The Essential Diagnostics List: bridging the gap between device and diagnosis

Published in Microbiology

One of the problems of addressing something so broad and monolithic a problem as infrastructural diagnostic capacity, is galvanising political commitment. Could the Essential Diagnostics List provide stewardship for encouraging governments to undertake crucial lab strengthening?

First conceived as an ‘impossible’ idea a year ago at the McGill Summer Institute 2017, the development and establishment of an Essential Diagnostic List (EDL) has been a triumph of advocacy, individual championship, and cross-sectoral commitment. It has the potential, much like its predecessor the Essential Medicines List (EML), of being taken up globally, posing a pivotal moment for diagnosis in Global Health. But its creators are quick to point out that impact will only be seen as individual countries take up its mission, as Professor Pai rounded up on the last day of the course, getting the EDL published is just the start of the process, not the end;

“What do we even care about? It’s not the list at end of the day, it is getting our patients access to the test that they need. […] You can’t just have a list of tests. Where are your labs? Where are your people? Where is your supply chain?”

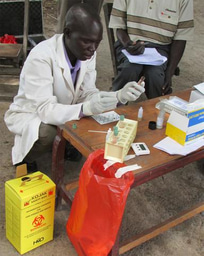

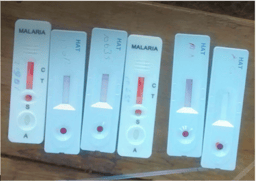

India has been the first country to lead the way in this process, first meeting in Delhi in March 2018, and due to meet again later this year. As findings from Kohli et al.’s survey assessing the availability of diagnostic facilities illustrated in Prof Pai's presentation on the EDL, healthcare is a ‘state subject’ in India with tremendous variation across the country. This in part may explain why the swift response to the Nipah virus outbreak in Kerala state was so effective, compared to the capacity mapped in many northern states. Recognising the need for a regionally adapted application of the EDL, stakeholders in India have agreed on the need for the list, but further advocated a state specific list (Dr Kamini Walia, Indian Council of Medical Research). In the long-term, regionally adapted versions of the list could spur state and district level investment in laboratory infrastructure needed to bridge the systems-technology gap created in part by the global shift and over-emphasis on point of care testing. “If we all believe that we want to get here in all LMICs, that’s a heck of a lot of work to do. My hope is that the EDL will inspire us to go back and reinvest in laboratories.” (Prof Madhukar Pai). In doing so it could also bridge another gap, that between device development and scale up, by promoting systems strengthening and laboratory training across primary and tertiary healthcare levels.

All eyes are now on the EDL as a tool for overcoming some of the divisions between technologies and systems, and the dichotomy between point of care testing and centralised laboratories discussed throughout the week in Montreal. While the true scale of its impact is yet to be realised, the Essential Diagnostics Lists could unify the global healthy community around a common purpose; galvanising country-level political commitment to raising access to diagnostics on the public health agenda. The first edition of the EDL has not been immune to the trade-off between generalisability versus local relevance itself, with no differentiation between which tests, for TB for example, are ‘more essential than others’. How future versions of the EDL evolve as it is taken up and adapted by individual countries remains to be seen, but with research communities already approaching to have their diseases and devices added to the list, the potential for the EDL to transform the landscape of global health diagnostics is profound, and sure to stimulate much debate over future Summer Institutes to come.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 715450.

The author would like to thank Professor Madhukar Pai and Dr Alice Street for their helpful comments and input on this series. The author acknowledges the lands of the Abenaki/Abénaquis, Haudenosauneega, Huron-Wendat, Kanien'kehá:ka, and Mohawk on which the Summer Institute takes place.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in