Forecasting the Unforeseen: How a "Black Box" Failure Revealed the Inequality Crisis in Global Water Security

Published in Social Sciences, Earth & Environment, and Statistics

The "Black Box" Dilemma: A False Start

The research landscape of global water scarcity has long been dominated by process-based integrated assessment models (like GCAM). While powerful, these models rely heavily on rigid assumptions about human behavior and often fail to capture complex, non-linear adaptive responses. This limitation sparked our curiosity in 2022: Could machine learning see patterns that traditional models missed?

Our journey began with high hopes but hit a crushing reality check. Our initial attempt produced startling forecasts—predicting much higher levels of scarcity than existing literature. We submitted our findings to Nature Geoscience in October 2023. We waited months with bated breath, only to receive a rejection letter in February 2024. It was a difficult moment for our team. The email felt like a bucket of ice water. We had spent months refining the code, convinced that our advanced neural networks were telling us something profound. Yet, the reviewers were unimpressed by our "magic numbers." They rightly criticized our approach as a "black box." We had generated alarming forecasts, but we couldn’t explain why the model was making them. We realized we had fallen into a common trap in modern science: "package-surfing"—applying complex algorithms without sufficient grounding in hydrological and socioeconomic reality. We were predicting the "what," but we were blind to the "why."

The rejection was a turning point in more ways than one. Our initial research team had been larger, but in the wake of the disappointment, members drifted apart. Only the three of us remained, united by a stubborn belief that our core idea—using data to challenge traditional models—still had immense value. We looked at each other and decided not just to "fix" the paper, but to completely reimagine it. This wasn't just a revision; it was the birth of an entirely new study.

The Eureka Moment: From Prediction to Interpretation

Stung by the rejection but determined to find the truth, we went back to the drawing board for 18 grueling months. This was a period of intense soul-searching for the project. We debated whether to abandon the machine learning approach entirely or to double down and fix its flaws. Ultimately, we chose the harder path: not just rebuilding the model, but fundamentally changing how we interacted with it. We realized that to make a real contribution, we couldn't just predict the future; we had to understand the human mechanisms driving it.

We pivoted from standard predictive modeling to Interpretable Machine Learning. Instead of treating the algorithm as a magic oracle, we used diagnostics (like SHAP values) to peel back the layers of the model. Think of standard machine learning as a telescope that shows you a distant star but tells you nothing about what it's made of. Interpretable ML, by contrast, is like a prism that splits the star's light into a spectrum, revealing its chemical composition. By applying this "prism" to our model, we could finally see exactly which factors—GDP, population growth, technological adoption, or governance quality—were driving water use in every single region and for every projected year.

This was our turning point. As we decoded the model's logic, a critical, previously overlooked dynamic emerged from the data like a hidden signal in the noise: Inequality.

The Efficiency-Equity Trade-off

This discovery fundamentally changed our understanding. Our interpretable model exposed a persistent paradox: the "Efficiency-Equity Trade-off." Traditional narratives suggest that as nations develop and technology improves, water use becomes more efficient, eventually alleviating scarcity. However, our data showed a more complex reality.

In high-emission, technology-driven scenarios (like SSP5), we saw that the consumption demands of affluent populations simply outpace technological gains. It is a classic "rebound effect" playing out on a planetary scale: as water use becomes more efficient, it becomes cheaper and more accessible to the wealthy, who then use even more of it for water-intensive lifestyles and industries. While wealthy regions become hyper-efficient, the gap widens. Our model revealed that this structural inequality is not just a social issue; it is a primary driver of physical water scarcity for the developing world. By ignoring equity, we were missing half the picture. We realized that fairness isn't just a moral goal; it's a hydrological necessity.

Pushing the Limits: A Sobering Projection

With our new methodology, which combined the predictive power of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with the interpretability of SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), we re-evaluated global scenarios.

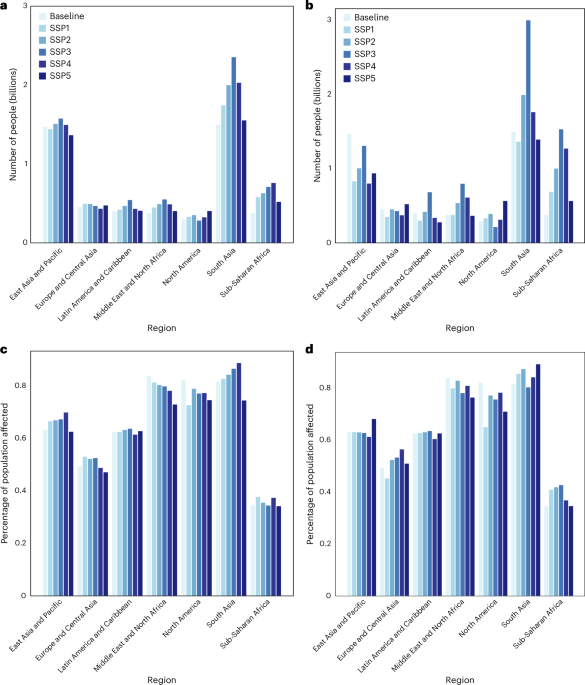

Fig. 1. Projections of global water scarcity in 2100. Our model indicates that under high-inequality pathways, water stress intensifies significantly across the Global South, affecting billions more people than previously estimated.

The results were stark. Our model projects that by 2050, roughly 6.5 billion people could face severe water scarcity. By 2100, under a fossil-fueled development scenario, this figure could rise to nearly 8 billion—approximately 63% to 80% of the global population. These figures significantly eclipse previous estimates derived from traditional models. We found that social fragmentation is not just a political issue; it is a physical threat to water security, as dangerous as climate change itself.

Sustainability and Broader Impact

Beyond the numbers, this research fundamentally shifts the narrative around water security. It provides a quantitative basis for the argument that we cannot "engineer" our way out of the water crisis with better pipes and dams alone.

For policymakers, our findings are a wake-up call: relying solely on technological fixes is destined to fail. To secure our future water supply, we must confront the uncomfortable reality of structural inequality. The solution is not just hydrological; it is deeply political and social. We need governance frameworks that prioritize access for the vulnerable over efficiency for the elite.

Looking forward, our work opens new avenues for research. We hope to inspire a shift away from "black box" machine learning toward transparent, interpretable models that can uncover the human dimensions of environmental change. Future studies must integrate local-scale granularity and groundwater dynamics to fully map the water crisis. Ultimately, we hope this story encourages other researchers to view rejection not as a failure, but as a necessary step toward a deeper, more meaningful discovery. Sometimes, you have to break the box to see what's inside.

More details of this study can be found in our recent article "Global water security threatened by rising inequality" published in Nature Geoscience.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Geoscience

A monthly multi-disciplinary journal aimed at bringing together top-quality research across the entire spectrum of the Earth Sciences along with relevant work in related areas.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Past sea level and ice sheet change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Lithium and copper resources for net zero

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in