Reimagining point of care testing and the role of the central laboratory

Published in Microbiology

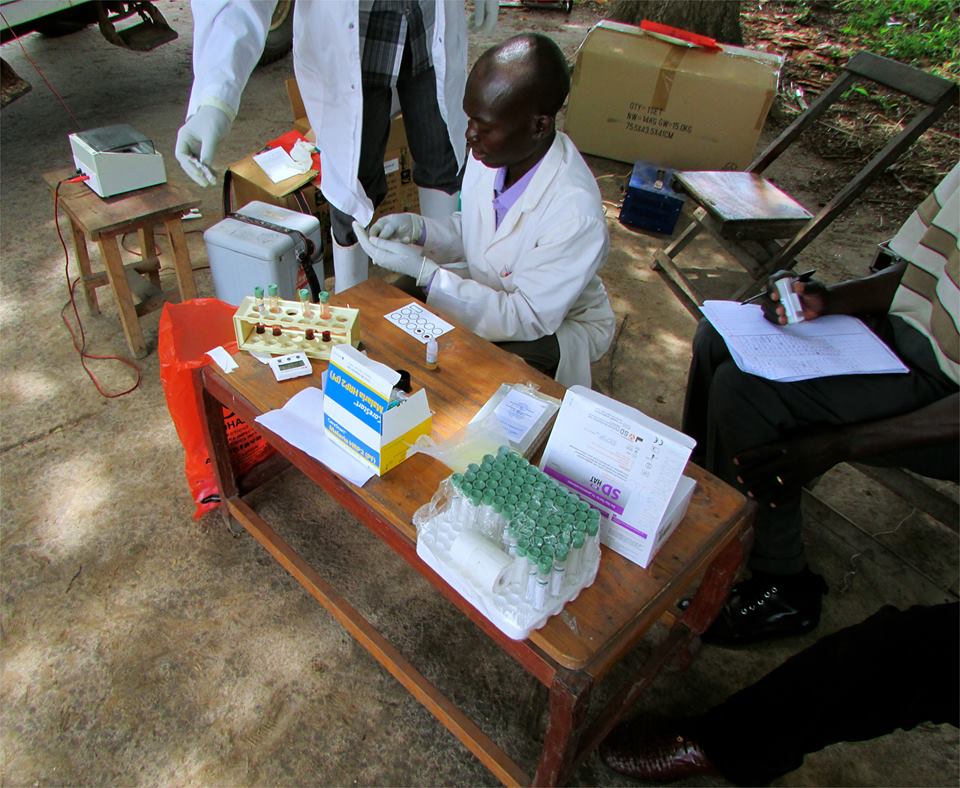

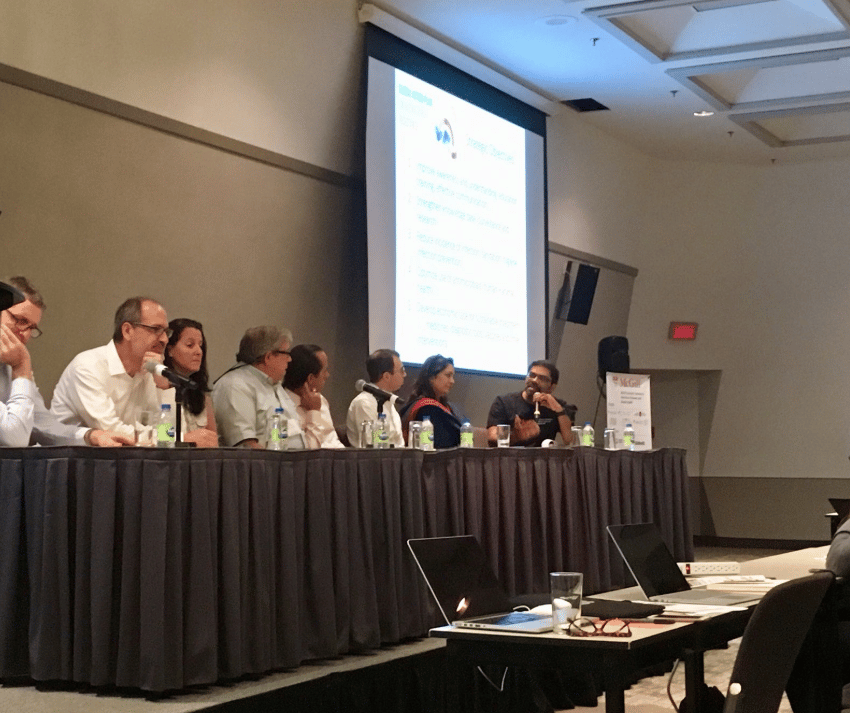

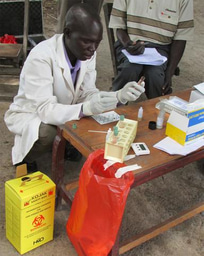

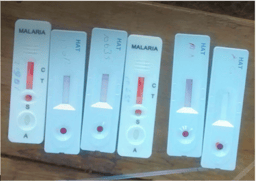

For years, funders and policy makers have been making the case for the development of point-of-care tests that can work in places without laboratory infrastructure. Access was often prioritised over accuracy in these debates. But one of the most striking common themes to run through the presentations at McGill was the recognition of the continued importance of and need for investment in effective centralised laboratory infrastructure in low and middle income countries. Any focus on rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) or disease specific solutions were more often seated within discussions surrounding their position within a wider assemblage of socio-technical ecosystems.

While there is such a wide spectrum of diagnostic settings in which we can aim to implement a test, diagnostic laboratory capacity as a whole is crucial. Specific tests are important, however it is unlikely that the benefits of point-of-care testing can be realised until the ‘backbone’ of laboratory and clinical networks have been integrated, and the ecosystem is ready to receive them. Again, this comes down to a question of who is going to pay for the system. As course co-director Cédric Yansouni put it, “many funders are not willing to fund health systems strengthening. It’s a profoundly unsexy topic and yet what is needed across the board”. Elsewhere, Steve Badman from the Kirby Institute at the University of New South Wales took up the same point on the role of funders and governance in contributing these mind-sets. “One risk is there is lot of emphasis on point of care diagnostics and their role […] I'm concerned about the degree that's reflecting away from other clinical tests that are at risk of being lost in the discussion”.

During a panel on the current and future role of the centralised laboratory, Prof. Madhukar Pai honed in on the underlying political and cultural environments in the global health community which have co-produced the landscape we find ourselves in today; “This fixation on point of care thinking has come at the cost of developing lab capacity, and we have to reject this mind-set that poor people have to make do with these cheap point of care tests without investing in proper care. I don't think there’s any question about whether we need laboratories, the question is how can we get the global health community to drop that old mind-set [...] "I think we have to stop thinking of finding an easy solution and accept that it is hard work”. The narrative that poor countries ought to simply innovate their way out of poverty in Development circles has no doubt shaped the way the Global Health community has come to expect LMICs to circumvent infrastructural gaps by innovating around them with stripped down, cheap devices. Rapid point of care tests are the epitome of this curve toward frugal innovation. However, as these conversations at the summer institute highlighted, it may be time to rethink Global Health infrastructures that prioritise cheap point of care tests over investing in structural systems and central laboratory networks.

The language we use in creating these narratives is important, shaping how we frame problems and their solutions. For example, both Pai and Badman referred to the perception of the central lab as a “black hole”, contributing to a reluctance by clinicians to rely on them, or governments to invest in them, urging a careful re-framing of the issue and use of the EDL as a galvanising tool of advocacy; “We need to be careful about how we define what a central lab is. The language we use to describe centralised labs vs point of care with a hole in the middle is a language we need to reframe, so we can think about its functions and as something that we can be supporting” (Steve Badman).

The crux of the issue was epitomised during a panel on diagnostics for antimicrobial resistance, after Dr Makeda Semret commented that, while labs and trained staff were once commonplace in many LMICs before HIV, the move to single disease testing ‘destroyed’ the central lab. However, as Mark Miller from bioMérieux pointed out, the climate created by global health agendas and donor missions limited the scope for industry to explore central lab strengthening; “The impact has been done by influential groups saying we need to do point of care, but not lab testing. So companies like us have had to de-invest in building lab infrastructures because it’s all RDTs, point of care, ‘in the bush’ diagnostics. So now we're going back to regional labs, and people are coming to us saying ‘so where are your [lab] tests?’ Well we de-invested in these tests because you told us to focus on RDTs!” One audience member then responded and countered the point, asking “So did HIV kill the lab, or did [the donors] kill the lab?”

Much emphasis has been placed on developing high end technologies, but many participants and speakers raised concerns about how PoC testing and RDTs have come at expense of investing in central labs, and so many concluded we should be focussing efforts on capitalising on what we already have and improving basic infrastructure. “In the digital age we always want the 'next generation', but I think we should make the best out of what we have” said Emmanuel Fajardo, HIV/HCV diagnostics advisor for Medécins Sans Frontièrs. Dr Kamini Walia concluded that “the question should be, should we wait for new tests or strengthen our capabilities that we already have? I would go with second option.” Even for one disease where we are talking about a single tool, there are myriad issues that need to be addressed to optimise it.

Systematically focussing on RDTs has pushed investments in lab support to the margins. Even in 2018, cheap point of care tests continue to be framed as the solution for all low and middle income countries. We still think labs are too expensive, difficult and impossible to invest in, consequently pushing the issue into the future. If the conversations spurred from this week have signalled anything, it is that the mind-set in the global health community that LMICs should ‘put up with RDTs’ needs to change, and technical innovations around critical gaps in infrastructure are no longer acceptable as sufficient for meeting diagnostic needs in poor countries. “Poor countries deserve good laboratories, and point of care devices too. All countries deserve the technologies that we enjoy here. It is time to reject the mind-set that RDTs and syndromic treatments are adequate for poor countries, and work towards having a functional lab infrastructure” (Prof Madhukar Pai).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 715450.

The author would like to thank Professor Madhukar Pai and Dr Alice Street for their helpful comments and input on this series. The author acknowledges the lands of the Abenaki/Abénaquis, Haudenosauneega, Huron-Wendat, Kanien'kehá:ka, and Mohawk on which the Summer Institute takes place.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Somehow, I have also never understood the undue importance which is being accorded to PoC tests. Developing POC tests for each and every etiology in a clinical microbiology lab itself would be a stupendous task. But, at the same time, somehow I do not feel like accepting that too much emphasis on PoC testing is depriving the laboratories of the funds/investments. I think these issues need a larger debate. Nevertheless we do need to de-glamorize the PoC testing a bit.

Thank you for your comment . I absolutely agree that this is a complex issue that warrants deeper debate than my post offers, and I hope that this piece can be read as a part of a wider discussion that is taking place among the global health community on how much emphasis is placed on discrete point of care tests. Whether this happens at the expense of investing in centralised laboratory capacity seems to depend on regional priorities, and I'm sure isn't the same across all disease programmes. You are right that perhaps I have framed the issue too broadly and failed to take these local nuances into account. I would be keen to learn more about how this is viewed from the standpoint of specific countries, and how decisions on diagnostic investment are informed at this level. The issues raised throughout the course at McGill by those in the business of developing diagnostic devices seem to suggest that an over-emphasis on PoC in the global diagnostic agenda has deterred funders from investing in core lab infrastructures, and nudged investment toward simple, single-disease solutions. However this doesn't necessarily apply to how countries themselves prioritise diagnostics strategies, and perhaps there are lessons to be learned from how infrastructure is either augmented or excluded by PoC devices across different settings.