People overlook subtractive solutions to mental health problems

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

The algorithms that feed my timeline have concluded that I’m a man and that I’m interested in mental health. Naturally, this means that content created by Andrew Huberman and other such people feature prominently in it. I’ve long been curious about the advice being peddled in this content. Putting aside for a moment their tendency to offer advice based on limited evidence, one other thing that’s also struck me is that the amount of advice being offered never stops. Apparently, to feel better you need more sleep, more exercise, healthier food, a meditative practice, a plunge pool, a testosterone supplement, the list is endless. I’ve wondered how this might seem to someone who is really struggling with their mental health and not just someone in search of the latest hacks to optimise their lifestyle.

Surely, these videos would imply (correctly) that managing your mental health is pretty complex and involves lots of different factors and considerations. Perhaps also, however, they imply that managing your mental health requires such effort – through all of the necessary changes to your sleep, diet, exercise, relationships, media consumption etc. – that having good mental health is insurmountably difficult. Perhaps the people for whom this burden is felt most strongly are those most in need of guidance and change and those who feel least capable of creating that change.

While thinking this, I saw a paper in 2021 by Gabrielle Adams and colleagues (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03380-y) about the tendency of people to overlook subtractive changes to problems that they encounter in many domains in life, from basic geometrical problems to problems involving large corporate entities. I wondered whether we approach mental health problems in the same way. In particular, I wondered whether there is a tendency (not just by Andrew Huberman et al.) to offer mental health advice that is disproportionately additive in nature (e.g., take up yoga, meditate, walk 10,000 steps, see a therapist etc.) and where subtractive solutions (e.g., cut out junk food, bad relationships, smoking, gambling etc.) are overlooked.

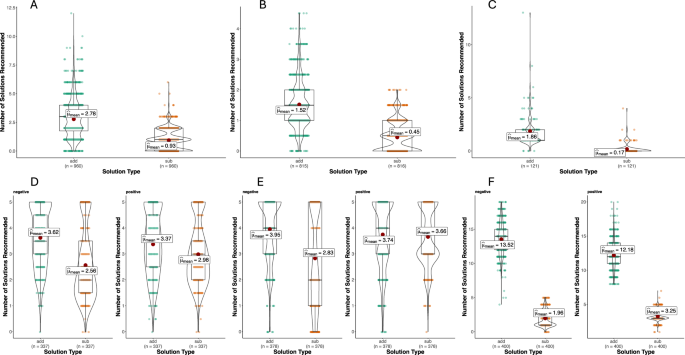

This is indeed what we found. People are overwhelmingly additive, even when we designed our experiments to encourage them to be more subtractive. This was also the case outside of artificial, experimental settings, as we found the same pattern of advice-giving on Reddit. Since many people these days are also asking generative AI models such as ChatGPT for advice, we also analysed the advice it gave. Unsurprisingly – given the data from our online interactions with one another that it’s likely been trained on – GPT 4o was also overwhelmingly additive.

Part of this bias appears to be explained by a belief that additive advice is easier to implement and more beneficial than subtractive advice. Interestingly, the only space in which subtractive solutions were considered to be more beneficial than additive solutions was when we asked participants to advise a close friend. Apparently, it’s easier for friends to cut things out than it is for us to do it ourselves.

Although there is much still to do in this area to explore my assumptions about how this additive bias might ultimately burden the most vulnerable of us, we have at least begun to shine a light on how non-experts advise one another and the overwhelming tendency that we all have to tell people to do more. Perhaps once this article has been digested by the systems that feed my timeline, it will recommend that I subtract videos about Andrew Huberman from my life.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Psychology

An open-access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary. The scope of the journal includes all of the psychological sciences.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Intensive Longitudinal Designs in Psychology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Replication and generalization

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in