Onset of Benguela Upwelling influenced climate and triggered desertification of southern Africa

Published in Earth & Environment

The story begins with a Boundary Current driving upwelling

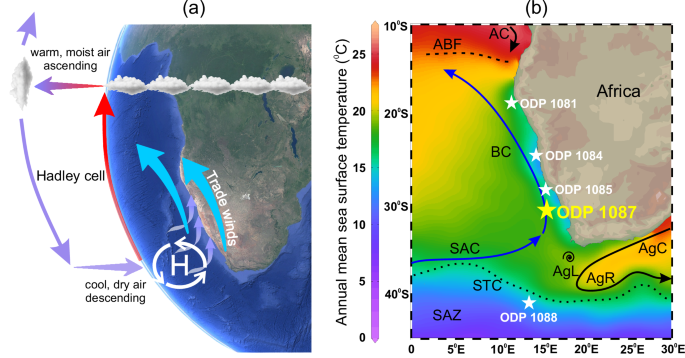

Boundary currents not only are critical in surface ocean circulation, transporting surface waters between tropics and poles, but also in influencing continental climates. The vigour of these surface coastal currents impact strength of upwelling cells, and consequently wetting and aridification of the adjacent landmasses. For instance, the Benguela Current drives upwelling along SW Africa and the Benguela Upwelling System (BUS) has driven the expansion of the Namibian desert since the late Miocene. The BUS is one of the most productive marine regions in the world ocean. It carries cold and nutrient-rich waters that sustain booming ecosystems, and influence the hinterland climate and habitability of southern Africa.

When we first launched this study, one question intrigued us deeply: Could the intensification of this upwelling have triggered the expansion of deserts across southern Africa millions of years ago?

That question guided our years of careful analysis and interpretation, and ultimately, the story emerged from planktic foraminifera, which are tiny, floating, single-celled calcareous marine protists whose shells are preserved in ocean bottom sediments.

From the seafloor to the microscope

Our work focused on marine sediment samples recovered from Ocean Drilling Program Site 1087C (Leg 175), a 492 meter-long core located off the southwestern coast of Africa. These sediments preserve nearly twelve million years (12 Ma) of ocean and climate history. Within these sediments are found fossil planktic foraminifera, the main story-teller in this study. These zooplanktons live in the upper layers (top ~ 200 m) of the ocean water column, and build delicate shells of calcium carbonate that incorporate the chemistry of the ambient waters.

The planktic foraminiferal assemblages reflect changes in sea surface temperatures, nutrient availability, strength of cold-water upwelling and surface-water properties. All these make them one of the most reliable proxies for reconstructing past oceanographic and climatic conditions.

Identifying and counting the 30 most common foraminifera species is tedious and tiring but rewarding. We analysed more than 500 sediment samples, each one containing more than 300 individual specimens of planktic foraminifera, with patience and precision. We interpret intervals with cooler-water species as periods of strong upwelling, while those with warmer-water species indicate times of weaker upwelling or greater influence from warm Indian Ocean waters, advected around the tip of south Africa by the Agulhas Current.

In addition to population analysis, the stable oxygen and carbon isotope ratios of the foraminifera shells were analysed on a Thermo Scientific MAT 253 Plus mass spectrometer at Brown University, USA. The isotope data supported our faunal results and gave us independent evidence for temperature, productivity, and changes in water mass sources.

A long view of climate: 11.7 million years to today

Our findings provide a continuous reconstruction of the BUS from ~11.7 Ma to the Present.

The results were striking. About 10 million years ago (Ma), the Southeast Atlantic was dominated by the warm Agulhas waters flowing in from the Indian Ocean. However, at ~ 9.8 Ma, this balance shifted. Strengthened trade winds began driving cold, nutrient-rich waters to the surface, thus triggering the onset of the Benguela Upwelling System.

Cooling during the Late Miocene between ~8.0 and 4.8 Ma, further intensified this process. Increased upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water both enhanced primary productivity and stabilized the atmosphere, as well as suppressed rainfall over the coastal regions of the continent. This cooling and drying trend triggered and amplified aridification across southern Africa; a turning point in the climatic transformation that ultimately shaped the region’s landscapes and ecosystems.

Later, between about 4.8 and 3.7 million years ago, the system went through an unusual warm phase. Warm conditions in the early Pliocene caused a break in the link between upwelling and aridification. During this time, the warm Angola Current moved farther south, creating Benguela Niño–like conditions, which are similar to modern El Niño events that temporarily weaken the upwelling. As the global climate began to cool in the Plio-Pleistocene, the upwelling strengthened once again, contributing to rapid aridification.

In short, our study showed that the Benguela Upwelling System did not simply react to global climate changes; rather, it acted as a driver to those shifts, controlling the timing and strength of southern African aridification.

Moments of struggle and discovery

The most challenging part of this work was, without doubt, counting the planktic foraminifera. Each of the hundreds of samples contained thousands of tiny fossils, and sorting them took years of careful effort. As the data came together, clear patterns began to appear, and every long hour at the microscope suddenly felt worth it. When we plotted the first complete oxygen and carbon stable isotope records alongside the foraminiferal data, the connection between stronger upwelling and continental aridification was unmistakable. For the first time, the results told a continuous story linking the ocean, the winds, and the gradual drying of southern Africa.

Why it matters

Our study examines not only the history of a specific upwelling system, but presents a larger idea: that Boundary Currents can affect climate and life on the continents. With global warming continuing to impact our oceans and atmosphere, the lessons from the Miocene and the Pliocene epochs are prophetic. The BUS, like all upwelling systems, is an important indicator of the balance of Earth's climate, highlighting that even local shifts in the ocean have extensive impacts on the continental climates.

Looking back

What began as a simple curiosity about deserts and ocean upwelling turned into a long journey of unveiling how the climate on land has changed over millions of years. Working between the microscope and the story of the global ocean, we were often flabbergasted by how these beautiful, minute creatures could reveal such an interesting story, a story that still lives on in the winds and waters along the Namibian coast today.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in