Integrating devices into diagnostic ecosystems

Published in Microbiology

“It's not just about the tests and which tests you invest in, it's about how they’re going to work and how they’re going to fit in the system” (Dr Cédric Yansouni).

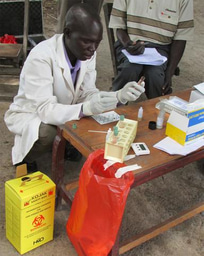

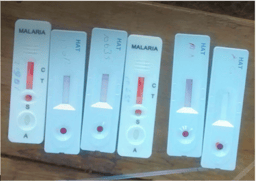

It is clear that we have reached a point where we are to some extent ‘tool ready’ to address major diseases such as ‘the big three’ (HIV, TB, and malaria), some Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs), and even universal threats of Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and pandemic diseases. In many cases, we have the technology, but not the systems to deliver them where they are most needed. By now it is evident that “science and technology is not the issue. It's the rest of the ecosystem; the neglect, the under-investment, that countries don’t identify these as a problem worth investing in" (Prof Madhukar Pai).

Large sobering events such as outbreaks of Ebola in West and Central Africa, or the Nipah virus outbreak in Kerala, India, urge us to think about effective responses, and how they rely not only on available devices, but on a number of different activities and actors. “We are doing these kinds of things for other diseases”, commented Dr Trevor Peter, Senior Scientific Director of the Clinton Health Access Initiative, on the establishment of international global health frameworks such as the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), “but it's boring and dry”, and is therefore less visible and goes unnoticed. This question of the relationship between technology and systems is at the heart of the DiaDev project, and underpinned a workshop we held in Edinburgh in 2014. The discussions that took place at the Summer Institute in 2018 showed, in part because of the high quality social science research that has been undertaken on PoC diagnostics, this question has become mainstreamed and a key consideration for any attempt to deploy diagnostics in low and middle income countries.

Professor Paul Drain of the University of Washington prompted us to think about the wider medical diagnostic system, and “the many links in the chain that have to work together” including planning and assessment, budgeting, and technology assessment, that all has to be coordinated while individual Ministries of Health have to try to coordinate what is actually being used in individual clinics. Harvard University’s Dr Prashant Yadav focused on the supply chain aspect of this assemblage, “a system consisting of the organisation of people, technologies, activities, information and resources involved in making a product reach the customer”. Here, concerns surrounding how poorly functioning supply chains are often framed as the result of corruption in developing countries is misleading, as “a bigger influence is actually the nature of uncertainty [which] creates a vicious cycle where we never get to fully understanding what the end user needs”.

Never far from the problem of implementing diagnostics is what we do with the knowledge they produce, and how this evidence can be harnessed and optimised. Dr Trevor Peter brought focus back to the importance of data, not just in terms of connectivity and directionality, which emerged as key topics during the Tech Pitch presentations, but the power of data in convincing and mobilising stakeholders to take action on an issue. “We are in the business of generating data […] diagnostics is at the beginning, the data is critical for the response from beginning to end”.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 715450.

The author would like to thank Professor Madhukar Pai and Dr Alice Street for their helpful comments and input on this series. The author acknowledges the lands of the Abenaki/Abénaquis, Haudenosauneega, Huron-Wendat, Kanien'kehá:ka, and Mohawk on which the Summer Institute takes place.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in