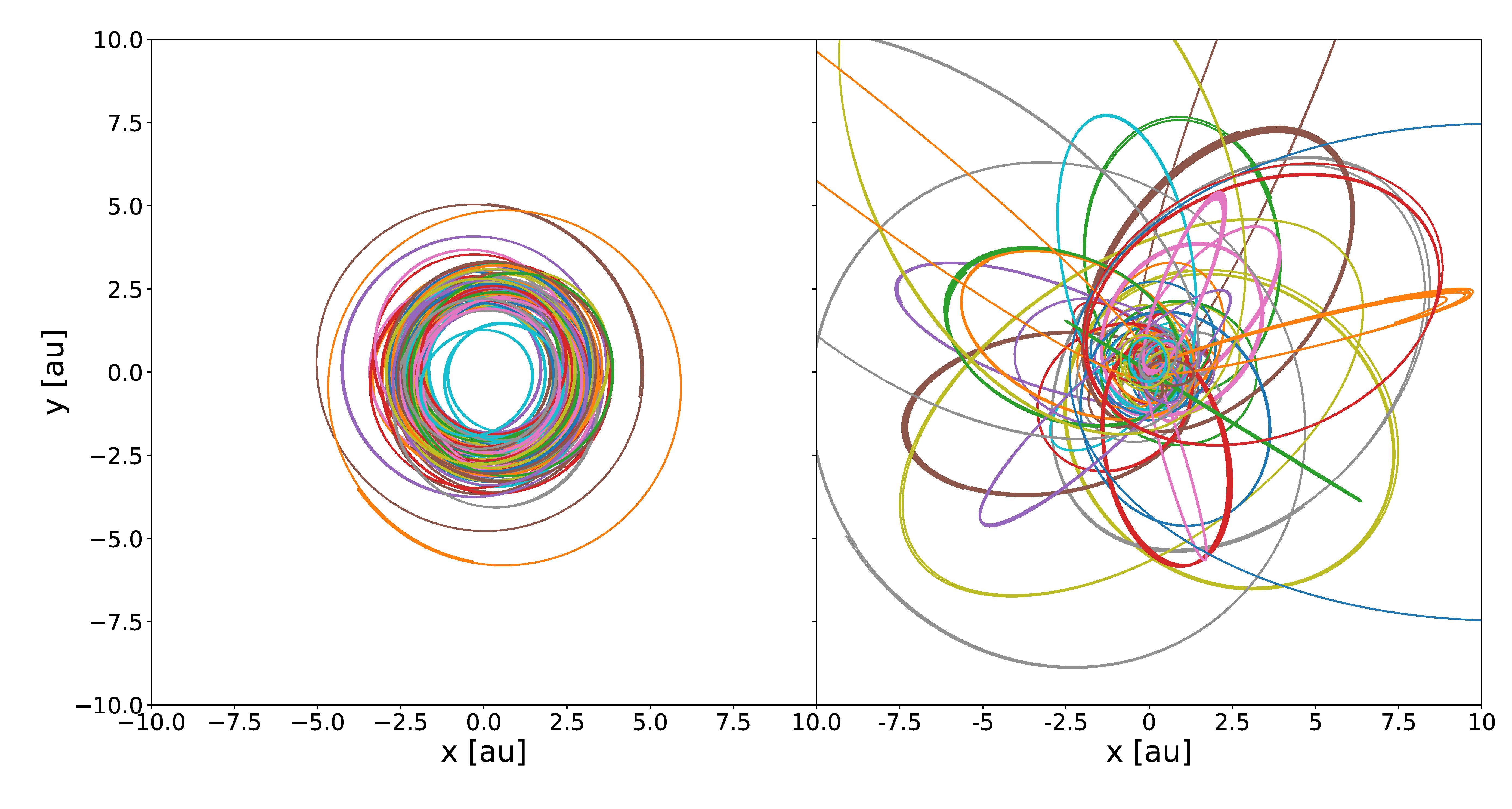

The evolution of the orbits of planets and asteroids in the Solar

system is chaotic. This means that minuscule changes in their orbit

eventually leads to extraordinary variance in their positions. In the

case of asteroids, this could be the difference between hitting or

missing the Earth.

In the classical, Monte-Carlo, approach collision probabilities are

determined by launching thousands, and even sometimes millions, of

asteroids according to distributions in orbital parameters defined by

the asteroids' respective observed uncertainties. The collision

probability is then determined by the fraction of asteroids that

strike Earth or approach with a certain minimum distance of it. When

objects experience a close encounter with a planet, or when their orbits

are particularly uncertain, this method fails to accurately quantize

the collision probability because it does not fully explore the space

of all possible outcomes; one simply cannot perform enough simulations

of asteroid trajectories in order to arrive at a finite number of

asteroids that would actually hit the Earth.

By performing detailed calculations of the orbits of planets and

hypothetical asteroids, we acquire a library of asteroids that will

collide with Earth in the near future, which we refer to as "known

impactors". For this calculation, we first compute the orbits of the

planets forwards in time up to 10,000 years in the future. In the next

step, we then calculate the future solar system backwards in time

while launching asteroids from the Earths' surface. This then creates

a collection of objects that will collide with Earth once their

velocities are negated. These known impactors are then used as

examples of hazardous objects to train the neural network.

This neural network, called HOI (meaning "hello" in Dutch), is trained

to distinguish known impactors from real, observed, asteroids. The

accuracy of HOI in identifying known impactor is, however, not

perfect, as it sometimes confuses one class of objects for another.

The observed objects that are confused for known impactors are

considered "potential impactors" because their orbits are similar to

virtual objects that we know will strike Earth. Out of the identified

potential impactors, we are especially interested in the large

objects, which are dangerous for life in Earth, and those objects with

uncertain orbits, which can be overlooked by the Monte-Carlo approach.

We can then further study this subset of potential impactors through

classical means of evaluations to better quantify their respective

probabilities of impact.

Once trained, HOI was able to process all the virtual and observed objects in a few seconds recognizing 95% of the known impactors and 91% of the potentially hazardous objects held out of the training process. The performance of HOI was further verified by a class of MSc students at Leiden Observatory as part of a project for the "Deep Learning in Astronomy" course. Given the set of observed objects and known impactors, the students were able to independently reproduce the results of HOI, indicating that the results are quite robust.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in