Climate hiccups and fisheries management headaches

Published in Earth & Environment and Ecology & Evolution

Commercially exploited for nearly 500 years, the iconic Northern Cod fishery was once the largest in the world. The stock collapsed in the early 1990s, forcing the government to impose a fishing moratorium in 1992. In the sole province of Newfoundland and Labrador, about 30,000 people – 12% of the workforce – lost their job overnight.

While fingers were pointed at the mismanagement of the stock, the collapse occurred during an unprecedented cold period in the northwest Atlantic. The cod collapse also coincided with the collapse of capelin and other groundfish stocks, including some that were not subjected to directed commercial fishing, further supporting the idea that environmental conditions may have played a key detrimental role on the ecosystem at the time.

Early signs of environmental control

As its name suggests, the Northern Cod stock is located in the coldest part of the species geographical distribution. The Newfoundland and Labrador shelf, where the stock is located, is also under the direct influence of Arctic currents. It is expected that any burst of colder than normal water may have a negative impact on the species, especially for the young cods.

Historical catches of Atlantic Cod peaked in the late 1960s with more than 800,000 tonnes reported caught. While those extraction levels far exceeded the capacity of the stock to sustain itself, they also occurred after a period of stable and warm climate uniquely favorable for the groundfish productivity. A situation that might have delayed the response of the stock to overfishing.

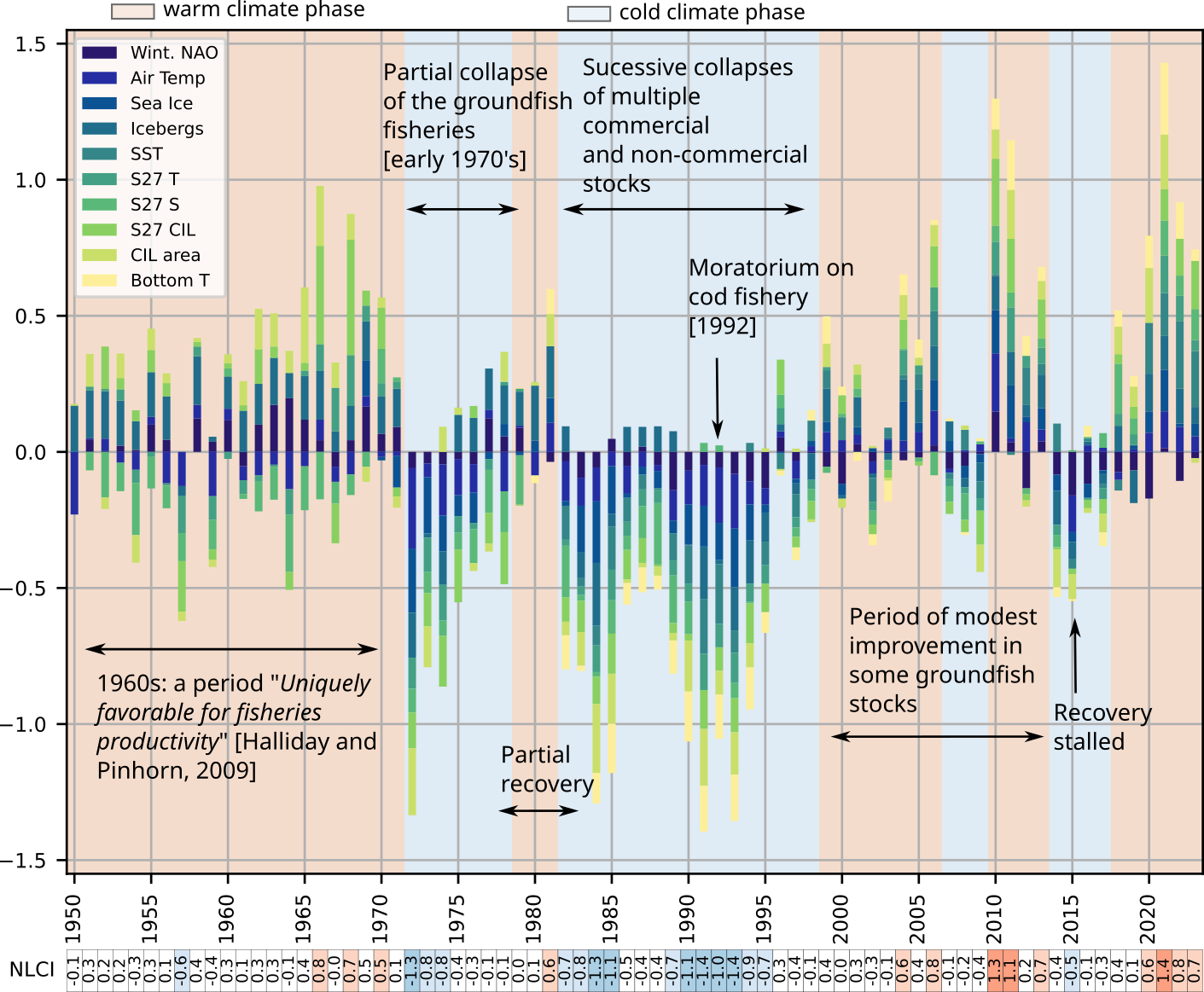

Things however changed rapidly. In the early 1970s, a first partial collapse of the Northern Cod stock coincided with a swift change in the climate. For example, 1972 was the second coldest year recorded since proper ocean monitoring begun after World War II. The coldest year was 1991, the year leading to the moratorium.

Ocean Climate and Fisheries

The northwest Atlantic Ocean is subject to large natural fluctuations of its climate, with known impacts on lower trophic levels and species distribution. However, as surprising as it may seem with hindsight, the causal relationship between changes in the ocean climate and fisheries was not clearly demonstrated until now. In a recent study published in Nature Communication, a group of Canadian researchers and I demonstrated that fisheries productivity is cyclical and in-sync with climate fluctuations.

Using 75 years of data, we showed that the northwest Atlantic climate can be separated into phases – lasting anywhere between 3 to 20 years – related to long-lasting atmospheric pressure anomalies in the northern hemisphere. These phases, which can be loosely classified as cold or warm, affect not only the productivity of cod and other commercial groundfish species, but also capelin, a key forage species, and other commercial and non-commercial species. Cold and warm phases also affect primary and secondary productions at the base of the food chain.

Overall, cold phases, such as the early 1970s or 1990s, are associated with reduced productivity, while warm phases seem to be associated with improved productivity and fisheries yields. One exception to this rule: cold-water shellfish species, such as snow crab and shrimp, better thrive in colder and weakly productive environments. Our study explains observed ecosystem shifts, such as the conversion to a shellfish-dominated ecosystem in the cold 1990s and the current return to a groundfish-dominated ecosystem as the climate becomes warmer.

Lack of recovery?

The elephant in the room is however why after more than 30 years of moratorium and a warming climate, the northern cod stock has not rebounded to historical levels? Our study also offers some clues. It confirms that the modest post-collapse cod comeback corresponded to warm climate conditions that culminated in the early 2010s. The recovery then stalled in relation with a short (2014-2017) but intense cold period that resembled that of the early 1990s.

We also note that in addition to 2014-2017, another cold phase of lesser magnitude (2006-2009) interrupted the otherwise warm climate prevailing between the late 1990s and the mid-2010s. Since the late 1990s, the northwest Atlantic climate has exhibited alternating colder and warmer conditions over relatively short phases and has not returned to a stable warm climate phase like the one observed in the 1950s and 1960s. This means that the climatic conditions and the setup preceding the record catches of the 1960s have not been replicated over the past 50 years.

The fact that the highly productive 1950s and 1960s were climatic anomalies rather than the norm suggests that we may need to temper our expectations about the northern cod recovery.

Environmental changes, overfishing and fisheries management

Disentangling overfishing and natural fluctuations of fish populations is a challenge because they are intrinsically related. Favorable environmental conditions can allow for fishing levels that may not be otherwise sustainable. That might have been the case in the 1960s.

In contrast, high fishing pressure can exacerbate the impacts of poor environmental conditions and accelerate the decline of fish stocks. A stock historically fished sustainably may become over-fished if its productivity declines because of environmental changes.

Can fisheries management adapt to this moving target? Sustainable fisheries management requires an understanding of the links between environmental conditions and fish populations, especially in the context of climate change.

Identifying the phases in which ocean climate fluctuations and changes in ecosystem productivity coincide, such as those proposed in our study, could provide a powerful tool to help inform fisheries management. It allows, for example, to set stronger emphasis on conservation during low productivity phases, or more permissive socio-economic objectives when the climate cooperates.

And precedents exist. In the Barents Sea, the prevalence of warmer ocean conditions combined with precautionary fisheries management has contributed to the rebuilding of the Atlantic Cod stock to record levels.

The future

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the Northern Cod fishery reopened in 2024 after a 32-year hiatus. This decision was not based on a significant improvement of the stock, but on a reevaluation of the threshold affecting its sustainability. Fortunately, the reopening also coincides with an emerging warmer and potentially more productive climate phase since 2020.

The timing of the fishery reopening may thus seem right. But to avoid future fisheries management headaches it remains essential to keep an eye on the next climate hiccup.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in