Greater adverse consequences of weight gain in South Asian compared with white European men. Findings from the GlasVEGAS study

Published in Biomedical Research, General & Internal Medicine, and Anatomy & Physiology

High risk of type 2 diabetes in South Asians even at low BMIs

People of South Asian ethnicity – who comprise about a quarter of the world’s population – have a 3-5 fold higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes compared to people of white European ancestry, a steeper increment in diabetes risk per unit increase in body mass index (BMI), and develop the disease about a decade earlier in life. For a given BMI, South Asians have a higher percentage body fat, more liver fat, larger subcutaneous abdominal adipocytes and lower muscle mass compared with white Europeans – factors which are all associated with metabolic dysfunction and type 2 diabetes risk. This suggests that ethnic differences in body composition, particularly the capacity to store fat in ‘safe’ subcutaneous depots, and/or in adipocyte morphology, may contribute to South Asians’ greater metabolic risk.

Could ethnic differences in metabolic responses to weight gain contribute?

A limitation of the existing literature was that the evidence was largely cross-sectional: it is known that South Asians with higher BMIs exhibit greater metabolic dysfunction than white Europeans with similarly high BMIs, but not whether the metabolic consequences of weight gain within an individual differ between people of South Asian compared with white European ethnicity. To address this, the Glasgow visceral and ectopic fat with weight gain in South Asians (GlasVEGAS) study recruited 14 South Asian and 21 white European men in their early 20s, with starting BMIs of ~22 kg.m-2, and asked them to undertake an overfeeding intervention to gain 5-7% of their bodyweight over 4-6 weeks. We assessed their metabolic responses to consuming a mixed meal, measured their body composition by magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy, and took abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies at baseline (i.e. before weight gain) and after weight gain.

Ethnic differences at baseline in GlasVEGAS

At baseline, the South Asian men in our study had more whole-body, upper-body, lower-body and abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue than the white European men. They also had more liver fat and less whole-body lean tissue. South Asians had substantially larger adipocytes at baseline, with mean adipocyte diameter being 18% larger and adipocyte volume being 76% larger, than in white Europeans. They also had a larger proportion of large adipocytes (26.2% vs 9.1%) and smaller proportion of small adipocytes (37.1% vs 60.0%). Their insulin response to consuming a mixed meal was 62% higher than white Europeans and their triglyceride response was 48% higher at baseline. However, there was no statistically significant difference at baseline between ethnic groups in insulin sensitivity, as assessed by the Matsuda Insulin Sensitivity Index. These findings were consistent with previous cross-sectional research in the field.

Ethnic differences in responses to weight gain

Both ethnic groups gained the same amount of weight in response to the intervention, about 4.5 kg or ~1.4 kg.m-2 BMI. However, although the increase weight, BMI, waist circumference and whole, upper- and lower-body adiposity in response to the weight-gain intervention did not differ between ethnic groups, the white European men experienced a more than three-fold larger increase in lean tissue in response to weight gain than the South Asians (2.4 vs 0.7 l). This greater anabolic response seen in the white Europeans may act to buffer against some of the adverse metabolic responses of weight gain since muscle is an important sink for clearing glucose from the bloodstream.

The weight-gain intervention led to substantially greater adverse metabolic responses in the South Asian men, who experienced a 38% decrease in insulin sensitivity, compared with just a 7% decrease in the white Europeans. The increase in postprandial insulin concentrations in response to weight gain was 4-fold higher in the South Asians.

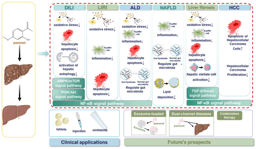

We found considerable inter-individual variability in the changes in adipocyte size with weight-gain. However, there was a statistically significant ethnicity x weight-gain interaction for the changes in very small adipocytes, with white Europeans experiencing a greater decrease in this adipocyte pool with weight gain than South Asians. This implies that in the white Europeans greater lipogenesis occurred in these very small adipocytes in response to overfeeding, leading them to increase in size and become larger adipocytes. A summary of the main study findings is shown in the figure below:

.jpg)

Ethnic differences in adipocyte morphology associated with adverse metabolic changes

A key observation in this study was that both the size distribution of adipocytes at baseline, and the changes with weight gain, were associated with the extent of the metabolic changes in response to weight gain. Having a greater proportion of large adipocytes at baseline, a smaller proportion of small adipocytes at baseline, and a smaller decrease in the proportion very small adipocytes with weight gain – all of which were evident in South Asians – were all associated with a greater adverse metabolic response to weight gain. The figure below illustrates the association between the proportion of large adipocytes at baseline and the change in the postprandial insulin response with weight gain. This suggests that ethnic differences in adipocyte morphology may be an important driver of South Asian men’s augmented adverse metabolic response to weight gain.

%20no%20legend%20square.jpg)

Conclusions and Implications

In conclusion, the GlasVEGAS study demonstrated that modest weight gain led to substantially greater adverse metabolic consequences in South Asian compared with white European men. We found that while white European men appear to exhibit a degree of metabolic buffering capacity before weight gain leads to adverse metabolic consequences, this does not appear to be present to the same extent in South Asian men. Our data suggests that South Asian men having a greater proportion of hypertrophic adipocytes, and fewer small adipocytes, contributes to the effect, reinforcing the imperative for prevention of weight gain in this group.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Metabolism

This journal publishes work from across all fields of metabolism research that significantly advances our understanding of metabolic and homeostatic processes in a cellular or broader physiological context, from fundamental cell biology to basic biomedical and translational research.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in