Can We Disrupt the “Climate-Debt Doom Loop” in U.S. Cities?

Published in Earth & Environment, Economics, and Law, Politics & International Studies

What inspired this paper?

During Climate Week last fall, I was invited to a Chatham-style roundtable at the New York Stock Exchange. The setting was an impressively interdisciplinary group of climate science experts, municipal advisors, bond analysts, insurance specialists, and real-estate researchers, all speaking candidly about something that is at the intersection of all of their work: physical climate risk and local public finance.

At this discussion, certain themes emerged amidst frustration, urgency, and jittery optimism (the latter most definitely by me). Physical climate risks are accelerating. Insurance markets are increasingly signaling distress through premia spikes or withdrawal. Real estate investors are adjusting their portfolios. And yet, municipal bond pricing remains largely unchanged in the context of climate risk (what an expert described as a “market failure in slow motion”). Even as early warning signals accumulate each year, the core financing for local infrastructure has stayed the same.

It was this roundtable discussion that ultimately sparked and shaped the conceptual foundation of this Nature Cities paper. My wonderful co-authors (a group of truly stellar individuals from many sectors and disciplines) and I zoomed out to ask: how might all of these system-wide signals fit together, and what might that mean for cities?

What did we do?

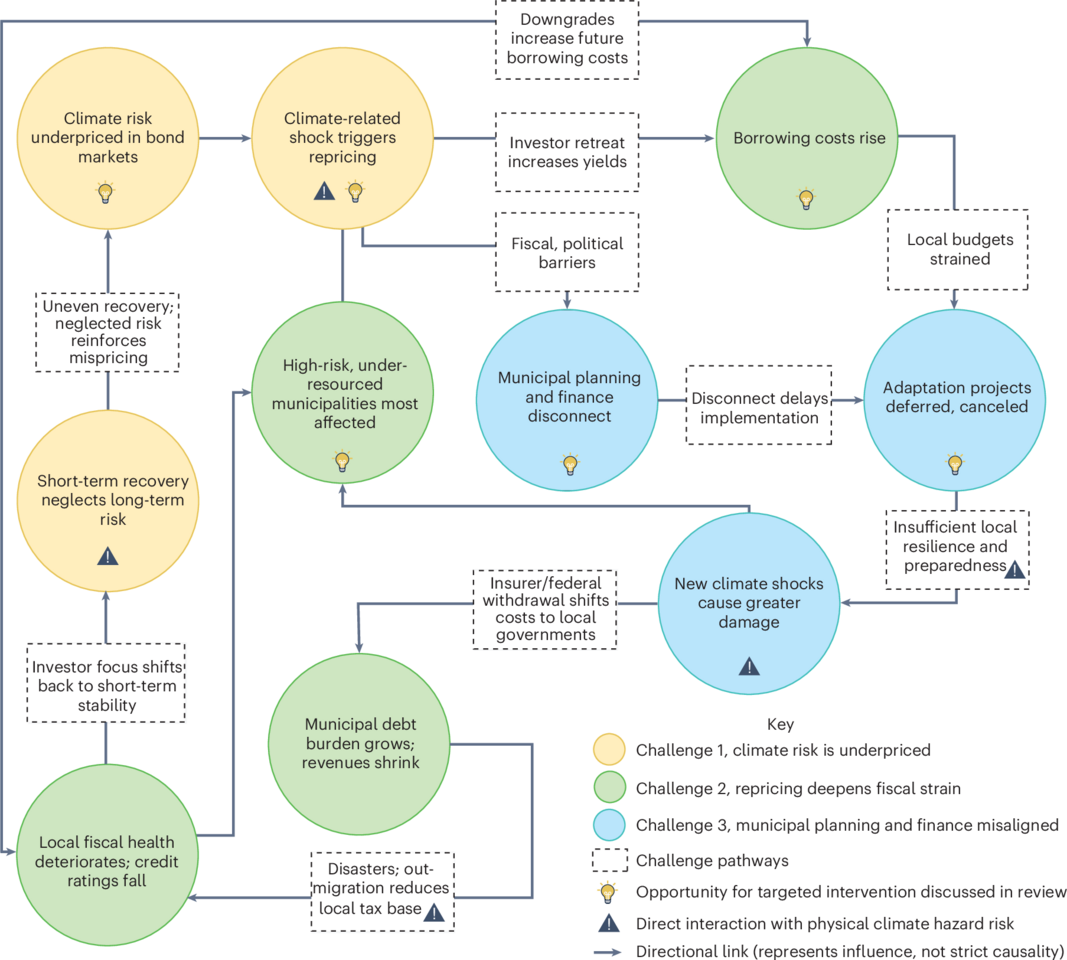

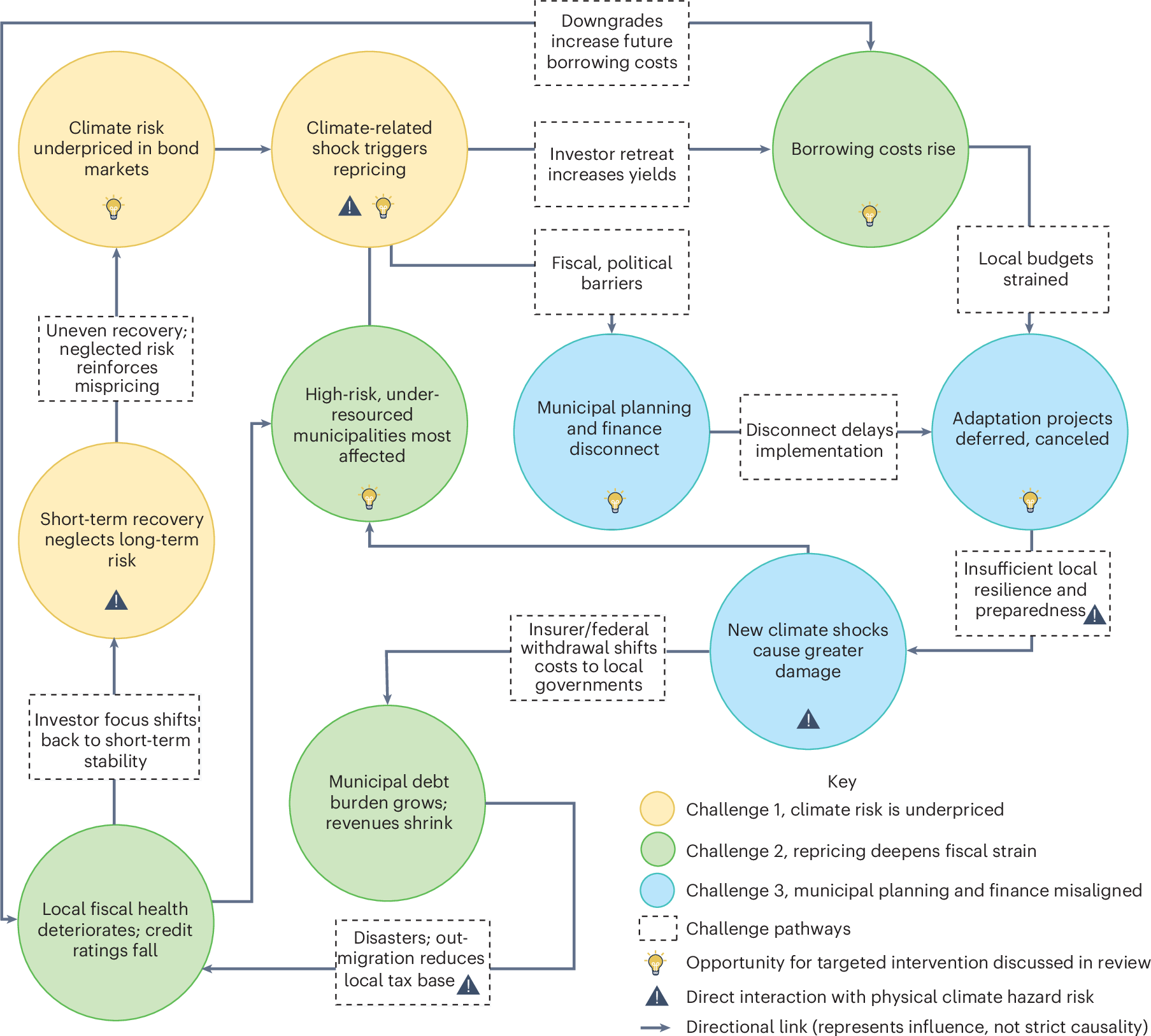

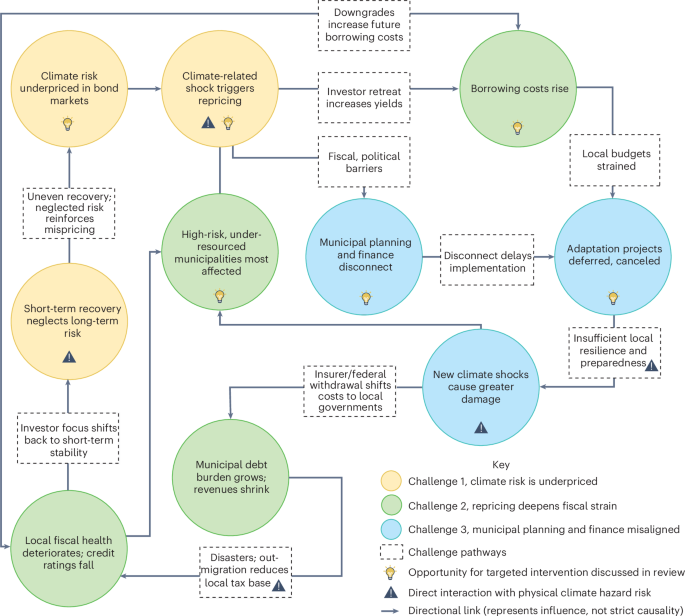

We derived research from climate science, municipal budgeting, credit ratings, insurance markets, migration, and infrastructure governance to understand why the signals around climate remain so muted in municipal finance (but are not so in other sectors such as insurance and real estate). After analyzing peer-reviewed works, local case studies, and institutional practices, we noticed a pattern: each sector was responding to climate risk in its own silo, so to speak, but none of them were accounting for how their decisions and timelines might compound one another over time. We developed the climate-debt doom loop for municipalities, (Figure 1 in the paper, reproduced below) a reinforcing cycle in which climate shocks strain local budgets, fiscal stress often delays adaptation, and deferred adaptation projects essentially amplify future losses, further straining local budgets.

Our goal is to show how these fragmented systems interact, where climate risk gets overlooked or underpriced, and what tools cities/institutions could use to disrupt the loop before the fiscal impacts deepen.

One key takeaway from this work is the value that two-way collaborations bring to the table. We see real-world practitioners are already experimenting with innovative climate-aware tools, while academic research helps stress-test and refine them. This paper’s authors had a strong mix of both groups and many in the middle, which helped ensure that our developed ideas were rigorous and implementable.

Why should you care?

If you, the reader, are based in the U.S., this issue affects you and I, our communities, our states, and our country, too. The $4 trillion U.S. municipal bond market finances over 70% of local public infrastructure, ranging from roads and bridges to water systems and public schools. As we discuss in our paper, physical climate risk is underpriced when assessing bond valuations in high climate risk areas. In other words, cities may be (unknowingly) financing long-term infrastructure under the assumption that there will be little to no climate risk exposing the projects. Further, investors (the actors that purchase the bonds) may be overlooking the risks that could become material a lot sooner than expected.

This is a discussion of when, not if. When investors begin to pay attention and incorporate climate risks into their decision-making adequately, borrowing costs will rise steeply in cities with high climate risk exposure and limited fiscal capacity. These are often the same cities that already struggle with underinvestment, aging infrastructure, and/or constrained budgets. As a result, when The Great Repricing occurs, it will deepen existing disparities, where well-resourced cities will weather the shift (pun intended), while under-resourced ones may fall further and further behind just when they need the investments the most

What do we do with this?

Once we connected these pieces, the problem looked different! So, instead of treating climate risk, credit ratings, insurance retreat, local fiscal stress, and adaptation gaps as separate issues, the doom loop framework shows how they are reinforcing one another in cities. Cities are facing climate hazards, yes, but also slow-moving financial norms, fragmentation in governance, and short-term planning which makes it harder to manage those hazards. Our frameworks help articulate why risks might stay invisible until they suddenly aren’t, and why under-resourced municipalities are most likely to face consequences when that shift happens.

I had the opportunity to attend a similar roundtable at NYSE this fall, too; this time, the conversations felt more urgent and targeted toward disclosure mandates, data standardization, and mitigating the “mess” that has emerged from misalignments between adaptation planning and municipal finance. At the same time, the solutions recommended during these discussions were a lot more focused, tangible, cost-effective, and realistic given the scale of the issue. We outlined some of these recommendations, too, from clearer climate disclosures to credit enhancement programs. Oftentimes, the policy recommendations can feel abstract and detached from reality. To counter this, we included real case studies that have successfully disrupted the doom loop to highlight that these solutions are feasible, reproducible, and likely successful (Figure 4 in the paper).

What comes next?

Meaningful progress will require multidisciplinary coordination, where we would ideally see city finance offices, credit analysts, insurers, planners, and researchers working from the same evidence base. Our paper is a step toward that shared language, especially regarding varying timescales each stakeholder might operate on, but implementation will indeed happen across sectors. As thinkers like Elinor Ostrom have reminded us all, many highly interconnected systems can become fragile if and when shocks cascade across sectors. This is precisely the challenge cities face when climate extremes intersect with finance and governance.

Ultimately, this paper is about emphasizing the opportunities for all municipal actors (city governments, investors, tax and ratepayers, etc.) to treat “resilience” as a strategic investment: one that can lower long-term costs, protect critical infrastructure and services, and reduce the likelihood of abrupt out-migration (a whole other messy ordeal we discuss in the article).

You can read our article here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44284-025-00365-0

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Cities

This journal aims to deepen and integrate basic and applied understanding of the character and dynamics of cities, including their roles, impacts and influences — past, present and future.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in