Hidden trade-off in urban health

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Social Sciences, and Physics

When considering healthcare in cities, a familiar contrast comes to mind: residents in larger cities tend to have greater access to healthcare, while those in smaller cities often face limited access. Yet, as often happens when one lets the data speak, the story we uncovered turned out to be more complicated, and far more intriguing, than the standard narrative of “big cities are better”. Most of the research on the gaps in urban-rural healthcare focuses on primary care – an important element of healthcare, but certainly not the only one. What happens when someone needs an oncologist, a neurologist, or a urologist? Do big cities always guarantee better care when it comes to these specialized services?

I asked myself this question as I was preparing my class Complex Urban Systems at the Center for Urban Science and Progress (CUSP) at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering. Lucky enough, I have the fortune and privilege of working with an amazing pool of young researchers. So, it happened that Mechanical Engineering and CUSP Ph.D. student Tian Gan jumped on the idea and began digging data to answer what was just the curiosity of a hypochondriac researcher who spends a lot of time with medical doctors for professional and personal reasons. Tian did an amazing job creating a large and detailed dataset, comprising nearly 1.4 million healthcare providers organized into 75 medical specialties across 898 cities in the United States.

As Tian made strides into her work, she brought onboard Tanisha Dighe, one of our talented M.Sc. students at CUSP to clean and validate the dataset, fill gaps, and begin our research journey. To make sense of the patterns, we turned to classical network science and urban scaling theory -- two tools that I beat to death in my Complex Urban Systems class. Network science is the bread and butter of interdisciplinary physics, and is an area of research that has dominated my career since my post-doctoral training in the seemingly different area of cooperative control of multi-robot teams with Dan Stilwell at Virginia Tech – I am forever indebted to Dan for having me introduced to this amazing topic. Urban scaling has its roots in biological allometries and it was originally developed to understand how infrastructure and socioeconomic output scale with the population size of a city and since then has seen countless applications; to learn more about the topic, I recommend the amazing book by one of its architects, Luis Bettencourt.

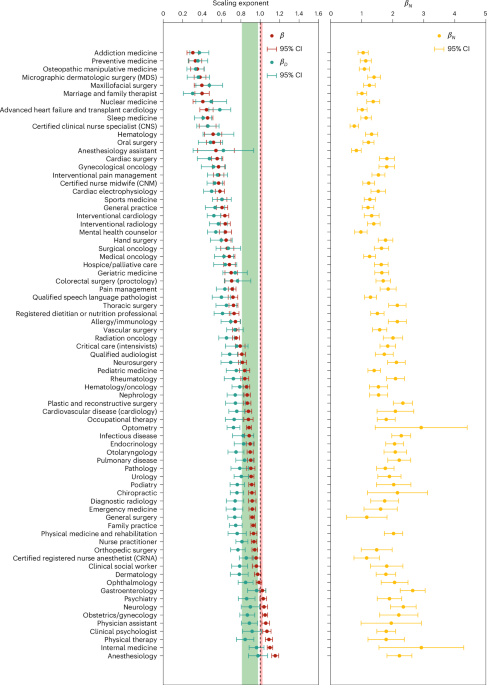

Our findings, published in Nature Cities, were twofold—and somewhat paradoxical. On the one hand, larger cities do offer a broader diversity of specialties. In fact, out of 75 specialties, only two – family practice and nurse practitioners – were present in all cities. The rest of the specialties are more likely to be present as the city population increases. This is intuitive: larger populations tend to result in more cases of rare health conditions, creating demand for rarer specialists. Less intuitively, for most specialties, their per capita availability decreases as the population size grows (what we call sublinear scaling), so that residents of larger cities have access to fewer specialists than residents in smaller cities. Interestingly, the lower the breadth of a specialty (measured via a knowledge-based hierarchical network developed as part of this work), the more dramatic is the sublinear scaling. Together, these findings reveal a hidden trade-off: while larger cities tend to offer a greater diversity of specialists, the number of these specialists may be less in larger than smaller cities.

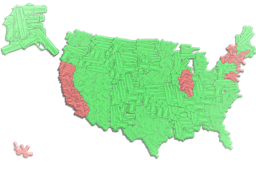

To delve into the potential mechanisms that could underpin behind the paradox, we went back to data collection. This time, Tian collected data on patient encounters and healthcare spending, allowing us to look not only at where specialists are located, but also at how heavily they are needed. Our analysis brought about two potential mechanisms. First, higher patient loading: in large cities, specialists tend to face higher patient volumes, leading to longer waiting times and overburdened schedules. Second, economic clustering: some cities, such as Atlanta and Philadelphia, act as hubs for healthcare due to the presence of medical schools, biotech firms, and research hospitals.

This trade-off has real-world consequences. For example, patients in large cities may wait months to see a dermatologist or oncologist, potentially delaying diagnoses and treatment. Meanwhile, smaller-sized cities may lack entire categories of specialists, forcing residents to travel or go without. Both scenarios reinforce inequalities, especially for vulnerable populations such as the elderly or racial minorities. Our analysis also raises questions about the future of healthcare planning. As U.S. cities continue to grow and populations age, policymakers must anticipate both the benefits and the bottlenecks of urban healthcare systems. Diversity alone is not enough if the provision cannot keep pace.

Ultimately, our paper in Nature Cities suggests that in healthcare, as in much of urban life, bigger is not always better.

Thank you, Tian, for helping me write this blog.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Cities

This journal aims to deepen and integrate basic and applied understanding of the character and dynamics of cities, including their roles, impacts and influences — past, present and future.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in