From rock to reveal: How we unlock ancient air in fossil cosmic dust

Published in Earth & Environment

Motivation

Studying the evolution of our solar system from a geological perspective has always fascinated me. Meteorites serve as messengers carrying sometimes exotic chemical and isotopic signatures that allow us to explore processes on an interplanetary scale. Micrometeorites compress this research into particles the size of dust grains, and they furthermore contain valuable records of our own planet’s history. Most importantly, they preserve the oxygen isotope composition of Earth’s atmosphere, enabling reconstructions of CO2 levels and global primary productivity.

This compelling potential fueled my curiosity when I began my doctoral project in 2021, focused on analyzing fossil iron-type micrometeorites for their triple oxygen and iron isotope compositions—an endeavor that required two key developments.

First, we had to adapt established methods for measuring triple oxygen isotopes in silicate and oxide minerals to work on samples roughly one-thousandth the mass of the conventional sample mass (~2 milligrams). Extracted micrometeorites typically weigh less than a few micrograms, making high-precision analysis challenging.

Second, we needed to identify suitable sedimentary host rocks from across the Phanerozoic eon—rocks that had the best chance of preserving fossil micrometeorites despite millions of years of burial history. Once located, these precious samples demanded meticulous and efficient preparation techniques to extract them from tens of kilograms of rock.

Method development and challenges

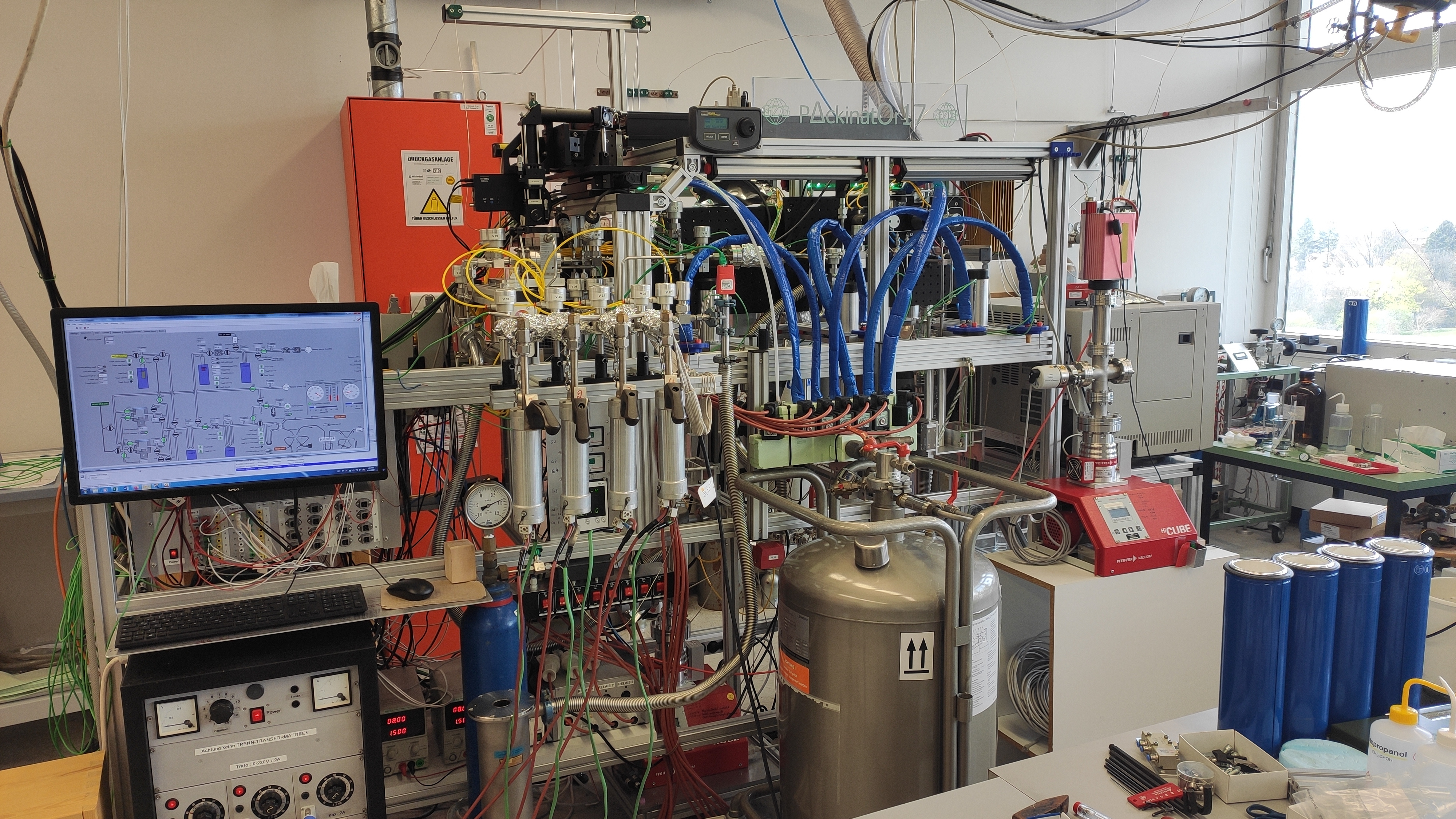

Our major challenge in oxygen isotope analysis was to reduce the background oxygen contamination of the laser fluorination system at the University of Göttingen to reliably measure the extremely small oxygen volumes released by micrometeorites—down to the nanomole scale compared to the typical tens of micromoles for conventional samples.

Fortunately, a new laser fluorination line in the Stable Isotope lab of the Geoscience Department in Göttingen was commissioned just in time. It featured major hardware improvements such as welded connections minimizing leaks, and a carefully designed system built upon years of experience with the previous setup.

Refined protocols for vacuum conditioning, cleaning, and laser operations were developed to ensure clean oxygen extraction and purification. We also optimized gas flow rates and signal detection on the mass spectrometer to maximize precision at the lowest oxygen volumes.

This setup allowed us to successfully analyze modern urban rooftop micrometeorites as a proof of concept, demonstrating that precise triple oxygen isotope measurements were achievable even at such minuscule sample sizes (see Zahnow et al., 2023 - https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.14084).

Since fossil micrometeorites were often smaller still, we further devised a method to analyze their iron isotope composition from the iron fluoride residue remaining after oxygen extraction. Collaborating closely with the University of Hannover’s Mineralogy Department, we confirmed that analyzing these residues required minimal sample mass while maintaining the necessary precision.

This approach—analyzing both oxygen and iron isotopes from the same tiny sample—was critical for maximizing data yield, especially given the limited availability of fossil micrometeorite material.

Searching for the extraterrestrial needle in the haystack

With analytical methods in place, we turned to locating micrometeorite-rich sedimentary rocks. Our goal was to assemble representative collections spanning different geologic periods characterized by varying paleo-atmospheric CO2 levels.

We extensively researched regional geological literature for reports of ‘unidentified dark spherules’—potential micrometeorites—and contacted institutions curating relevant rock samples.

Our field expeditions took us to unique sites in Germany such as deep salt mines in Braunschweig and Merkers (approximately 800 m underground) and the extensive repositories of the Bavarian Environmental Agency in Hof.

We assembled and modified equipment—including crushers, sieves, and magnetic separators—using a combination of standard laboratory tools and locally sourced hardware store materials, such as equipment for a salt shower and permanent magnets.

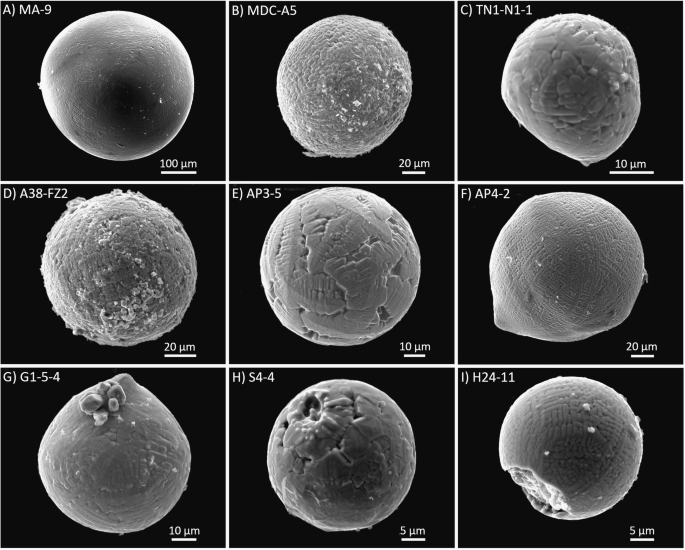

Over the course of processing about 100 kilograms of rock, we recovered roughly 100 micrometeorites with a total mass of approximately 160 micrograms (or 1.6 x 10-7 kilograms)—a testament to the challenge of finding these tiny extraterrestrial particles.

Implications for future research

Our work highlights that fossil micrometeorite research requires large-scale processing or targeting of lithologies that effectively preserve these particles. In the paper we suggest carbonate rocks may offer favorable preservation conditions and warrant further focused investigation.

Achieving high-precision triple oxygen and iron isotope analysis on these minute particles remains a demanding analytical challenge, necessitating continuous advancements in instrumentation and methodology.

Significantly, we demonstrated that paleo-atmospheric CO2 concentrations can be inferred with competitive precision from single, intact fossil micrometeorites. Future studies should aim to recover larger numbers of well-preserved particles from single time intervals and locations to improve the robustness of paleoenvironmental reconstructions.

If you are interested in what fossil micrometeorites reveal about the oxygen isotope composition of ancient air and their implications for past CO2 levels, we invite you to read our full publication in Communications Earth & Environment (Zahnow et al., 2025 - https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02541-5).

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in