Where landscapes collide: adapting global health diagnostics to local contexts

Published in Microbiology

Beyond the regulatory barriers to bringing devices to market, another challenge is how to negotiate the trade-offs between generalisability and local relevance. At one end of the spectrum products must be broadly applicable enough to have a viable market, while at the other we need to make sure tests and interventions are locally adapted and suited to regional needs and contexts. “Say you want to do a febrile panel” commented one discussant during a Q&A session, “in every country that is something different. Do you make a broad one and not make much money? Or multiple specific ones?” Participants largely agreed that many of the devices needed are already developed and exist, but are not adapted to local contexts and fail to reach the frontline in many LMICs where they are needed. As Dr Cédric Yansouni foregrounded his presentation on the role of centralised reference labs, the dichotomy of “point of care versus point of ‘can’ ” need not be mutually exclusive goals, we can and ought to strive for both.

Others talked about managing the trade-off between having a high quality test that has a small market, and a less specific test but which actually reaches the people who need it. One participant suggested relaxing regulatory hurdles and the pre-qualification processes in countries that can’t afford to achieve them, asking “is this something central governing bodies can address alone? Where does industry fit into a solution?”. The trade-off between having high performing tests accessible to fewer people, compared with imperfect ones available to many who need them was a sticking point for several discussions surrounding quality and accessibility.

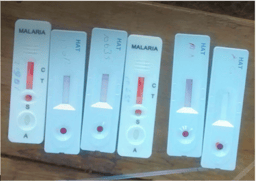

Could one way of reconciling this gulf be simply producing more multiple-disease testing platforms? Or do we need to try and find ways of making it easier to move manufacturing toward making diagnostics for the global south by the global south? Where western companies in the global 'north' tend to fit their models to serve low and middle income countries, is it possible to invert this relationship? “Why don’t we have good diagnostic companies in these countries making diagnostics for low and middle income countries?” Prof Pai asked a panel on how product developers were addressing needs. Representatives from industry responded, citing the costs of production and quality assurance involved in making devices in the US, pointing to a lack of comparable examples in LMICs - “a lot of our manufacturing is highly automated, so our costs are tightly controlled. Talking about moving that to another country makes it very expensive. It’s not really a viable option in many cases” (Duncan Blair, Abbot). However as Philippa Makobore, Head of department at the Uganda Industrial Research Institute argued, specific countries should too be responsible for implementing regulation for devices, citing a merger between a Ugandan and Indian pharmaceutical company producing malaria drugs and ARVs as an example where low resource countries are already manufacturing and selling products to others.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 715450.

The author would like to thank Professor Madhukar Pai and Dr Alice Street for their helpful comments and input on this series. The author acknowledges the lands of the Abenaki/Abénaquis, Haudenosauneega, Huron-Wendat, Kanien'kehá:ka, and Mohawk on which the Summer Institute takes place.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in