Computational approaches to link environment and aging

Published in Earth & Environment, Mathematics, and Statistics

New Computational Frameworks to Understand How the Environment Shapes Aging

For decades, scientists have sought to understand how large-scale environmental forces—such as pollution, structural inequality, and political instability—shape human health over time. Yet these efforts have been limited by a persistent gap: the lack of conceptual and methodological tools robust to capture the complexity of these macro-level phenomena and their impact on aging.

Much of the research has focused on isolated factors, relying on over simplistic models that fail to reflect the simultaneous and interacting exposures people face in real-world contexts. Often overlooked is the fact that aging is not merely a biological process—it is deeply embedded in the social, material, and political conditions in which we live.

A new generation of computational approaches is transforming this landscape. From exposome-wide models and artificial intelligence to multi-omics integration, biological aging prediction, factors associated with healthy aging, the analysis of environmental-genetic interactions, and network analysis, these tools enable researchers to link complex environmental exposures with individual aging trajectories. This shift represents a critical opportunity to develop more ecological, context-sensitive, and policy-relevant models.

Following thousands of lives around the world to model aging

In a recent study, we used cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses to map aging globally. The cross-sectional analysis included 161,981 healthy adults from 40 countries—Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe, Asia (China, South Korea, Israel, India) and Africa (Egypt). The longitudinal analysis then followed 21,631 participants across Latin America, Europe, and Asia, along with an independent South African cohort of 5,431 individuals, to observe how aging trajectories unfold over time.

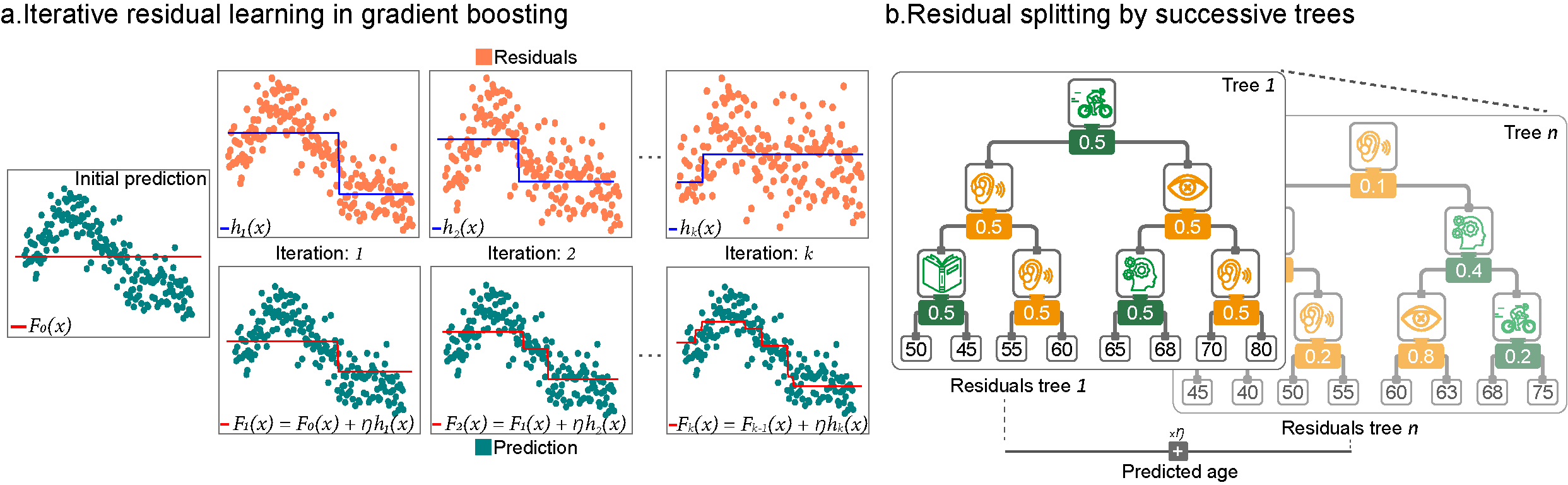

We trained an artificial intelligence model (gradient-boosting regressor) using 90% of the sample to predict people's age based on health and lifestyle factors, including both protective and risk-related ones. Then, we tested how well the model worked using the remaining 10% of the data, with a method called cross-validation. The model works by creating a series of decision trees, where each one learns from the mistakes of the previous one, resulting in progressively more accurate age estimates (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gradient boosting builds a strong predictive model by iteratively fitting small decision trees to the remaining errors. a) Starting with a constant prediction F0(x) (red line), each iteration computes residuals rk=y-Fk-1(x) (orange) and trains a simple tree hk(x) (blue) to predict them. The updated model Fk(x)=Fk-1(x)+hk(x) (red) gradually improves by adding a scaled correction (h: learning rate). b) Each residual tree splits according to the most relevant features, assigning corrections to leaves. Scaling these corrections ensures that only part of the residual is addressed each time. Subsequent trees refine what remains, producing a high-accuracy ensemble.

We used several measures to evaluate how well the model worked, but for simplicity,this blog highlights only two: R² and RMSE. R² quantifies the proportion of age variance the model explains, while RMSE tells us how far off the model's predictions are, on average, in years. In the full sample, R² was 0.26 (model explains 26%) and RMSE was 8.47. It performed better in the delayed‑aging subgroup (R² = 0.57 and RMSE = 6.51 years); and even better in the accelerated-aging group (R² = 0.69 and RMSE = 5.44).

Bridging predicted and chronological age to reveal BBAGs

We first calculated Biobehavioral age gaps (BBAGs) by subtracting each person’s actual age from the age predicted by our model. A BBAG greater than zero means faster-than-average aging. To remove the tendency of these raw gaps to drift with increasing age (a regression-to-the-mean artifact), we regressed raw BBAGs on chronological age, yielding an intercept α and slope β. The corrected BBAG is then the residual (with regression coefficients derived from the training data and applied to the test data) from this fit:

Corrected BBAGs showed delayed aging in Europe, followed by Asia and Latin America, with Africa exhibiting the greatest accelerated aging. Low-income countries experienced more accelerated aging than high-income countries (δd = 0.48 by GNI, δd = 0.56 by GDP). Adverse exposomal conditions, including poor air quality, structural and gender inequality, migration pressures, weak political representation and limited democratic freedoms, were all strongly associated with accelerated BBAGs across countries, highlighting how macro-level environments drive aging disparities.

Corrected BBAGs showed delayed aging in Europe, followed by Asia and Latin America, with Africa exhibiting the greatest accelerated aging. Low-income countries experienced more accelerated aging than high-income countries (δd = 0.48 by GNI, δd = 0.56 by GDP). Adverse exposomal conditions, including poor air quality, structural and gender inequality, migration pressures, weak political representation and limited democratic freedoms, were all strongly associated with accelerated BBAGs across countries, highlighting how macro-level environments drive aging disparities.

Translating accelerated aging into epidemiological risk profiles

To study how accelerated aging affects health, we classified BBAGs into two groups: values above zero (accelerated aging) and values at or below zero. We then used this yes/no measure as the main factor in our epidemiological models. For cross-sectional outcomes (cognition and functional ability), we fitted logistic regression models of the form:

from which odds ratios were computed as eB1 and attributable risks as the difference in event probabilities between exposed and unexposed groups.

For longitudinal outcomes (changes in well-being, cognition, and functionality in daily life over time), we calculated relative risk (RR), the ratio of outcome probabilities in accelerated versus non-accelerated agers, and attributable risk (AR), the absolute difference between those probabilities (Riskexposed-Riskunexposed).

Country-level ORs and RRs were then pooled via common- and random-effects meta-analyses (REML, I²). This framework ensured robust, comparable estimates of how accelerated biobehavioral aging translates into real-world declines in cognition and function across diverse settings.

In cross-sectional analyses, accelerated agers had an odds ratio of 7.64 for functional decline (attributable risk ≈ 27.2 %) and an odds ratio of 4.41 for cognitive impairment (attributable risk ≈ 14.8 %). In longitudinal follow-up, accelerated BBAGs were associated with a relative risk of 1.40 for functional decline, 1.25 for cognitive decline, and 1.16 for well-being decline. When results from all countries were combined, the meta-analysis showed that accelerated BBAGs roughly doubled the odds of functional and cognitive impairment and increased long-term risks by two- to threefold, with consistent effects across both high- and low-income settings, despite moderate variation between studies.

Moving from Fragmented Models to Integrated Environmental Aging Science

We may move beyond the reductionist view that aging is shaped mainly by individual behaviors or isolated biological factors. Aging is dynamically embedded within the broader ecological systems we inhabit. These are systems marked by pollution, inequality, social unrest, and political instability. These macro-level forces structure the pace and quality of how we age.

Our ability to understand and act on these forces has long been limited by methodological gaps. However, new computational tools now allow us to trace the imprint of the environment on biological aging with unprecedented precision. This marks a shift from fragmented models to integrative approaches that account for the complexity of real-world exposures.

The poster figure was created by ChatGPT with oversight from the authors.

Figure 1 was created by the authors using Python and Inkscape.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Medicine

This journal encompasses original research ranging from new concepts in human biology and disease pathogenesis to new therapeutic modalities and drug development, to all phases of clinical work, as well as innovative technologies aimed at improving human health.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Stem cell-derived therapies

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 26, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in