Four-Scene Circumstances: A Tale of Visual Complexity and Origin

Published in Neuroscience

A central goal of research in developmental neurobiology is to understand how this diversity of neuron types is generated. Neuronal stem cells are unique cells that act as shapeshifters, possessing the ability to each generate multiple neuronal types. They serve as the building blocks that facilitate the proper construction of a functional brain.

Several model organisms have been used to investigate neuronal stem cells, but the Drosophila fruit fly has emerged as a prime model and one of the most extensively studied. Over the past century, countless discoveries using Drosophila have deepened our understanding of various biological disciplines, including genetics, development, neuroscience, and disease. More specifically, Drosophila has one of the best-characterized systems of neural stem cells1. Different types of neuronal stem cells and their modes of division have been extensively investigated in the fly’s nervous system, encompassing the nerve cord, central brain, and visual optic lobes2.

The large diversity of neurons in the Drosophila brain is the result of several mechanisms, including temporal and spatial patterning. A temporal transcription cascade was discovered in the fly ventral nerve cord, followed by the identification of several other temporal cascades in the optic lobes3-7. During temporal patterning, neural stem cells express a series of different temporal transcription factors (tTFs) as they age, generating distinct neuronal populations at each stage. Additionally, different spatial transcription factors (sTFs) are expressed in various locations within the brain, influencing the diversity of neurons produced by the temporal cascade8-13. As a result, neurons produced in the same temporal window and expressing the same tTFs can acquire different identities depending on the location of the neural stem cells.

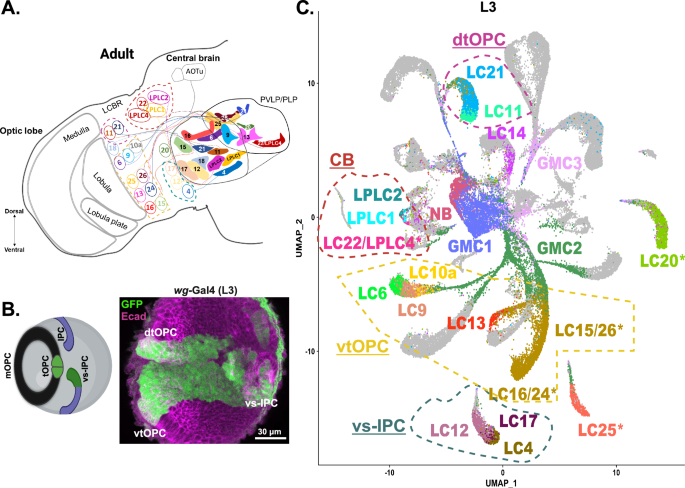

The Drosophila optic lobe comprises several structures called neuropils, which integrate and analyze different visual features. These include the lamina, medulla, lobula, and lobula plate. Neurogenesis in the medulla and lobula plate has been extensively studied1,14-15. Neurons from these neuropils originate from two primary neuroepithelial domains: the outer proliferation center (OPC), and the inner proliferation center (IPC)16-18, which can be further divided into subdomains. In contrast, very little is known about the neurogenesis of the lobula, which contains visual projection neurons that serve as a crucial link between vision and behavior. These neurons, called lobula columnar neurons (LCNs), comprise 20 subtypes and play essential roles in detecting various visual stimuli19-22, such as looming22-26 (threat detection from predators), figure-ground discrimination27, small dark moving object detection28-30, small moving object tracking31, and mate tracking during courtship32-33. Given their critical function in survival, understanding the generation of these neurons is essential, particularly because they exhibit similarities with mammalian retinal ganglion cells that also convey information from the eye to the brain.

This project was conducted at New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In recent years, the UAE has experienced rapid advancements in various domains, emerging as a hub for technological innovation, education, and progress in the Arab world and the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. However, neuroscience research remains in its early stages there. The COVID-19 pandemic posed significant challenges as laboratory access was restricted due to social distancing regulations. Additionally, obtaining fruit flies and reagents proved difficult, as local supplies were not available, with most requiring international shipping. We leveraged the opportunity to analyze existing datasets. Our lab had previously identified the entire set of mRNAs (transcriptome) in each of the optic lobe neurons across all developmental stages15. Using this dataset, we successfully assigned transcriptome identities to all LCNs. This was the first step toward understanding the origins of these neurons.

Our lab discovered that a specific type of LCN, known as LC6, originates from a domain of the OPC called the tips of the OPC (tOPC), which expresses Wingless34. We identified a line expressed in Wingless+ cells whose expression was localized to the tOPC and ventral surface IPC (vs-IPC). With this knowledge of the transcriptomic identity of all LCNs, we traced the origins of LCNs to four distinct neural stem cell domains: the ventral and dorsal tOPC, vs-IPC, and the dorsal central brain35. Next, we mined a database of fly lines that show expression in different LCN types, guided by the gene expression profiles of these neurons. This approach assigned the developmental origins of these neurons by mapping their locations in the brain and verifying the expression of their specific genes.

This discovery was particularly intriguing, as it marked the first time that several subtypes of neurons were found to emerge from different progenitor pools with distinct division patterning and then converge to similar functions. This finding represents an important evolutionary mechanism, highlighting the critical role of studying vision in Drosophila. By recruiting different brain regions to construct parallel pathways independently, the species ensures the robustness of its visual processing system.

I would like to dedicate this paper to all women in science, especially mothers. I wrote this manuscript while pregnant and after giving birth to my child. To all the women who face challenges yet continue to contribute to the advancement of research and science—this work is for you.

References:

- Holguera, I. & Desplan, C. Neuronal specification in space and time. Science 362, 176-180 (2018). https://doi.org:10.1126/science.aas9435

- El-Danaf, R. N., Rajesh, R. & Desplan, C. Temporal regulation of neural diversity in Drosophila and vertebrates. Semin Cell Dev Biol 142, 13-22 (2023).

- Konstantinides, N. et al. A complete temporal transcription factor series in the fly visual system. Nature 604, 316-322 (2022). https://doi.org:10.1038/s41586-022-04564-w

- Li, X. et al. Temporal patterning of Drosophila medulla neuroblasts controls neural fates. Nature 498, 456-462 (2013). https://doi.org:10.1038/nature12319

- Sato, M., Yasugi, T. & Trush, O. Temporal patterning of neurogenesis and neural wiring in the fly visual system. Neurosci Res 138, 49-58 (2019). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.neures.2018.09.009

- Suzuki, T., Kaido, M., Takayama, R. & Sato, M. A temporal mechanism that produces neuronal diversity in the Drosophila visual center. Developmental Biology 380, 12-24 (2013). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.05.002

- Zhu, H., Zhao, S. D., Ray, A., Zhang, Y. & Li, X. A comprehensive temporal patterning gene network in Drosophila medulla neuroblasts revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun 13, 1247 (2022). https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-022-28915-3

- Dearbon, R. & Kunes, S. An axon scaffold induced by retinal axons directs glia to destinations in the Drosophila optic lobe. Development 131, 2291-2303 (2004). https://doi.org:10.1242/dev.01111

- Erclik, T. et al. Integration of temporal and spatial patterning generates neural diversity. Nature 541, 365-370 (2017). https://doi.org:10.1038/nature20794

- Gold, K. S. & Brand, A. H. Optix defines a neuroepithelial compartment in the optic lobe of the Drosophila brain. Neural Dev 9, 18 (2014). https://doi.org:10.1186/1749-8104-9-18

- Islam, I. M., Ng, J., Valentino, P. & Erclik, T. Identification of enhancers that drive the spatially restricted expression of vsx1 and rx in the outer proliferation center of the developing drosophila optic lobe. Genome 64, 109-117 (2021). https://doi.org:10.1139/gen-2020-0034

- Perez, S. E. & Steller, H. Migration of glial cells into retinal axon target field in Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurobiol 30, 359-373 (1996). https://doi.org:10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199607)30:3<359::Aid-neu5>3.0.Co;2-3

- Malin, J. A., Chen, Y. C., Simon, F., Keefer, E. & Desplan, C. Spatial patterning controls neuron numbers in the Drosophila visual system. Dev Cell 59, 1132-1145.e1136 (2024)

- Doe, C. Q. Temporal Patterning in the Drosophila CNS. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 12, 55-55 (2017). https://doi.org:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315

- Özel, M. N. et al. Neuronal diversity and convergence in a visual system developmental atlas. Nature 589, 88-95 (2021). https://doi.org:10.1038/s41586-020-2879-3

- Apitz, H. & Salecker, I. A region-specific neurogenesis mode requires migratory progenitors in the Drosophila visual system. Nature Neuroscience 18, 46-55 (2015). https://doi.org:10.1038/nn.3896

- Oliva, C. et al. Proper connectivity of Drosophila motion detector neurons requires Atonal function in progenitor cells. Neural Dev 9, 4 (2014). https://doi.org:10.1186/1749-8104-9-4

- Pinto-Teixeira, F. et al. Development of Concurrent Retinotopic Maps in the Fly Motion Detection Circuit. Cell 173, 485-498.e411 (2018). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.053

- Fischbach, K. F. & Dittrich, A. P. M. The optic lobe of Drosophila melanogaster. I. A Golgi analysis of wild-type structure. Cell and Tissue Research 258, 441-475 (1989). https://doi.org:10.1007/BF00218858

- Otsuna, H. & Ito, K. Systematic analysis of the visual projection neurons of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Lobula-specific pathways. Journal of Comparative Neurology 497, 928-958 (2006). https://doi.org:10.1002/cne.21015

- Panser, K. et al. Automatic Segmentation of Drosophila Neural Compartments Using GAL4 Expression Data Reveals Novel Visual Pathways. Biol. 26, 1943-1954 (2016). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.052

- Wu, M. et al. Visual projection neurons in the Drosophila lobula link feature detection to distinct behavioral programs. eLife 5, e21022 (2016). https://doi.org:10.7554/eLife.21022

- Ache, J. M. et al. Neural Basis for Looming Size and Velocity Encoding in the Drosophila Giant Fiber Escape Pathway. Biol. 29, 1073-1081.e1074 (2019).

- Klapoetke, N. C. et al. Ultra-selective looming detection from radial motion opponency. Nature 551, 237-241 (2017). https://doi.org:10.1038/nature24626

- Sen, R. et al. Moonwalker Descending Neurons Mediate Visually Evoked Retreat in Drosophila. Biol. 27, 766-771 (2017). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.008

- von Reyn, C. R. et al. Feature Integration Drives Probabilistic Behavior in the Drosophila Escape Response. Neuron 94, 1190-1204.e1196 (2017). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.036

- Aptekar, J. W., Keleş, M. F., Lu, P. M., Zolotova, N. M. & Frye, M. A. Neurons forming optic glomeruli compute figure–ground discriminations in Drosophila. Journal of Neuroscience 35, 7587-7599 (2015). https://doi.org:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0652-15.2015

- Keleş, M. F., Hardcastle, B. J., Städele, C., Xiao, Q. & Frye, M. A. Inhibitory Interactions and Columnar Inputs to an Object Motion Detector in Drosophila. Cell Reports 30, 2115-2124.e2115 (2020). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.061

- Keleş, M. F. & Frye, M. A. Object-Detecting Neurons in Drosophila. Biol. 27, 680-687 (2017). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.012

- Tanaka, R. & Clark, D. A. Object-Displacement-Sensitive Visual Neurons Drive Freezing in Drosophila. Biol. 30, 2532-2550.e2538 (2020). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cub.2020.04.068

- Klapoetke, N. C. et al. A functionally ordered visual feature map in the Drosophila brain. Neuron 110, 1700-1711.e1706 (2022). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.neuron.2022.02.013

- Ribeiro, I. M. A. et al. Visual Projection Neurons Mediating Directed Courtship in Drosophila. Cell 174, 607-621.e618 (2018). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.020

- Sten, T. H., Li, R., Otopalik, A. & Ruta, V. Sexual arousal gates visual processing during Drosophila courtship. Nature 595, 549-553 (2021). https://doi.org:10.1038/s41586-021-03714-w

- Bertet, C. et al. Temporal patterning of neuroblasts controls notch-mediated cell survival through regulation of hid or reaper. Cell 158, 1173-1186 (2014). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.045

- El-Danaf, R.N. et al. Morphological and functional convergence of visual projection neurons from diverse neurogenic origins in Drosophila. Nature Communications 16(1):698. (2025). doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-56059-7

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in