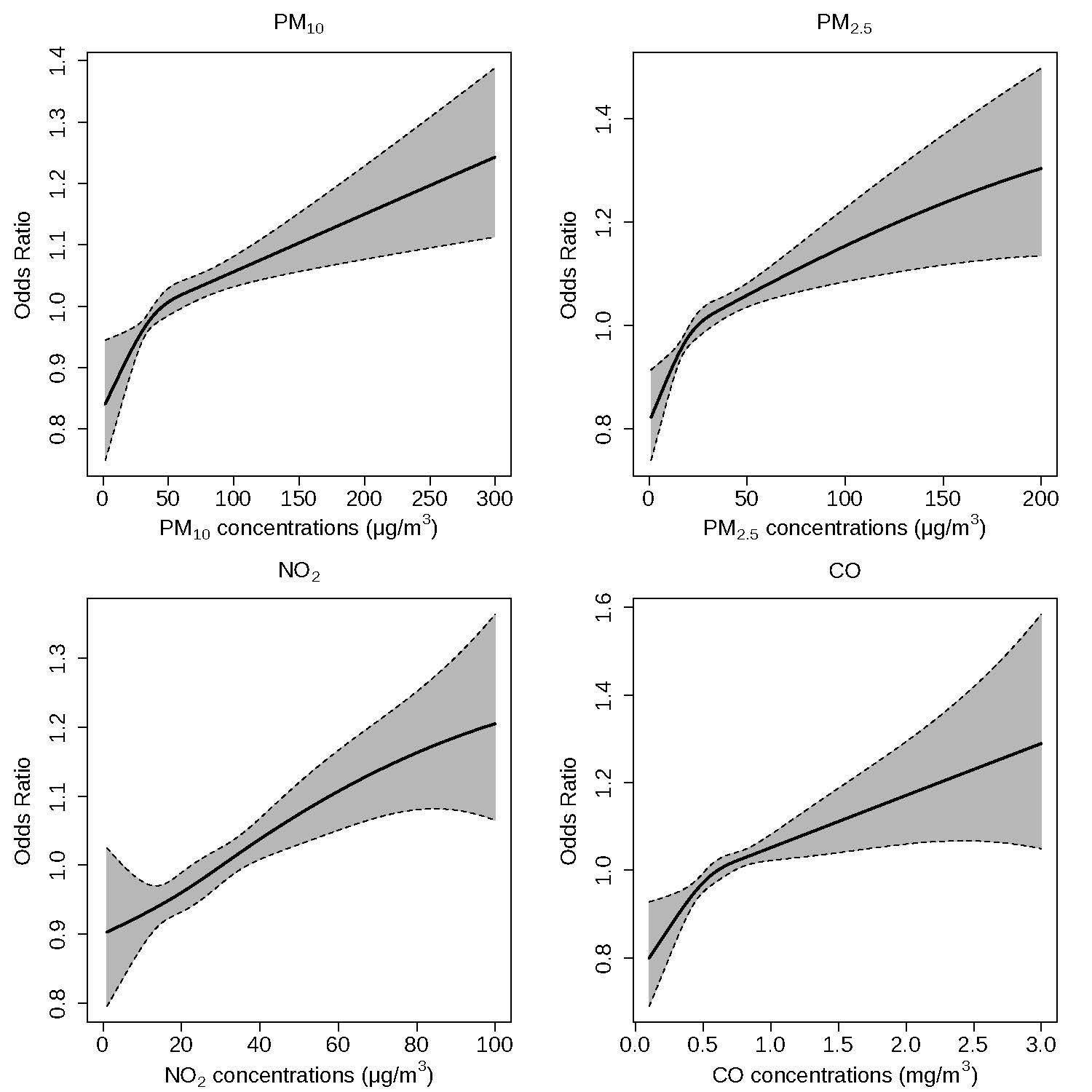

The study found that acute exposure to air pollution can significantly increase the risk of AF events, with the strongest effect observed in the time interval of lag 18-24 hours (Figure 2). For an interquartile range increase in PM10, PM2.5, NO2, and CO concentrations, the odds ratio (OR) for AF events were 1.19 (1.03, 1.37), 1.38 (1.14, 1.67), 1.60 (1.16, 2.20), and 1.48 (1.19, 1.84), respectively. The exposure-response relationship curves for the above air pollutants and AF events showed a linear pattern without an obvious threshold, and with a steeper slope in lower concentration ranges (Figure 3). In the two-pollutant model, the above associations remained robust to adjustment of co-pollutants. Furthermore, stratified analysis results showed that air pollution had a more significant impact on AF events in female, elderly, and cold-season populations.

Figure 2. Associations between air pollutants and atrial fibrillation at different time windows.

In conclusion, this nationwide multicenter study shows a significant association between hourly-level air pollution exposure and acute AF events. The study highlights the need for stronger air pollution control measures and provides evidence of the feasibility and effectiveness of using wearable devices and PPG diagnostic technology in environmental and health research. These findings have important implications for public health policy and the prevention and control of CVD.

Figure 3. Exposure-response curves for air pollutants and atrial fibrillation

Follow the Topic

-

npj Digital Medicine

An online open-access journal dedicated to publishing research in all aspects of digital medicine, including the clinical application and implementation of digital and mobile technologies, virtual healthcare, and novel applications of artificial intelligence and informatics.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Evaluating the Real-World Clinical Performance of AI

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 03, 2026

Impact of Agentic AI on Care Delivery

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jul 12, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in