Harnessing the Epithelial Epigenome: A New Frontier in Breast Cancer Prevention

Published in Cancer and Biomedical Research

Breast cancer remains by far the most common cancer among women under 40 - and the leading cause of cancer-related death in this group. While inherited mutations do play a role - about 10% of these cases are caused by BRCA1gene mutations – most cases are not clearly attributed to genetics. This raises several urgent questions: what drives the majority of breast cancers in young women, and how can we better predict, prevent, and monitor the risk for this devastating disease?

Our recent body of work, published in three new studies which appeared on April 2, 20251-3 (Figure 1), explores the potential of the epigenome (specifically DNA methylation) for personalized, non-invasive cancer prevention. The epigenome is superimposed upon the genetic sequences and shapes cell differentiation and function. While dysregulation of the epigenome is strongly linked to cancer, it also allows cells to adapt dynamically to exposures, resulting in lasting epigenetic “footprints” or “memories”. These “footprints” may have the potential to tell us about past, present, and future, in other words what a cell or person has experienced in the past, its current status, and potential future risk of disease.

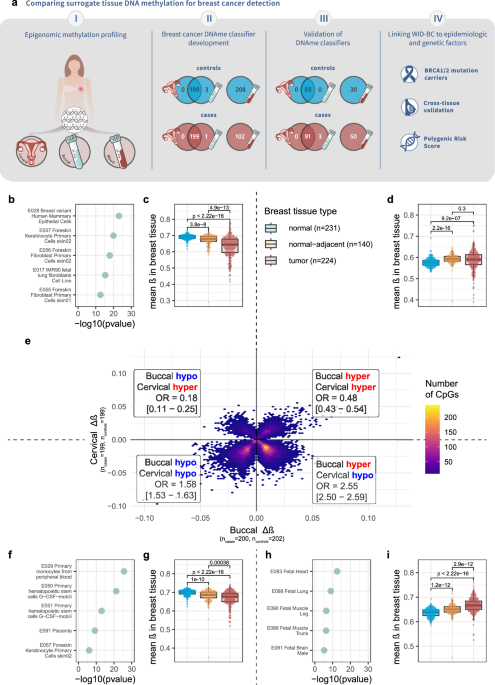

In our recent study, we therefore explored the capacity of DNA methylation footprints in multiple tissues across the body, including sources of immune and epithelial cells [tissues such as the cervix and buccal (cheek) cells] to reflect exposures that may be linked to cancer development, and cancer risk.

The Role of Progesterone in Poor-Prognostic Breast Cancer Development

While inherited mutations like BRCA1 increase breast cancer risk, our work previously demonstrated that women who develop breast cancer at a young age often exhibit elevated progesterone levels during the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle 4,5. In breast tissue, progesterone activates the release of RANKL, a molecule that promotes the expansion and cell division of so-called luminal progenitor cells 6,7. The expansion of luminal progenitor cells is a precursor to triple-negative breast cancer 8, the most aggressive breast cancer subtype with the poorest prognosis.

Progesterone’s role is not only evident in the endogenous hormone cycle. Exogenous progesterone - such as that found in hormone replacement therapy - has also been linked to increased risk of aggressive breast cancers 9. Taken together, these findings suggest that lifelong exposure to progesterone is a critical, modifiable risk factor. Intriguingly, our previous research demonstrated that we can monitor the expansion of these luminal progenitors via DNA methylation signatures 10.

Antagonising Progesterone with Mifepristone: a Targeted Prevention Strategy

Understanding the mechanisms underlying (pre)cancer formation – for instance through the expansion of luminal progenitor cells described above – uncovers new possibilities for targeted prevention. Our prior work showed that mifepristone, a progesterone antagonist, reduces both the proportion of luminal progenitor cells and the replicative (=mitotic) age of breast epithelial tissue - two hallmarks of increased breast cancer risk 10. However, the previous work leveraged breast biopsies before and after two months of treatment without a cancer endpoint, as it included only cancer-free individuals. We therefore lacked a comprehensive understanding of mifepristone’s effect on cancer incidence. Moreover, this work relied on breast biopsies, which would be unsuitable to apply in routine preventive settings: therefore, we wanted to explore whether the epigenomes in other tissues could reflect what is happening in the breast tissue. Our approach thereby takes prevention beyond identifying risk and adds personalized strategies to reduce risk.

This work provides the first evidence that DNA methylation signatures, when measured in surrogate epithelial tissues, can reflect both cancer risk and the effectiveness of preventive interventions.

The Importance of Tissue Type in Epigenetic Risk Assessment

To test the relevance of these findings in humans, we directly compared DNA methylation patterns in blood, cervical, and buccal samples from women with and without breast cancer. The results were striking: while DNA methylation in blood samples, primarily derived from immune cells, failed to meaningfully distinguish between cases and controls, epithelial samples from the cervix and cheek performed significantly better.

Not only could these non-invasive epithelial samples differentiate women with breast cancer from healthy controls, but the epigenetic signatures they carried also mirrored patterns found in actual breast tissue. This is despite the fact that buccal samples are unlikely to contain any tumor DNA that would have contributed these similar patterns. Thebuccal-derived signature distinguished between cancer tissue and normal breast with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of ~0.9. Intriguingly, our analyses consistently showed that the directionality of buccal differential methylation between cancer cases and control matched that of breast tissue, whereas cervical samples showed an inverse association. Nonetheless, both tissues were able to distinguish between cases and controls.

Rethinking Epigenetic Ageing in Cancer

Published in Communications Medicine3, this work not only improves our understanding of cancer biology but also reinforces the potential of the epigenome to serve as a window into future disease risk - if we interpret it correctly.

Looking Ahead: Toward an Epigenome-Guided Prevention Pathway

Our next steps are clear. We must validate these signatures in large, population-based cohorts, ideally with samples collected years before diagnosis. We must also test - initially in women at highest risk, such as BRCA1 mutation carriers - whether preventive interventions like mifepristone can be guided and monitored using epigenetic signatures.

If successful, this approach could lay the groundwork for a new era of truly personalized cancer prevention - one that’s proactive, precise, and non-invasive. While we are still at the beginning of this journey, the future for harnessing the epigenome for individualized risk prediction and prevention is looking bright.

1. Barrett JE, Herzog CM, Aminzadeh-Gohari S, et al. Epigenetic signatures in surrogate tissues are able to assess cancer risk and indicate the efficacy of preventive measures. Commun Med (Lond) 2025; 5(1): 97.

2. Herzog CMS, Theeuwes B, Jones A, et al. Systems epigenetic approach towards non-invasive breast cancer detection. Nat Commun 2025; 16(1): 3082.

3. Herzog CMS, Redl E, Barrett J, et al. Functionally enriched epigenetic clocks reveal tissue-specific discordant aging patterns in individuals with cancer. Commun Med (Lond) 2025; 5(1): 98.

4. Widschwendter M, Rosenthal AN, Philpott S, et al. The sex hormone system in carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(12): 1226-32.

5. Haran S, Chindera K, Sabry M, et al. Natural Killer Cell Dysfunction in Premenopausal BRCA1 Mutation Carriers: A Potential Mechanism for Ovarian Carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2024; 16(6).

6. Schramek D, Leibbrandt A, Sigl V, et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor RANKL controls development of progestin-driven mammary cancer. Nature 2010; 468(7320): 98-102.

7. Gonzalez-Suarez E, Jacob AP, Jones J, et al. RANK ligand mediates progestin-induced mammary epithelial proliferation and carcinogenesis. Nature 2010; 468(7320): 103-7.

8. Tharmapalan P, Mahendralingam M, Berman HK, Khokha R. Mammary stem cells and progenitors: targeting the roots of breast cancer for prevention. EMBO J 2019; 38(14): e100852.

9. Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Aragaki AK, et al. Association of Menopausal Hormone Therapy With Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality During Long-term Follow-up of the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA 2020; 324(4): 369-80.

10. Bartlett TE, Evans I, Jones A, et al. Antiprogestins reduce epigenetic field cancerization in breast tissue of young healthy women. Genome Med 2022; 14(1): 64.

11. Yang Z, Wong A, Kuh D, et al. Correlation of an epigenetic mitotic clock with cancer risk. Genome Biol 2016; 17(1): 205.

12. Theeuwes B, Ambatipudi S, Herceg Z, Herzog CM, Widschwendter M. Validation of blood-based detection of breast cancer highlights importance for cross-population validation. Nat Commun 2025; 16(1): 2164.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in