Acquisition of tolerance to blue light toxicity via microbiome-mediated obesity

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Microbiology

Evolutionary potential extended by the microbiome and its experimental validation

Understanding rapid evolutionary processes, such as the acquisition of tolerance, is crucial — and they are fascinating. Organisms may not evolve in isolation; their associated microbiota can contribute to adaptive potential, extending evolution beyond the host genome (1). In this context, microbiome-mediated evolutionary adaptations have attracted increasing attention. For instance, specific bacterial species can be closely associated with host adaptive phenotypes, resulting in an increased relative abundance of these bacteria and a concurrent reduction in microbial diversity (2). Approaches such as laboratory selection and experimental evolution are powerful means of uncovering such processes in evolutionary studies.

Unexpected discovery: Blue light tolerance in fruit flies is linked to microbiota-mediated obesity

The toxicity of blue light induced by excessive exposure in insects has attracted attention for its medical relevance and as a potential alternative to chemical pesticides for pest control. However, its practical application is currently limited due to the delayed onset of toxic effects. This highlights the need for a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms and the development of strategies to improve its effectiveness in pest management.

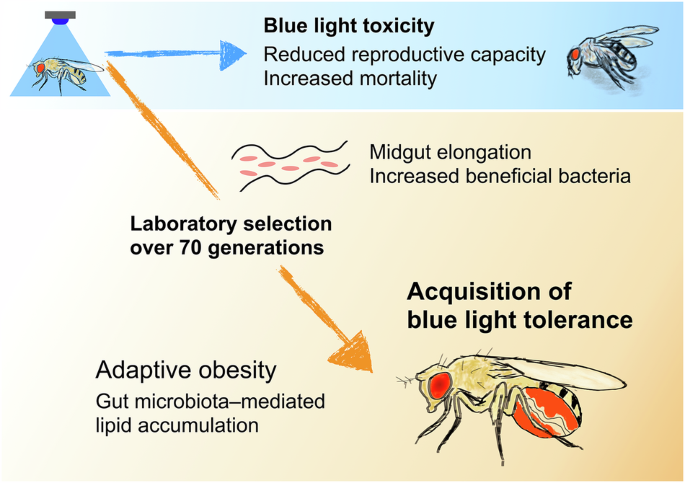

To investigate the evolutionary response to this toxicity, we conducted laboratory selection experiments using Drosophila melanogaster, exposing the flies to blue light for over four and a half years (more than 70 generations). Through this long-term selection process, we successfully established fly strains that had acquired tolerance to blue light toxicity, and unexpectedly found that this tolerance depends on obesity induced by the gut microbiota (3).

First, we found that the tolerant flies exhibited an obese phenotype. Further analysis revealed that this obesity was mediated by the microbiome. The tolerant flies had an enlarged gut and a significantly higher abundance of acetic acid bacteria (Acetobacter). When treated with antibiotics, the tolerant flies lost their obesity and blue light tolerance phenotypes, while retaining their enlarged gut. Genomic analysis of the tolerant flies revealed variants in genes associated with organ size regulation, suggesting genetic changes driven by selection. Notably, we also identified variants in Tachykinin, a neuropeptide known to regulate lipid metabolism through host–microbe interactions (4). Transcriptomic profiling and genetic manipulation provided further support for the hypothesis that altered Tachykinin expression plays a key role in acquiring blue light tolerance.

We also observed a broad downregulation of genes associated with mitochondrial metabolism in the tolerant flies. Mitochondria are known to be a major target of blue light toxicity, which has severe consequences for energy metabolism, including ATP production (5). One possible explanation for the adaptation involving microbiota-dependent obesity is that the host can secure energy more efficiently by delegating certain aspects of lipid metabolism to the gut microbiota.

Maximise the microbiome through host evolution.

Together, our findings suggest a model in which host evolution is shaped to maximise the benefits of the microbiome, driving adaptation through genetic changes and an increase in bacterial abundance.

At the outset, we did not anticipate that gut microbes would play such a central role in the flies’ adaptation. Following microbiome-driven evolution across generations may, in the future, reveal fresh insights into how adaptation unfolds in complex host–microbe systems. Importantly, studies in the fields of evolution, physiology and neurobiology highlight Tachykinin-mediated lipid metabolism as a key component of the Drosophila–Acetobacter interaction (4, 6). Looking ahead, focusing on these processes in experimental evolution studies with Drosophila could provide new insights into the potential of host evolution.

For more details, please refer to Takada et al., 2025, Communications Biology

References

(1) Henry, L. P., Bruijning, M., Forsberg, S. K. G. & Ayroles, J. F. The microbiome extends host evolutionary potential. Nat. Commun. 12, 5141 (2021). doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25315-x

(2) Henry, L. P. & Ayroles, J. F. Meta-analysis suggests the microbiome responds to evolve and resequence experiments in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Microbiol. 21, 108 (2021). doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02168-4

(3) Takada, Y., Ichinose, T., Fuse, N., Saito, K., Ikeda-Ohtsubo, W., Tanimoto, H., Hori, M. Gut microbiota-mediated lipid accumulation as a driver of evolutionary adaptation to blue light toxicity in Drosophila. Commun. Biol. 8, 998 (2025). doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-08348-6

(4) Jugder, B. E., Kamareddine, L. & Watnick, P. I. Microbiota-derived acetate activates intestinal innate immunity via the Tip60 histone acetyltransferase complex. Immunity 54, 1683-1697.e3 (2021). doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.05.017

(5) Yang, J., Yujuan, S., Kumar, R., Sundaram, S., Ramsell, B., Di, Y., Giebultowicz, J. & Hendrix, D.A. Transcriptomic profiling of eyeless Drosophila reveals molecular network orchestrating response to blue light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 271, 113225 (2025). doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2025.113225.

(6) Marcu, D., Sannino, D.R., Dornan, A.J., Ibrahim, R., Kapoor, A., Wood, M. & Dobson, A.J. Microbiota/gut/neuron axis promotes Drosophila ageing via Acetobacter, Tachykinin, and TkR99D. bioRxiv (2025) preprint doi: 10.1101/2025.07.31.667994 (Accessed 6 Sept 2025).

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in