How Changing Landscapes Could be Fuelling Alpha-Gal Syndrome

Published in Ecology & Evolution, Public Health, and Zoology & Veterinary Science

Imagine being bitten by a tick and, weeks later, finding that a meal of roast beef or lamb sends your body into an allergic shock. This is the reality for those with Alpha-Gal Syndrome (AGS), a condition that causes severe allergic reactions after consuming red meat. In a recent publication in PLOS Climate, Hollingsworth and colleagues look at the ecology and risk factors for AGS. The paper examines how our modern environment might be playing a bigger role in this allergy than previously thought.

The emergence of alpha-gal syndrome

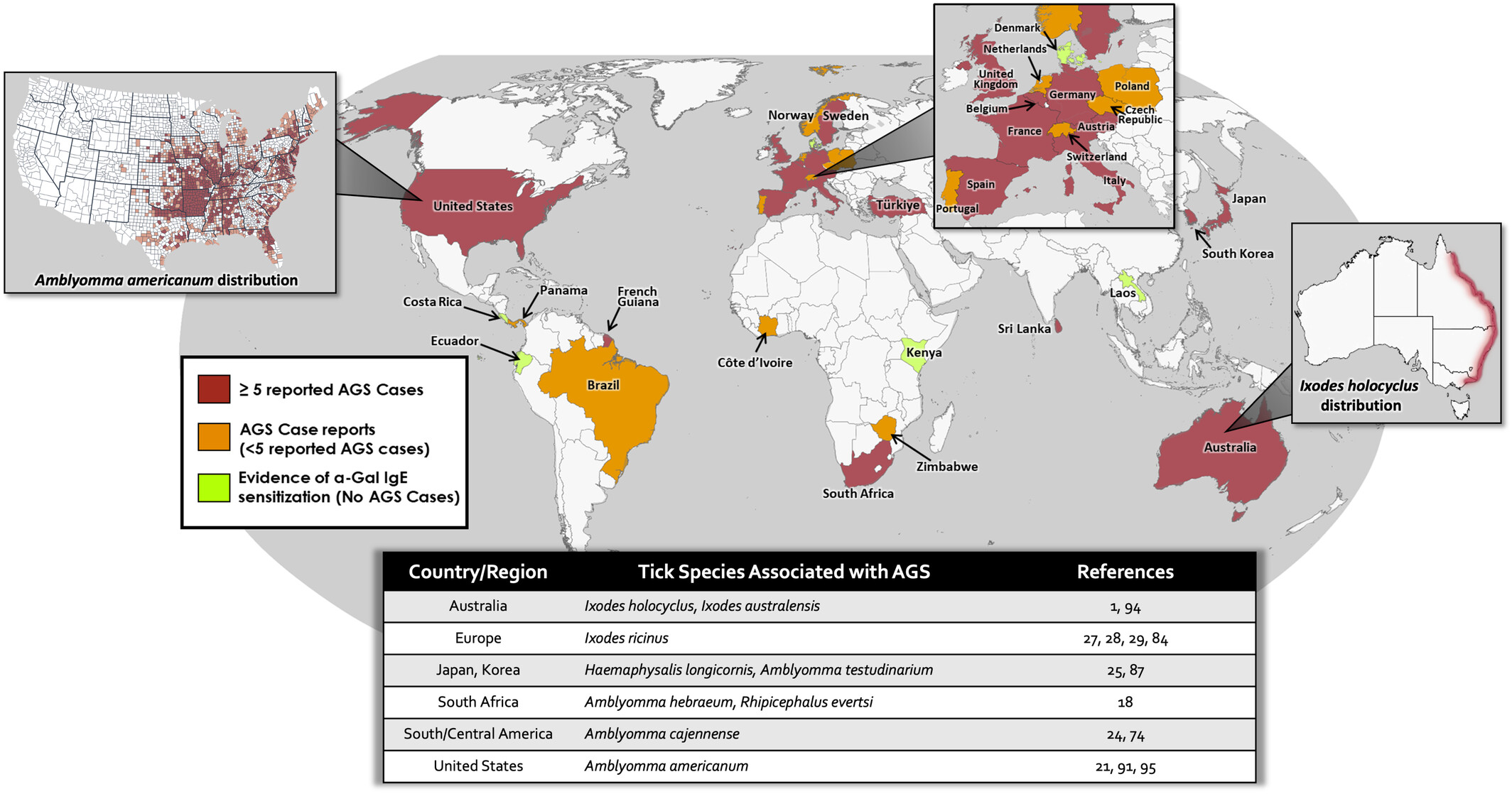

AGS is a relatively recent recognised condition. It unfolds when a bite from certain tick species sensitise the victim’s immune system to a sugar called alpha-gal. This is a molecule that exists in the meat of most mammals but not in poultry or fish, so those affected must steer clear of red meat to avoid potentially dangerous reactions. The ensuing allergic reaction can vary from rashes, nausea and drops in blood pressure, to severe pain and anaphylaxis. Reports of this tick-borne meat allergy have been increasing, even with suspected underreporting.

Source: xpda|Wikimedia Commons, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0, no changes made.

Connecting the dots between our environment and AGS

The study set out to explore whether the places where we live could be influencing our chances of developing this condition. Researchers focused on the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, an area that has seen a rise in reported AGS cases over recent years. They mapped AGS cases and compared them with detailed information about local landscapes, such as habitat fragmentation, land development, and population density.

One of the standout findings was that fragmented landscapes (areas where natural habitats have been broken into smaller, isolated patches) provide a particularly inviting environment for lone star ticks, the species responsible for AGS in the United States. As urban and suburban developments push into these once-continuous natural spaces, the ticks and the animals they depend on are forced into closer contact with human communities. This increased overlap between human and tick habitats means more opportunities for people to get bitten and, eventually, to develop this sensitivity to alpha-gal.

Source: Wilson et al, Allergy. 2024 Jun;79(6):1440-1454 | shared under a CC BY-NC 4.0, no changes made.

Implications for public health and future planning

Not all parts of our environment are equal in the risk they carry. The study highlights that open space developments and regions with lower population density, which often coincide with fragmented habitats, are particularly prone to fostering conditions that enable the lone star tick to thrive. Essentially, when our cities and towns spread into natural areas without careful planning, they create pockets of land where both ticks and humans are more likely to interact.

For public health officials, knowing which areas of development are most vulnerable to housing significant tick populations allows them to direct educational resources and preventative measures where they are needed most. For instance, residents of affected areas might be more informed about the importance of wearing protective clothing when venturing outdoors, regularly checking for ticks, or even landscaping in ways that discourage tick habitation.

The research suggests that the design of urban areas needs more thoughtful planning to maintain larger, more contiguous natural habitats while also designing communities that minimise the overlap between wildlife and human living spaces. By rethinking how we accommodate growth, we may be able to reduce the hidden health risks that come with our expanding development.

.jpg)

Source: Doug Beckers | Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0, no changes made.

Don’t forget to check!

In some places, the most dangerous wildlife you may encounter is ticks. They come in all sizes, with young ticks so small they are frequently compared to poppy seeds, making them hard to spot after you’ve been out on that walk reconnecting with nature. But it’s well worth the effort to check thoroughly and make sure you haven't brought any hitchhikers home.

[featured image: Polly Hutchinson, Flikr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, no changes made]

Follow the Topic

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in