Preventing the re-emergence of kissing bugs and Chagas disease in Arequipa

Published in Public Health

Explore the Research

Page Not Found | PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

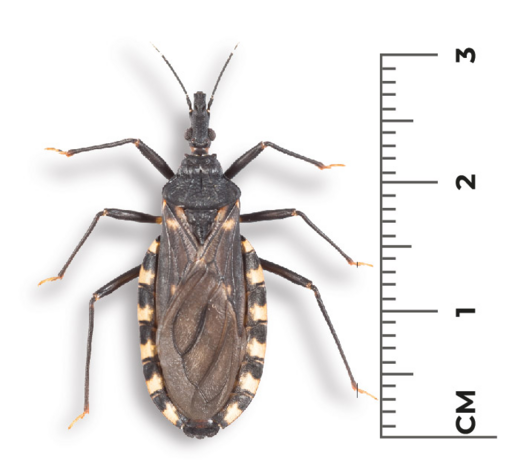

In the south of Peru lies Arequipa, the country’s second largest city and a neighbour to the beautiful Misti, a dormant volcano that attracts tourists all year-round. Arequipa’s historic centre is also well worth a visit, as it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Behind this charm lies a quiet struggle: keeping the Chagas disease vector Triatoma infestans from re‑establishing itself after years of control efforts. A vector control campaign ran between 2003 and 2018, and involved careful planning, insecticide residual spraying, and post-control monitoring. In the latter, surveillance was categorised as passive (residents reporting bugs) and active (Vector Control Specialists inspecting homes).

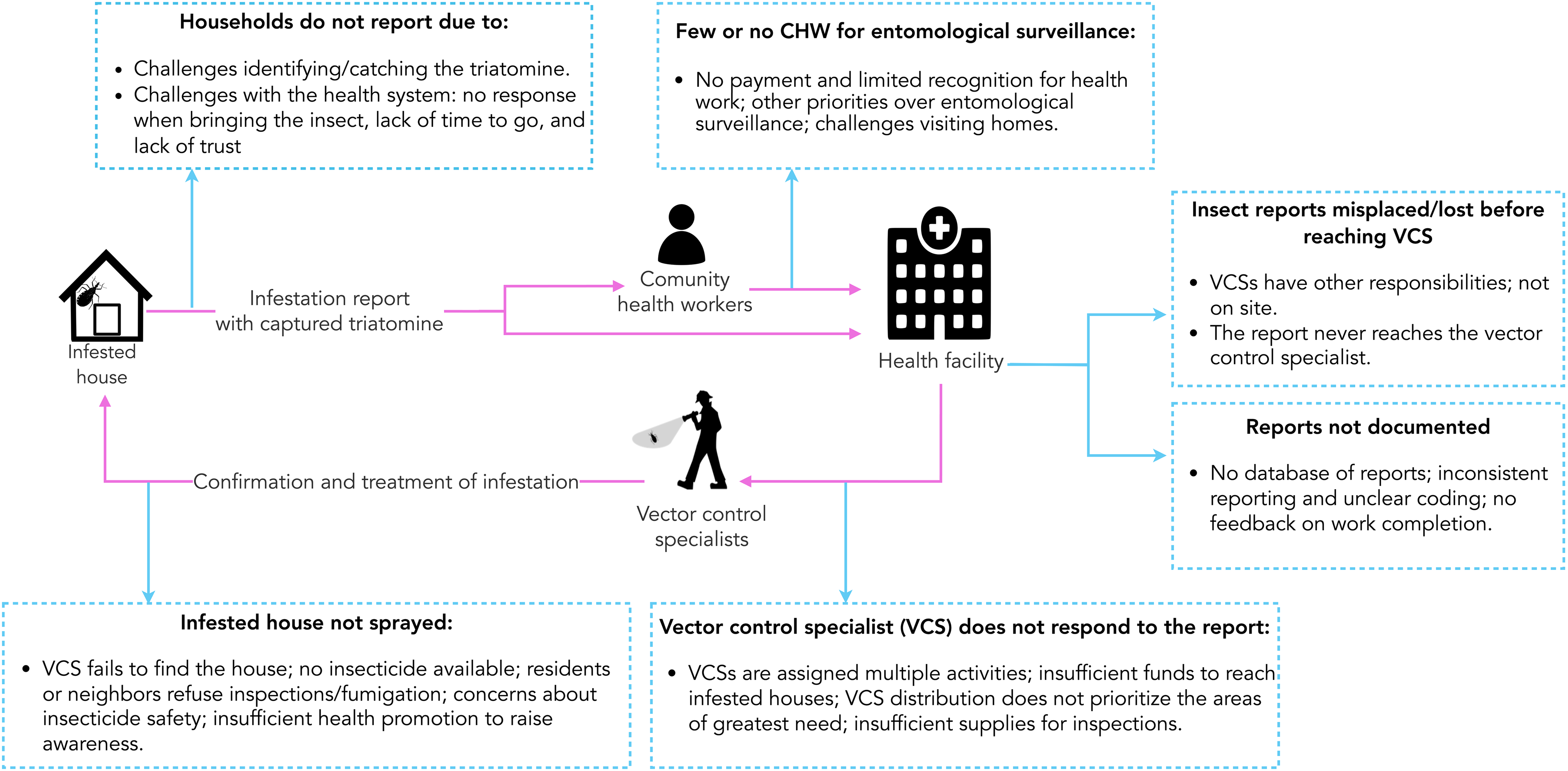

A recent study published by Tamayo and colleagues in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases reveals why this is harder than it sounds. The research team interviewed stakeholders relevant to vector control in Arequipa, from community members to health officials, and mapped the surveillance workflows which helped clarify information respondents and focus.

Interviews and focus groups revealed a myriad of challenges

Even after large‑scale insecticide spraying campaigns dramatically reduced T. infestans populations, the complex surveillance system in place faces barriers at multiple levels:

- Reporting problems were described by several respondents, with residents expressing difficulties in capturing and delivering triatomines to health facilities. Reporting challenges included no clear handling of triatomines or reports coming in, informing the right staff, or concerns being dismissed.

- Vector Control Specialists (VCS) worried about the deficiency of resources, transportation, or equipment. They were often asked to take on other roles (e.g., sanitation, water quality, health facility assistance) which also restricted their time spent in active triatomine surveillance and the degree of effort invested in the home inspections.

- Community Health Workers (CHW) also felt a lack of financial support and recognition for the work they do, incentivising them to focus their time and efforts in other health programmes where they are better remunerated. Sometimes the CHW are not well known by residents or VCS, which further affects engagement with the communities.

Budget challenges were common within the national and regional health systems as well, and prioritisation of other health issues means very little funding trickles into these vector surveillance programmes. All these problems are further complicated by the absence of clear guidelines that can support decision-making and planning by all the stakeholders involved.

Source: Centro Nacional de Diagnóstico e Investigación en Endemoepidemias. Centro de Estudios Parasitológicos y de Vectores (2023). Catálogo de triatominos argentinos. 1era edición.

Why this matters

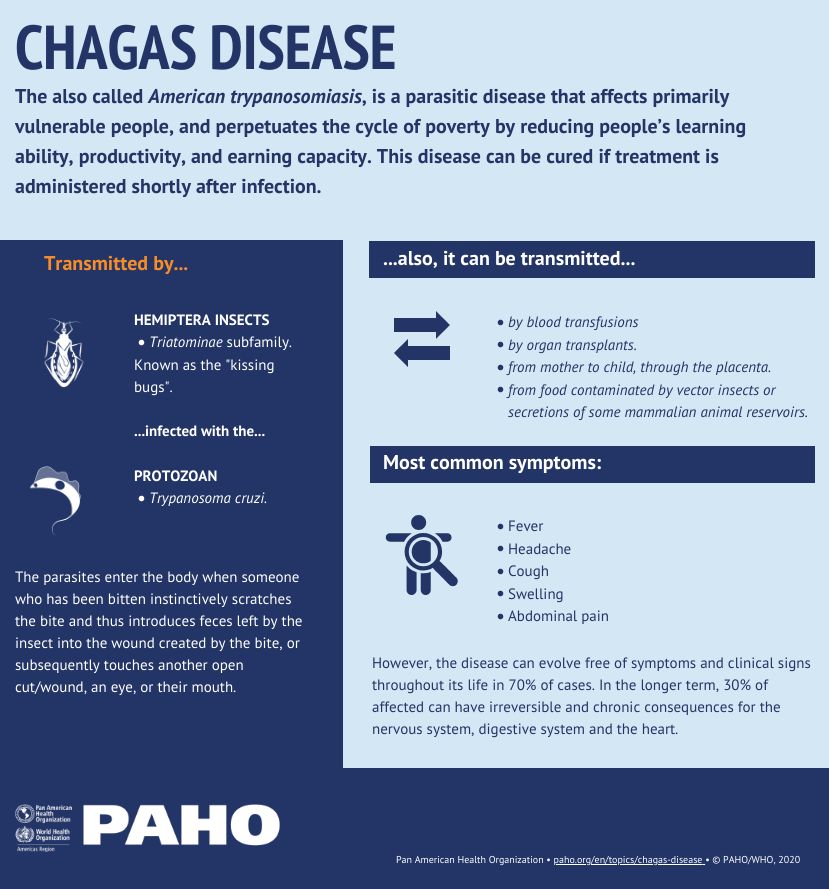

Chagas disease, caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, can lead to serious heart and digestive problems if untreated. Once vectors re‑establish in an area, controlling them becomes far more costly and difficult. The authors highlight this problem is not unique to Peru, stating “[…] the efficacy of triatomine control programs is compromised by a lack of sustained political commitment, decentralization of disease control programs, a reduction in trained personnel and budget competition across other vector-borne disease control program”.

Arequipa’s experience shows that even after apparent success of triatomine control, vigilance must be maintained, and that requires systems that are both technically sound and socially embedded. Providing a ray of hope, new vector control strategies have recently been tested in Arequipa, where cluster randomised trials showed how a reframing of the surveillance system increased their capacity to detect hotspots and focus resources. Disappointingly, local policies impede dissemination of the promising approach.

In their paper, Tamayo and colleagues argue for better data tools tailored to vector control, enabling faster, more accurate responses; risk‑based inspection targets rather than arbitrary quotas assigned to VCS staff; stronger community engagement; and sustained investment in trained personnel and operational capacity.

It is crucial to remember that vector‑borne diseases can re‑emerge if surveillance systems weaken, and that people are an essential part of the solution. Their local knowledge, lived experiences, and participation can be as critical as insecticides and treatments. Involving communities prevents the mistake control programmes have historically made: face ignoring local realities.

Arequipa’s story is a reminder that public health victories are rarely permanent without resilient systems behind them. Adequate investment, guidance and support will ensure that the beauty of this Peruvian city is not shadowed by the return of a preventable disease.

Follow the Topic

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in