Indo-European Origins: A new Solution to an old Puzzle

Published in Social Sciences, Genetics & Genomics, and Arts & Humanities

by Iosif Lazaridis, Nick Patterson, David Anthony, Leonid Vyazov, and David Reich

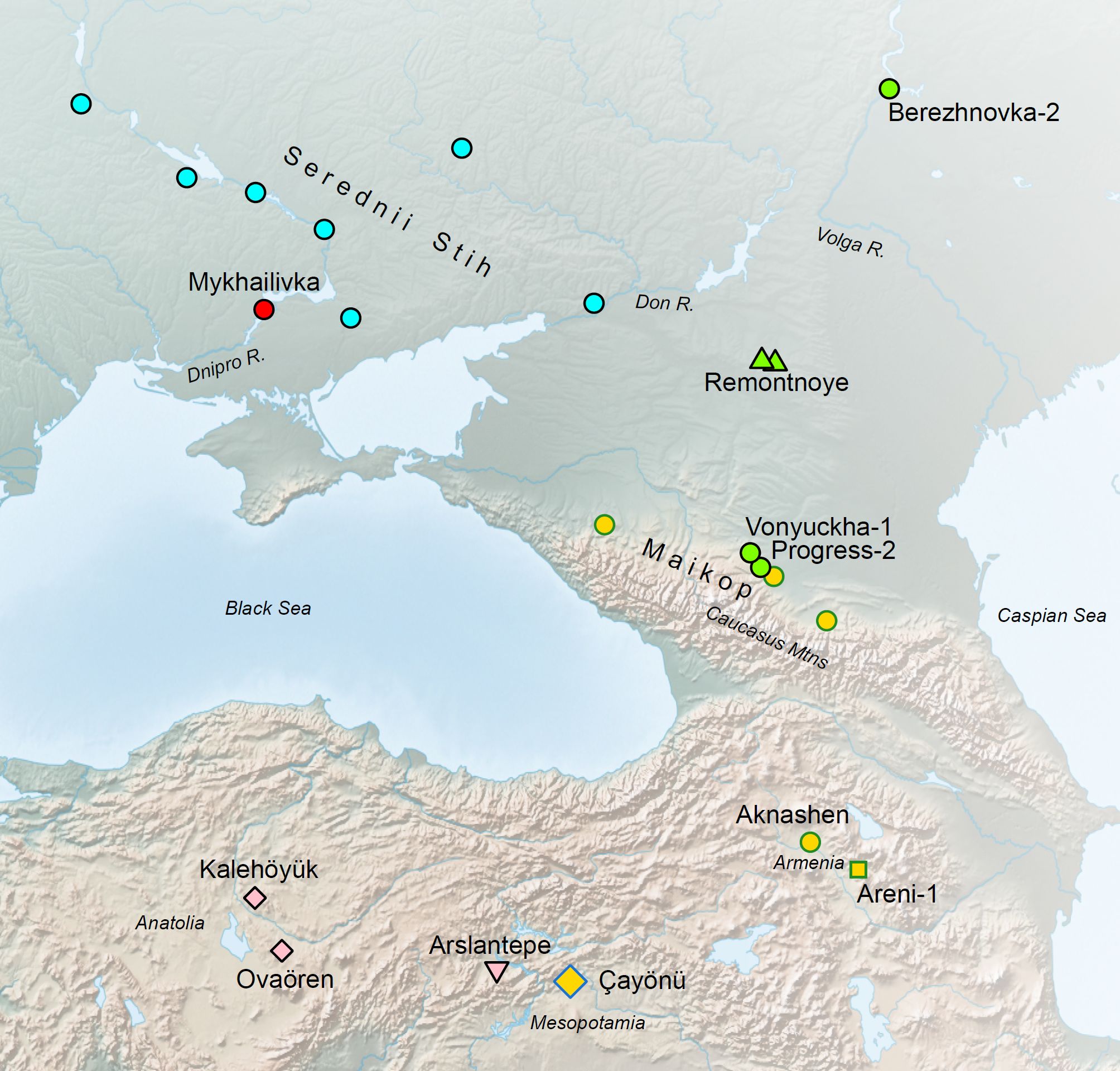

Poster Image: A 40-45 year old man buried in Ulan-4, kurgan 3, burial 12 near the village of Remontnoye around 4000BCE (Image by co-author Natalia Shishlina).

A fortuitous meeting

Nick Patterson, a geneticist at the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard, gave a talk in 2010 at an Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) workshop organized by the Eurasian steppe historian Nicola di Cosmo, in which he used new statistical methods1 on genetic data of present-day people to infer a population movement into Europe from Central Asia around 3100 BCE. David Anthony had written The Horse The Wheel and Language2 as an IAS fellow, in which he argued that pastoralists of the Yamnaya culture on the European steppe around 3000 BCE had spoken the Proto-Indo-European language ancestral to diverse modern languages like English, Armenian, and Hindi. Anthony’s work presented a detailed argument about how horse domestication, aided by wheeled vehicles and possibly horse riding, had an economic multiplier effect that drove the Yamnaya expansion, but his ideas faced a challenge from a relatively new theory3 advanced by the late Sir Colin Renfrew who identified Anatolian agriculturalists ~7,000 years ago and their well-documented expansion across Europe as the first Indo-Europeans. Talking extensively during the workshop, Anthony and Patterson realized that their quite different lines of evidence, genetic and archaeological, could be pointing to the same event two millennia after the agricultural expansion.

Anthony had co-directed NSF-funded archaeological excavations in the middle Volga steppes of Russia during the Yeltsin presidency and the first Putin term when this was briefly possible. He and his colleagues had sampled 66 archaeologically recovered individuals stored in the city of Samara, including 14 from Yamnaya-culture kurgan graves, to obtain a time-series of radiocarbon dates and stable dietary isotopes as a record of dietary change in the Volga-Ural steppes between 5500-1500 BCE. After being drilled for dates at Arizona and isotopes at Oxford, the returned bone remnants sat in the back of a drawer in the Anthropology Lab at Hartwick College in Oneonta, NY waiting for new methods to arrive.

Patterson and his decade-long collaborator David Reich, head of a genetics lab at Harvard Medical School, were the harbingers of such new methods. They were at the time working with Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, Germany analyzing ancient DNA of Neanderthals and Denisovans.4 Reich, inspired by this work and by his lifelong interest in the past,5 was building his own ancient DNA facility, aiming to tackle more recent questions of human history, such as the question of who the first Indo-Europeans were.

Co-authors David Reich and Nick Patterson during a 2014 Science of the Human Past lecture on European origins. Credit: Kris Snibbe/Harvard University.

A massive migration surprise

Iosif Lazaridis, a new postdoc in David Reich’s lab suspected that central European samples around the time predicted by Anthony’s theory might hold the answer. He had previously discerned6 “Ancient North Eurasian”1 (ANE) ancestry in modern Europeans that was lacking in an ~8,000 year old hunter-gatherer man from Luxembourg and a ~7,000 year old Neolithic farmer woman from Germany, but sometimes joked at the presumption of trying to model Europeans across space and time with only these two ancient Europeans and a ~24,000 year old boy from Siberia7 as the sources. Nonetheless, if the ANE signal represented by the Siberian boy was real, the timing and strength of its arrival could be found by examining a detailed time transect of ancient samples from Central Europe. By a stroke of luck, Wolfgang Haak, ancient DNA pioneer then at the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, had assembled precisely such a series, and collaborated with Reich to study them in the new Harvard lab.

The first people in central Europe to show ANE ancestry were those of the Corded Ware culture around 2500 BCE. Lazaridis discovered that the Yamnaya contributed to them the right blend of ancestry that included ANE but also West Asian ancestry absent in the farmers and hunter-gatherers. The timing was also right and consistent with the migrations predicted by Anthony and Patterson. But, the scale of population turnover at 75% was unbelievable: this wasn’t a case of tiny kurgan-buried elites dominating the farmers of “Old Europe” that Marija Gimbutas had written about,8 but a massive change well outside the contemporary archaeological consensus. Independent confirmation came when the team’s article was published9 together with a parallel study10 by Morten Allentoft, Martin Sikora, and Eske Willerslev’s competing Copenhagen team that reached similar conclusions.

Follow-up work has traced movements of Yamnaya into Greece11,12 where their ancestry was found in Mycenaean Greeks but not in people of the Minoan civilization, Albania,12 and Armenia12 among putative Proto-Armenians but not among their Urartian-speaking neighbors13. Yamnaya descendant cultures impacted regions well beyond the steppe across Europe and Asia: The Bell Beaker culture into western Europe,14 including to Britain,15 Iberia,16 France,17 and Italy18; and the Corded Ware culture into both Europe8,10,19 and, via Fatyanovo20-Sintashta-Andoronovo intermediaries, into Central/South Asia21 contrasting Indo-Aryan from Dravidian speakers.

A hidden early history

Many people signed on to the “Yamnaya as Proto-Indo-Europeans” hypothesis on the strength of the mounting genetic evidence but the theory failed to explain Anatolian languages, such as Hittite, which were deeply divergent from their Indo-European relatives by perhaps a thousand years.22,23 Genetic data on ancient Anatolian samples accumulated,11,24,25 but showed little to no evidence of steppe migrations. Something different had happened in Anatolia.

We would solve this problem while trying to understand the origins of the Yamnaya themselves. This was no easy task as the extreme mobility of the Yamnaya meant that within generations of their appearance they had expanded across 5,000km from Hungary in the west to Mongolia in the east. In our study we analyzed 286 individuals from more than 100 sites across the entire geographic range to complement the handful of sites previously published. Where across the vast swathe of this distribution did the Yamnaya come from? Some of the 161 Eneolithic (pre-Yamnaya) people, about half newly sequenced in our study, might hold the answer.

The combined dataset, meticulously documented by Anthony (with the help of the encyclopedic knowledge of eastern European archaeology by Leonid Vyazov) and Alexey Nikitin at Grand Valley State University (who co-ordinated the work and interpretation of samples from Ukraine and Moldova) represents a leap in the archaeogenetics of the steppes and the combined work of our many colleagues. Their spirit of scientific inquiry and co-operation stands at a stark, but hopeful contrast against the realities of the ongoing war raging across the landscape once united by Yamnaya travelers.

Riverine clines across the steppe

Patterson saw that the core Yamnaya cluster was homogeneous and clearly at one end of a cline of ancestry that included hunter-gatherers from Ukraine on its opposite end, framing people of the Eneolithic Serednii Stih culture of the Dnipro-Don area in the middle. The Yamnaya seemed to be simply a late Serednii Stih population. Plotted on a map, this cline was centered on the Dnipro and was distinct from another cline that followed the Volga river passing through the Samara valley that had furnished the first Yamnaya ancient DNA results. Samara and the Volga were thus not where the Yamnaya were formed: the answer was in the west, in the part of the steppe north of the Black Sea.

Our analysis showed that the Yamnaya population was formed by admixture around 4000BCE and expanded after 3300BCE. The “core Yamnaya” group emerged from a small founding population of just a couple of thousand people between 3700-3300 BCE, then expanded explosively in just a few centuries, breaking connections between geography and genetics so that descendants in Hungary and Mongolia were almost as closely related to each other as people buried just a few hundred kilometers apart. The oldest core Yamnaya individual, from the site of Mykhailivka in Ukraine (described in the related article in Nature by Nikitin, Lazaridis et al.), dated to around 3600-3400 BCE, was from one of the few sites where there was undisrupted settlement from Copper Age to Yamnaya times, making this a candidate for the location where the Yamnaya formed from their genetically nearly identical but culturally quite different predecessors, the Serednii Stih culture of the Dnipro-Don area.

Indo-European languages were spread by the Yamna (Ukrainian)/Yamnaya (Russian) culture that emerged in the territory of the Serednii Stih culture of the steppe north of the Black Sea. Deeper in time, these people had ancestry from the Caucasus-Lower Volga frontier zone and genetic cline (Aknashen-Maikop-Remontnoye-Berezhnovka). People from this cline also spread southwards and can be detected along the path (Areni-1-Arslantepe-Ovaören-Kalehöyük) leading to the (now extinct) Anatolian language speakers.

Between the Caucasus and Lower Volga

Where did the languages of the Yamnaya come from? Patterson identified a close relationship between people buried at Progress-2 and Vonyuchka-127 in the North Caucasus piedmont and new samples well to the north at Berezhnovka-2 in the Lower Volga. Clearly these people were moving great distances between the Caucasus and the steppe river valleys. They wandered as far west as Moldova and Hungary, and northwards too, mixing with the EHG locals along the Volga in the famous site of Khvalynsk26 and elsewhere to form the Volga cline.

One group of them, reaching the steppes north of the Black Sea, and mixing with local hunter-gatherers there to form the Serednii Stih and Yamnaya, was different: they carried not only Berezhnovka but also, Patterson realized, ancestry related to the Copper Age people of Armenia. Lazaridis zeroed in on two individuals sampled near the village of Remontnoye ~4000 BCE halfway between Caucasus and Volga as possible Yamnaya ancestors; these were made of an even Berezhnovka-Armenian (or Caucasus Neolithic) mix. The rich Maikop27 culture that flourished during the 3000s BCE in the North Caucasus was part of the same mix but with more Caucasus Neolithic ancestry. There was a “Caucasus-Lower Volga” (CLV) cline of ancestry with Neolithic Armenia on one end and Berezhnovka people on the other. The Yamnaya had about four fifths of their ancestry from this cline. The Black Sea steppe was where the Yamnaya grew to maturity during the 3000s BCE but many of their ancestors had wandered there from the Caucasus-Volga zone during the 4000s BCE.

The final piece of the puzzle

Lazaridis had previously studied people of the “Southern Arc” who lived in the Balkans, Anatolia, and Armenia (south of the steppe),12 concluding that since both Yamnaya and Anatolians had ancestry from the Caucasus and neighboring West Asian highlands, the “missing link” between the two might be found in the area. He doubted that a more specific link could be discerned amidst the waves of migrations from the Caucasus and Mesopotamia that had enveloped a multilingual Anatolia for thousands of years before the appearance of the Hittite texts, but when Reich and Patterson suggested that he revisit the question in the light of the discoveries on the steppe, the answer surprised all of us.

Half a dozen individuals buried near the Halys river (modern Kızılırmak) in Central Anatolia24 stood out among their contemporaries in possessing a sliver of about a tenth Berezhnovka ancestry, the rest coming from Mesopotamian farmers.28 Alwin Kloekhorst had proposed22 that the crossing of the Halys river was a final step in a long “Anatolian trek” from the west. Our results find putative Anatolian speakers in just the right time and place but the Mesopotamian ancestry and Berezhnovka traces in Bronze Age people from Arslantepe25 in eastern Turkey, Areni-1 in Armenia,29 and Maikop27 in the North Caucasus, reverse the direction. This eastern entry hypothesis resembles Kristian Kristiansen’s maritime entry scenario,30 but proposes that CLV people crossed the Caucasus leaving breadcrumbs we can detect along an inland route, mixing with native people of Mesopotamia and its environs before finally reaching Central Anatolia.

A people of the frontier

The long argument between those who put Indo-European origins on the steppes or in Anatolia and the Caucasus is solved: both are partly right. The oldest phase of Proto-Indo-European, the Proto-Indo-Anatolian parent of both Anatolian and all later branches (Yamnaya) was located at the interface between the steppe and the sown. Some of these diverse ancestors contributed the seeds of their language, others key technologies like the wheel, others key domesticated animals like horses or cattle or goats, others aspects of social organization that facilitated their expansion. Integrative institutions that were central structures in later Indo-European societies, including fosterage (sending sons to be raised by their paternal aunt’s husband, an outsider to the paternal kin group), guest-host and patron-client relations, might have evolved to manage conflict and promote cooperation in a region with extreme social and genetic diversity.

It was not inevitable that the Yamnaya, one group among so many in the Eneolithic steppe, should be the ones to assemble the full “package” of technology and organization that allowed them to be so successful. There was nothing inherently “superior” about either their genes or culture that was the reason for their success, but rather the lucky accident of being in the right place at the right time to combine all these diverse elements of culture and technology into a way of life that advantaged them long enough to make an outsized impact on later generations.

Neither the Yamnaya nor their CLV ancestors were the victorious pure-blooded supermen of 19th-20th century legends.31 The Anatolian languages survived for centuries in the competition of empires, but largely disappeared from memory in Hellenistic-Roman Anatolia before their written records were finally linked to Indo-European in the beginning of the 20th century.32 The Yamnaya largely superseded the CLV and were in turn superseded by scions of the Corded Ware they had founded. The Yamnaya were made up of multiple strands of ancestry that formed them on a genetic and cultural frontier and, during the centuries of their ascendance they opened frontiers of their own beyond the steppe. In so doing they transmitted some of their genes, but most importantly their language, to half the world’s living inhabitants who continue their legacy today.

References

1 Patterson, N. et al. Ancient Admixture in Human History. Genetics 192, 1065-1093, doi:10.1534/genetics.112.145037 (2012).

2 Anthony, D. W. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. (Princeton University Press, 2010).

3 Renfrew, C. Archaeology and language: the puzzle of Indo-European origins. (CUP Archive, 1990).

4 Reich, D. et al. Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Nature 468, 1053-1060, doi:10.1038/nature09710 (2010).

5 Reich, D. Who we are and how we got here: Ancient DNA and the new science of the human past. (Pantheon, 2018).

6 Lazaridis, I. et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature 513, 409-413, doi:10.1038/nature13673 (2014).

7 Raghavan, M. et al. Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans. Nature 505, 87-91, doi:10.1038/nature12736 (2014).

8 Gimbutas, M., Dexter, M. R. & Jones-Bley, K. The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles from 1952 to 1993. (Institute for the Study of Man, 1997).

9 Haak, W. et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 207-211 (2015).

10 Allentoft, M. E. et al. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 522, 167-172, doi:10.1038/nature14507 (2015).

11 Lazaridis, I. et al. Genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans. Nature 548, 214-218, doi:10.1038/nature23310 (2017).

12 Lazaridis, I. et al. The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe. Science 377, eabm4247, doi:10.1126/science.abm4247 (2022).

13 Lazaridis, I. et al. A genetic probe into the ancient and medieval history of Southern Europe and West Asia. Science 377, 940-951, doi:10.1126/science.abq0755 (2022).

14 Olalde, I. et al. The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature 555, 190-196, doi:10.1038/nature25738 (2018).

15 Patterson, N. et al. Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age. Nature 601, 588-594, doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4 (2022).

16 Olalde, I. et al. The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years. Science 363, 1230, doi:10.1126/science.aav4040 (2019).

17 Seguin-Orlando, A. et al. Heterogeneous Hunter-Gatherer and Steppe-Related Ancestries in Late Neolithic and Bell Beaker Genomes from Present-Day France. Current Biology 31, 1072-1083.e1010, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.015 (2021).

18 Saupe, T. et al. Ancient genomes reveal structural shifts after the arrival of Steppe-related ancestry in the Italian Peninsula. Current Biology 31, 2576-2591.e2512, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.022 (2021).

19 Papac, L. et al. Dynamic changes in genomic and social structures in third millennium BCE central Europe. Science Advances 7, eabi6941, doi:doi:10.1126/sciadv.abi6941 (2021).

20 Saag, L. et al. Genetic ancestry changes in Stone to Bronze Age transition in the East European plain. Science Advances 7, eabd6535, doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd6535 (2021).

21 Narasimhan, V. M. et al. The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia. Science 365, eaat7487, doi:10.1126/science.aat7487 (2019).

22 Kloekhorst, A. in The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited: Integrating Archaeology, Genetics, and Linguistics (eds Eske Willerslev, Guus Kroonen, & Kristian Kristiansen) 42-60 (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

23 Kassian, A. S. et al. Rapid radiation of the inner Indo-European languages: an advanced approach to Indo-European lexicostatistics. 59, 949-979, doi:doi:10.1515/ling-2020-0060 (2021).

24 de Barros Damgaard, P. et al. The first horse herders and the impact of early Bronze Age steppe expansions into Asia. Science 360, eaar7711, doi:10.1126/science.aar7711 (2018).

25 Skourtanioti, E. et al. Genomic History of Neolithic to Bronze Age Anatolia, Northern Levant, and Southern Caucasus. Cell 181, 1158-1175.e1128, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.044 (2020).

26 Anthony, D. W. et al. The Eneolithic cemetery at Khvalynsk on the Volga River. Praehistorische Zeitschrift 97, 22-67 (2022).

27 Wang, C.-C. et al. Ancient human genome-wide data from a 3000-year interval in the Caucasus corresponds with eco-geographic regions. Nature Communications 10, 590, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8 (2019).

28 Altınışık, N. E. et al. A genomic snapshot of demographic and cultural dynamism in Upper Mesopotamia during the Neolithic Transition. Science Advances 8, eabo3609, doi:10.1126/sciadv.abo3609.

29 Lazaridis, I. et al. Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East. Nature 536, 419-424, doi:10.1038/nature19310 (2016).

30 Kristiansen, K. The Archaeology of Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Anatolian: Locating the Split. in “Dispersals and Diversification: Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Early-Stages of Indo-European (eds. M. Serangeli & Th. Olander), Leiden – Boston: Brill, 2020.

31 Poliakov, L. Le mythe aryen: essai sur les sources du racisme et des nationalismes. (Calmann-Lévy, 2014).

32 Hrozný, B. Die Lösung des hethitischen Problems. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 56, 17-50 (1915).

Follow the Topic

-

Nature

A weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology on the basis of its originality, importance, interdisciplinary interest, timeliness, accessibility, elegance and surprising conclusions.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in